Interview by Christina Simmons

Erica Ryan’s Red War on the Family (Temple 2014) argues that the first Red Scare–the backlash against and anxiety about domestic and foreign radicals–and its organizational progeny not only deeply shaped the American political world of the 1920s but also fundamentally affected ideas and practices of sexuality and gender, marginalizing feminists and sex radicals. Ryan analyzes the rhetoric of antiradicals who assailed the left (“Bolshevism”) by counterposing an “Americanism” which they built in large part on a conservative patriarchal vision of sex, gender, and marriage. She traces battles of post-suffrage feminists and antifeminists, efforts to reinforce masculine authority through a homeownership campaign, Americanization programs run by the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) and others by settlement house progressives, including fascinating early sex education classes, and popular debates about the “marriage crisis” and companionate marriage. She demonstrates the interplay and overlap of antiradicalism, antimodernism, and antifeminism as forces that pervasively connected the realm of the intimate and familial with the arena of formal political activity, tightly linking the personal and the political. In this she suggests that 1920s conservatism foreshadowed the New Right’s use of sex and gender as an organizing tool since the 1970s.

Christina Simmons: You focus your study on the rhetoric and conceptual framework of Americanism, especially the part centered on sex and gender. Obviously, we can never really separate the discursive and the material, but could you reflect on what social forces allowed this conservative discourse about family to carry so much weight? What were the material sources of power for these views? Was familial rhetoric more effective than formal capitalist economic ideology when appealing to ordinary men? In a culture already imbued with reverence for the family, were these popular responses as important as economic and political power, in making the sex and gender aspects of Americanism so salient and so culturally formative?

