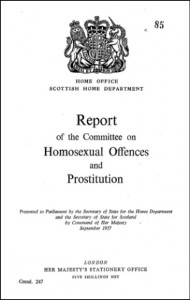

In 1954, the British government reluctantly set up the Departmental Committee on Homosexual Offences and Prostitution (better known as the Wolfenden Committee, after its chairman John Wolfenden) and charged it with the task of investigating the dramatic increase in male homosexual offences known to the police. Three years later, the Wolfenden Report controversially recommended that private homosexual acts between two consenting adults aged twenty-one and over should no longer constitute a criminal offence. The 1967 Sexual Offences Act finally brought these changes into law in England and Wales.

Perhaps most surprisingly, considering recent Anglican conflict over issues of homosexuality, the campaign for homosexual law reform was supported by influential sections of the Church of England throughout the 1950s and 1960s. The Church played a more important role in homosexual law reform than has been previously acknowledged by historians. Certain influential Anglicans encouraged the British government to overcome its initial reluctance to formally consider the existing law on homosexual offences and to include an equivalent examination of this more contentious issue alongside an investigation into the law on prostitution – a problem that government ministers already agreed required the urgent attention of an authoritative inquiry. Anglicans further influenced the shape of the Wolfenden Report’s findings. The submissions of the Church of England Moral Welfare Council (CEMWC) – a body created for the specific purpose of coordinating and extending the Church’s efforts in educational and social work relating to issues of sex, marriage, and the family – anticipated and encouraged the Wolfenden recommendations, arguing “it is not the function of the State and the law to constitute themselves the guardians of private morality… to deal with sin as such belongs to the province of the Church.”

This is clearly an important finding, but its implications need to be addressed carefully. To assume that the Church acted as an agent of permissiveness, or that it had more or less converted to a position of support for homosexual law reform by 1957, is to misinterpret the relationship between the CEMWC and the broader institution it was supposed to represent. The Council’s submissions to Wolfenden (which were drafted by a small number of representatives) did not reflect a consensus of opinion within the CEMWC, let alone the Church of England. The Wolfenden Committee was acutely aware that such views “may be far from representing the views of the churches as a whole… By no means all theologians (and still less laypeople) are so enlightened on these matters.”

The example of the Wolfenden Committee allows us to explore how historians might think about the role of religious authorities and institutions in the making of modern ideas about sexuality. Above all, it must be emphasised that there is no singular or unified Church policy or set of religious attitudes on sex to be unproblematically located by the historian. The historical record presents a cacophony of voices, a constant push and pull between different approaches, resulting in a series of unresolved debates full of tensions and ambiguities, and offering solutions deemed wholly satisfactory by very few. While this may come as no surprise to those working within (or on the history of) the Church of England, this issue continues to prove troublesome within the historical literature.

Religion undoubtedly occupies an awkward place in the history of sexuality. Previously, historians of modern Britain either tended to ignore religious discussions of sexual issues (usually in favour of examining secular influences such as the law, medicine, or science), or to accept uncritically the perspectives of an earlier generation of historians that Christian views are essentially anti-modern, backward-looking, and against all challenges and changes to traditional Christian morality. However, newer scholarship, including my work on Church of England attitudes towards issues of sexuality in the years between 1918 and 1980, contribute to this emerging historiographical debate. Recent work is beginning to reassess our accepted views, and to develop a more critical approach towards the historical relationship between British Christianity and the rise of new ideas about sexuality, suggesting that the religious and the secular were not two separate, antithetical modes of understanding – rather there were considerable slippages, overlaps and exchanges between these approaches towards issues of sex and morality throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

Much of this literature makes a vital contribution to the field. By focusing on instances of Christian sexual progressivism, it refutes suggestions that religion was (or is) essentially the “other” of modern ideas about sexuality. Nevertheless, it is important to reflect more fully on the complications of religious, and especially institutional, decision-making on controversial questions of sexual morality. Wherever possible, we must confront head-on the question of who or what was actually representing “Christian opinion” or “the churches,” otherwise we are in danger of exaggerating the extent of religious consensus within certain denominations and thereby suggesting a relatively smooth and untroubled process of reconciling Church teaching with new sexual discourse. Even a cursory assessment of recent religious controversy over sexual issues exposes this as a misrepresentation of the relationship between Christian institutions and issues of sexuality, whether in the past or the present.