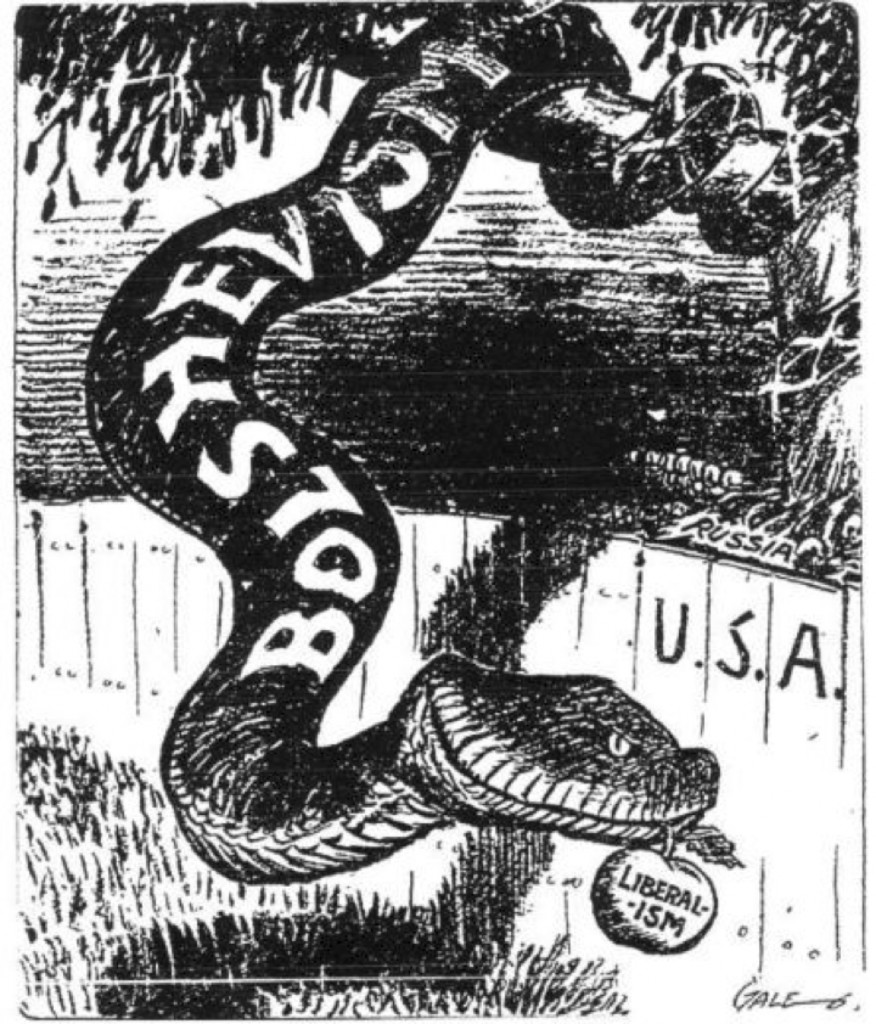

Erica Ryan: American conservatives responded to the Russian Revolution abroad and upheavals at home by advancing a self-consciously gendered and sexualized politics that they called “Americanism.” These conservatives enacted social programs and a cultural agenda that sought to stymie domestic radicalism and blunt the impact of feminism and sexual modernism, and they did so using language that fused family and patriotism. If we think of heterosexuality as a modern social and political system established in the 1920s, then analyzing conservative activism during the first Red Scare gives us insight into the institutions and actors that helped lay its groundwork.

Americanism shaped the culture of this era because of the sheer complexity of the conservative consensus, because it managed to encapsulate economic and political concerns even as it focused the local and intimate anxieties of a more popular audience. The social forces animating this movement were numerous. In addition to Red Scare antiradicalism, Americans struggled with nativism against immigrants, the fight over internationalism and the League of Nations, the dislocations and conflicts of the Great Migration, a tidal wave of labor unrest involving more American workers than ever before, the arrival of modernism in American culture, a veritable moral revolt among middle class youth, a growing birth control movement, and of course, the suffrage victory for women. In bearing the impact of these social forces, I do think Americans wished to embrace something that seemed stable, and familiar. Popular contributions to Americanism developed in part out of this desire. Both these popular responses and top-down influences carried the movement forward, giving it substance, so both were equally important.

At heart, this book argues that the salience of the antiradical argument depended on those ordinary men seeking authority in the family. It was the very use of sexuality and gender in configuring antiradicalism that made disparate and confused issues seem cohesive, enabling the widespread acceptance of conservative ideas in the 1920s. Ultimately, this facilitated the maintenance of a range of conservative social and political conventions that may seem distant from discussions about sex and gender.

CS: Do you have any reflections on how important ordinary people’s familial and sexual lives actually were (as conservatives believed) to “social stability”? In other words, were the conservatives right in a way–or at least smart!–to make these connections?

ER: I do think conservatives were smart to make these connections, for a few reasons. While radicals in the 1920s employed urgency and fiery rhetoric, conservatism struck many as more passive. By linking political conservatism to a notion of moral emergency, conservatives fostered powerful links between social stability, gender and family norms, and the political status quo. Also, American fears about family stability were not new in the 1920s. But in this decade conservatives crystallized an antiradical political ideology, one where an apparent family crisis reflected larger political, economic, and social concerns. Stable, heterosexual, cohesive families with breadwinner fathers at the head would, many conservatives felt, maintain a vulnerable moral and political order. The conservative position in the 1920s—and again in the second half of the twentieth century—charged families rather than sound social policies with the tasks of minimizing childhood poverty, assimilating maladjusted individuals, containing labor unrest, lowering crime, and tamping down social and political discord. We still see this position in American political culture today.

CS: Nancy Cott argues in Public Vows that in the nineteenth century marriage served as a form of governance for a (white) population spread out across a vast country with as yet few established governmental institutions. By the early twentieth century society needed marriage less for that purpose, and, she argues, the overt connection of “monogamous morality to political virtue” declined, and the state “concentrated more on enforcing [marriage’s] economic usefulness.” You make a strong case that, at least for proponents of Americanism, the link between monogamous patriarchal marriage and political virtue remained strong. Should we see the proponents of Americanism as fighting a rearguard popular action, while the state (in some ways at least) moved on to less strictly moral approaches?

ER: The shift Nancy Cott describes provides a crucial backdrop for the story I tell in this book. As society began to need marriage less as a form of governance, sexual modernism permeated middle class culture. And, with the Russian Revolution, Americans began to see communism as a threat to family life, to marriage, and to morals. Americanism served in part as a backlash to all of these developments in a charged political culture.