Throughout the twentieth century, the Church of England’s approach towards institutional decision-making on questions of sexuality was to try to pull contradictory views – held both within and without the British churches – into some kind of consensus. The Church sought to contain conflicting sections of opinion, search for compromise and reconciliation, and act as a moral mediator. In this sense, disagreements over issues such as homosexual law reform were highly significant and had a very real impact on developing debates. Disputes and tensions were built in to the very nature of Anglican sexual politics and determined the limits and extent to which many were prepared to support changes in approaches towards issues of sexual morality. The result was a series of pragmatic and often ambiguous Church positions on sex questions that stored up further conflict and later problems for the Church, especially in the years after 1970.

Even after declaring its official and public support for the Wolfenden recommendations, the CEMWC adopted a cautious approach towards the question of homosexual law reform. In the years after 1957, Anglicans remained fiercely divided and this had a significant effect on policy-making within the CEMWC. The Council supported the Wolfenden Report in principle and considered law reform an inevitable and desirable future prospect, but it also wrote to the Home Secretary in February 1958 urging the government “to resist pressure put upon it to frame hasty legislation, the effect of which might be to drive the problem underground, ignoring social realities as well as principles which society may well be found determined to uphold.” Instead of pursuing a campaign for sexual change, the Church did not (and could not) convert to a “permissive” position during this period. Rather, the CEMWC viewed the role of the government and Christian organisations in terms of encouraging “the education of public opinion” and fostering “informed discussion” in order that the social and moral issues “may be clarified and responsibility be accepted more widely by society.”

In the context of wider public discussion on these issues, disagreements among Anglicans were not a marginal concern. The compromises, tensions, and contradictions of Anglican debate represented a wider sense of opposition and unease around issues of homosexuality. This helps us to understand more about the relationship between British religion and sexuality in this period. Despite common assumptions that the Established Church was losing, or had lost, its influence in questions of sexual morality by the mid-1960s, key figures and organisations in the campaign for homosexual law reform continued to regard the Church of England as a crucial authority. Religious support for (and anxiety about) the emerging moral consensus in favour of decriminalisation really mattered and made a difference to British policy-makers, professionals, and other “experts” on homosexuality.

Later episcopal support for the 1967 Sexual Offences Act continued this trend of caution, offering only the illusion of Anglican consensus. Although the bishops, led by the Archbishop of Canterbury, Michael Ramsey, presented a picture of unanimity in the House of Lords, this concealed a considerable amount of disagreement. Some bishops who spoke in favour of the bill expressed private reluctance to do so; others refused outright to take part in the parliamentary debates. Lambeth Palace received so many hostile letters on account of the bishops’ stance, that it composed a standard letter of response. Consequently, episcopal support for homosexual law reform was full of contradictions and remained a fairly limited exercise in terms of radically changing Anglican attitudes towards homosexuality. The bishops’ case for reform may have used the rhetoric of freedom and choice for the individual within the context of personal moral responsibility, but it was also based on a fundamental belief that without criminal sanctions, the churches and other professional organisations (especially psychiatrists) would be in a better position to tighten up moral control and regulation. It was hoped in this way that homosexuality as a “problem” would eventually disappear. To this extent, the bishops’ position was more of an extension of Church leaders’ earlier attempts to find compromise and to search for a “moderate” and “responsible” solution to a difficult question of social and legal reform.

While it is important to recognise the contributions that religious individuals and organisations made towards shaping and popularising newer models of understanding sex and desire, conceptions of sexual morality, and ways of approaching “responsible” sexual citizenship in modern Britain, it is vital to locate this Christian sexual progressivism within its wider context – recognising the extent and nature of the conflict on controversial questions of sexual morality, both within and without British Christianity. The question of the part played by the Christian churches in broader social and cultural change has long fascinated historians. This is clearly an important issue that invites further comment and debate. While some suggest that the churches trailed society’s changing sexual norms, others argue that religious voices helped to lead and drive social and cultural change. But religious engagement with sexual matters in the twentieth century does not fit neatly or simply into this either-or dichotomy. Religious approaches, especially institutional ones, were considerably more complicated than that. Historians need to explore the contradictory pulls of Christian attitudes towards sexual issues, and to dissect their tensions and ambiguities. Not only will this illuminate the role of religion and Christian institutions in modern Britain, but it will help to bring out the complexities of our narratives on the making of modern sexuality – the continuities and discontinuities between older and newer ways of regulating and conceptualising sexuality, the uneven acceleration of shifts and changes, and the disputes, compromises, and calculations involved.