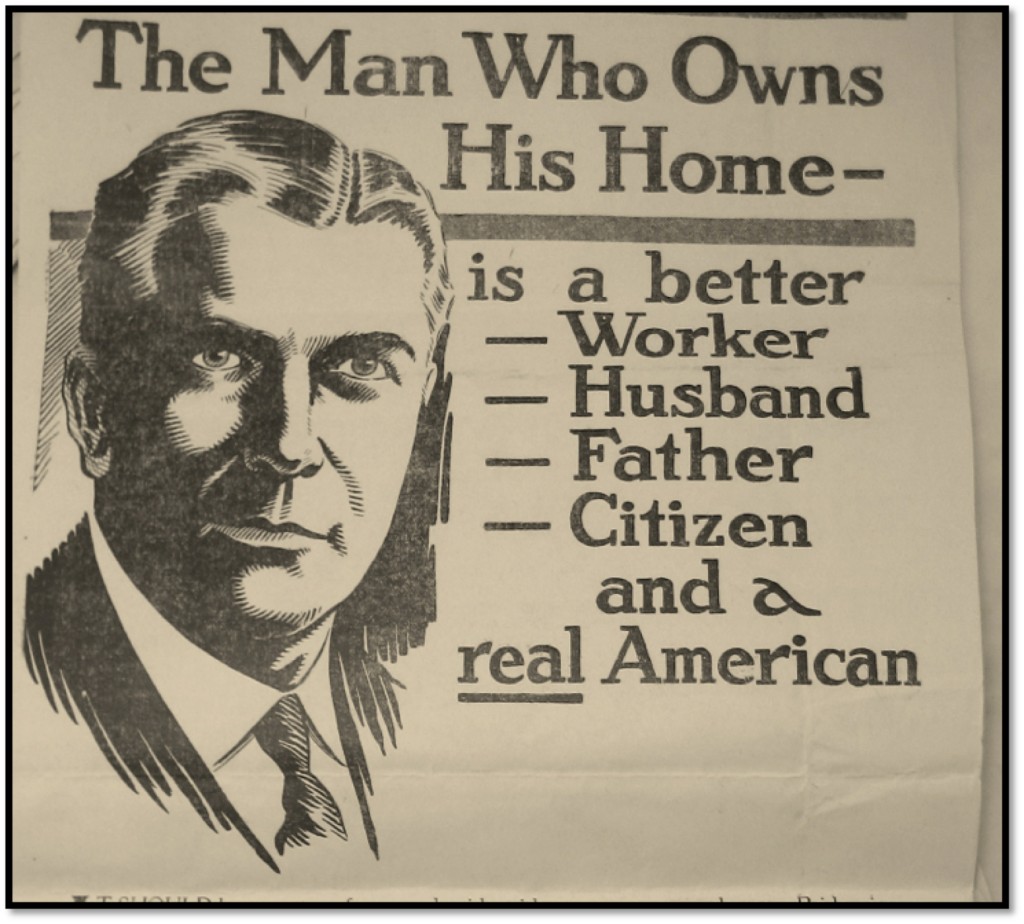

I do think we can situate proponents of Americanism as players in a rearguard popular action against the shifting public framework of marriage, something that was well underway by 1919. But it wasn’t only coming from popular actions. It is worth noting that one of the government agencies directly implicated in the development of this brand of Americanism, the Department of Labor, did similar work with their Own Your Own Home campaign. This national effort to boost home ownership amongst working class men positioned monogamous marriage and family life very purposefully as bulwarks against Bolshevism in both moral and economic terms.

In 1920, when women won the right to vote, conservatives responded by vaunting the political role of women as wives and mothers defending the hearth and home from the evils of Bolshevism. These proponents of Americanism directly sought to limit the liberatory potential of the suffrage win. They crafted and publicized—in the name of national defense—a restrictive citizenship role for women. And by the late 1920s, many feminists, including Democratic committeewoman Emily Newell Blair, wondered aloud about women’s apparent failure to impact the world of politics after 1920. We can attribute this “failure” to several things, including the very significant breakdown in organized feminism, and the antiradical attack on activist women. But this book argues that it was also due to the way Americanism framed women’s place politically as within the confines of monogamous marriage and motherhood. In so doing, conservatives self-consciously advanced a gendered and sexualized political worldview under the banner of Americanism. They sought to stem the tide of change by boosting this sexualized and gendered Americanism, and in the process they blunted the real impact of the suffrage win.

CS: I wonder about the difference between antiradicals like the Daughters of the American Revolution and progressive settlement workers. The former’s programs seemed to address how to run a household–styles of cooking or means of hygiene whereas the settlement workers actually took up gender and sexuality concerns more, as in the Young Women Christian Association’s International Institute’s commission to study second-generation girls or the United Neighborhood Houses’ intriguing 1927 sex education programs, which included some very liberal and even radical readings. Did the DAR focus on household work because it found many immigrant families actually conservative enough already on sex and gender? The settlement workers, on the other hand, wanted to convey more liberal attitudes, especially on gender, even though they also hoped to confirm marriage as the appropriate way to organize personal life. Were the antiradicals and the settlement workers really doing the same things?

ER: This tension between conservative reformers and the progressives was a surprising development in my Americanization research. While I thought their approaches and intentions would be quite different, it seemed important to me to acknowledge that in fact, both the Daughters of the American Revolution and progressive groups like the International Institutes and the United Neighborhood Houses sought to create orderly American bodies, that their efforts at heart were projects of cultural conformity in support of the developing social structure of heterosexuality. But, within that effort, as you point out, they were not doing the same things. And that is true in two significant ways.

First, they had vastly different views on the conflict between old world culture and new world culture. Conservatives like the Daughters of the American Revolution sought to impose what they saw as a superior American culture upon immigrants. Progressive reformers firmly committed themselves to the prospect of blending old and new world cultures. As proponents of the cultural gifts movement, many progressives celebrated old world customs even as they helped immigrants develop an appreciation for those of the new world.

Second, and perhaps more significantly here, these groups employed different frameworks for reform. The Daughters of the American Revolution’s efforts were focused on creating homogeneity within the material culture of the home, throwing over old world foods, hygiene practices, and homemaking styles in favor of American ones. And as you noted, they may not have gone further because they were satisfied with the family structures they encountered in immigrant households. But however conservative immigrant families appeared to be on issues of sex and gender, immigrant daughters served by the DAR undoubtedly struggled with shifting sex and gender norms, with the clash between a modernizing American culture and their old world influenced homes. And progressive reformers built a framework for reform around this reality. Leaders in the United Neighborhood Houses recognized the unique alienation of the “second generation girl” in 1920s America, and worried that a morally rudderless immigrant youth might completely devalue marriage and family life. They acknowledged the role sexual modernism might play in young people’s assimilation—that point needs to be made.

Yet, in this decade where heterosexuality was being established, I was struck by the fact that both conservatives and progressives fostered a different-sex, monogamous, marital model as the only desirable way to organize personal life. The Americanization effort was in many ways about solidifying popular understanding of American ideals, and heterosexuality as a social system was one of them.

CS: In your final chapter you document how antiradicals attacked women reformers, rebellious youth, and marriage reformers as abnormal and/or as Bolsheviks. On example was the famous Judge Ben B. Lindsey, proponent of companionate marriage. Your research adds a useful perspective on the story told by historian Rebecca Davis about the intense hostility to Lindsey and his ideas in the 1920s–you show the attacks on Lindsey as part of the wider antiradical campaign. But why did the conservatives focus on him rather than people with more anti-marriage agendas?

ER: This is a compelling question, and one that challenged me in my research for the book. I anticipated many direct attacks on sex radicals like V.F. Calverton, a reformer, author and editor from the Old Left, but I did not find them, despite the fact that he celebrated the idea of ending monogamous marriage. Calverton overtly applauded Soviet policies as models of a better way, for example, in relation to illegitimacy laws. In an essay collection he co-edited on the “intimate problems of modern parents and children,” he exposed the hypocrisy of capitalism’s influence in determining the status of children as legitimate or illegitimate. “Life acquires value not because of its life, but because it is connected with the matter of property and its transmission,” he argued. “The illegitimate child is scorned, and the unmarried mother stigmatized, because they are a menace to our social order. They strike at the economic foundation of our whole system of morals and marriage.” “In Soviet Russia,” Calverton was quick to point out, “there are no illegitimate children.”

So, given this radical challenge to capitalist and marriage ideals embedded in Americanism, why did antiradicals instead go after Lindsey, whose “companionate marriage” scheme in many ways served only to reinforce monogamous marriage? There are a few things to consider. Lindsey’s support for birth control within companionate marriage was indeed still “radical,” and polemical. Lindsey’s book became a symbol for the sweeping concerns many Americans felt about youth culture, the “marriage crisis”, and radicalism more broadly. The press covered The Companionate Marriage and its contents constantly. Lindsey was well known, certainly more widely known than Calverton and his peers, and when antiradicals attacked Lindsey, it was intelligible to a broader swath of the American public. Conservatives considered him as perhaps a more legitimate (and more worthwhile) target because he proposed a model based entirely in reality. The sexual and social order promoted by Calverton seemed fantastical to many, yet Lindsey called for reforms rooted in changing realities. And indeed, by linking those real changes to Bolshevism, antiradicals hoped to discredit them.

We can read these reactions to Lindsey as part of a sweeping impulse toward reaction in the 1920s. The conservative consensus responded to change by touting tradition, both in personal and political terms. Whether they agreed with it or not, by the end of the 1920s many Americans understood that Judge Ben Lindsey’s name reflected fears of radicalism just as much as Vladimir Lenin’s. Popular understandings of Americanism and Bolshevism created in 1919 developed this connection, while a host of influences sustained it: politicians’ pronouncements about the capitalist family, newspaper and magazine articles about the dangers of women and radicalism, the push for homeownership amongst working class men, a range of Americanization efforts focused on the young, and a perceived crisis in marriage and family life.

In this fraught political and cultural moment, long before the New Right advanced a politics steeped in family values, the conservative consensus made gender and sexuality central preoccupations in their construction of 1920s Americanism. Their activism set the stage for subsequent conflicts over feminism, sexuality, family formation, and reproduction. Scholars need to attend to this history because, then and now, this kind of politics prioritizes monogamous, different-sex marriage and stable family life as the cornerstone of national strength. Sometimes plainly, and at other times imperceptibly, this political logic canonizes the patriarchal family as a social unit, marginalizes women as actors in the political arena, and reinforces the power of heterosexuality as a social and political system.

Christina Simmons retired in January 2015 as Professor of History and Women’s Studies at the University of Windsor in Windsor, Ontario. Her 2009 book, Making Marriage Modern: Women’s Sexuality from the Progressive Era to World War II (New York: Oxford University Press), addresses the transformation of the ideology of marriage and women’s sexuality for white and African-American women in the first half of the twentieth century. Her current research focuses on African Americans, sexuality, and marriage education in the 1940s and 1950s.

Christina Simmons retired in January 2015 as Professor of History and Women’s Studies at the University of Windsor in Windsor, Ontario. Her 2009 book, Making Marriage Modern: Women’s Sexuality from the Progressive Era to World War II (New York: Oxford University Press), addresses the transformation of the ideology of marriage and women’s sexuality for white and African-American women in the first half of the twentieth century. Her current research focuses on African Americans, sexuality, and marriage education in the 1940s and 1950s.

Erica Ryan is an Assistant Professor in the History Department at Rider University in New Jersey. She is the author of Red War on the Family: Sex, Gender, and Americanism in the First Red Scare (Temple, 2014). She is in the beginning stages of two new projects: one examines fatherhood in 1990s American political culture, and the other links contemporary American “culture wars” to the political, social, and cultural divides of the 1920s.

Erica Ryan is an Assistant Professor in the History Department at Rider University in New Jersey. She is the author of Red War on the Family: Sex, Gender, and Americanism in the First Red Scare (Temple, 2014). She is in the beginning stages of two new projects: one examines fatherhood in 1990s American political culture, and the other links contemporary American “culture wars” to the political, social, and cultural divides of the 1920s.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com