Laura Ramsay recently completed her PhD at the University of Nottingham. Her thesis explores Church of England attitudes towards issues of sexuality in the years between 1918 and 1980. This work addresses the difficulties and complications of institutional decision-making on controversial issues of sexual morality. While it identifies a long trend in Anglican thinking towards positive, constructive, and rationally-based statements about sex (which, it suggests, contributed towards a wider body of thought on issues that would later underpin “permissiveness” in the British context), it locates this Anglican thinking as part of a non-linear historical trajectory of Christian sexual progressivism. This work teases out the disagreements, ambiguities, and complexities of Anglican thought and examines the halting and uncertain advance of new Christian sex discourses among broader institutions like the Church of England. Laura tweets from @DrLauraRamsay.

Laura Ramsay recently completed her PhD at the University of Nottingham. Her thesis explores Church of England attitudes towards issues of sexuality in the years between 1918 and 1980. This work addresses the difficulties and complications of institutional decision-making on controversial issues of sexual morality. While it identifies a long trend in Anglican thinking towards positive, constructive, and rationally-based statements about sex (which, it suggests, contributed towards a wider body of thought on issues that would later underpin “permissiveness” in the British context), it locates this Anglican thinking as part of a non-linear historical trajectory of Christian sexual progressivism. This work teases out the disagreements, ambiguities, and complexities of Anglican thought and examines the halting and uncertain advance of new Christian sex discourses among broader institutions like the Church of England. Laura tweets from @DrLauraRamsay.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com

That’s a great analysis, Laura, and I’ll update my own very recent blog post on https://sharedconversations.wordpress.com/2016/03/28/meanwhile-back-in-the-toilet/ to incorporate a link. In more recent years it’s fascinating how voices in the C of E opposed civil marriage but then, when equal marriage was proposed, re-presented themselves as having supported civil partnership to make their opposition to equal marriage seem less…!

Hi Helen. Very pleased to hear you enjoyed reading the piece and many thanks for incorporating the link within your own blogpost. It also seems to me to be very interesting to see how in more recent years the C of E has drawn upon its history in dealing with issues such as homosexual law reform when presenting its contemporary views on issues such as civil partnerships.

Some confusions here about relationships between different parts of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. They are confusing relationships and so you are far from being the first to be confused. Your preamble paragraph on the Notches website refers to ‘Britain’, when there is no such country. The legislation, as you correctly, say refers to England and Wales, although the Wolfenden Committee had engaged with the whole of the UK. If you refer to Jeff Meek’s work, Queer Voices in Post-war Scotland, you can see some of the religious reasons which led to Scotland being excluded from the Sexual Offences Act of 1967. Scottish Presbyterianism is – and was – a very different beast from Anglicanism in England. To confuse matters further, while the (Anglican) Church of England is the established church in England, the (Presbyterian) Church of Scotland is the established church in Scotland. Although the Queen is head of both churches, there really is no institutional phenomenon that can be said to encompass what you call British Christianity. As I said above, it is a complex and confusing set of relationships and I only point it out to clarify things and to be supportive of you and your research.

Bob Cant

Hi Bob. Thanks for your comments – you raise some important issues here. There are a few elements that I would like to reply to, however, lest my work be misunderstood or misrepresented. My preamble refers to the ‘British government’ which is a commonly used, and widely recognised, term that seems to me to be suitable in this context. I make no claims to have established all the answers to the complicated relationship between Christianity in the UK and issues of sexuality, I am simply adding to a much wider historiographical debate on this (and Jeff Meek’s work, as you rightly point out, is an important part of this ongoing discussion and has featured recently on Notches). My work to date focuses on the Church of England and so, as you say, only extends to Anglicanism in England. The post makes no claim that the Church of England is tantamount to ‘British Christianity’. The point that the blogpost is making is that institutional decision-making was a very complicated process – I fully appreciate that and hope the blogpost allows others to understand that too. In fact, an important point that the post raises throughout (and that I think your comments are getting at) is that we have to be attentive towards the difficulties of determining who or what was representing the Church of England, let alone wider Christian groups and organisations in the UK. The point I am making about the various Anglicans who supported homosexual law reform is that they could not claim to represent their wider institution as a whole. I am also careful to point out that the law reform discussed in this piece only applied to England and Wales. I think what you have picked up on here is more of a wider issue on how we actually bring these discussions together into a more comprehensive study of the relationships between religion and sexuality in the whole of the UK. This is certainly a very worthwhile project but there has been little done so far to try to knit together these very interesting discussions about different elements of Christianity in the UK. Thanks again for your interest in my work.

Hi Laura – thanks for your message.

When I first read your blog this morning on Facebook, the preamble (which I now understand you did not write) said: “The Sexual Offences Act decriminalised homosexual acts committed between consenting adult men in private in Britain.” When I pointed out on Facebook that there is no such country as ‘Britain’, I was advised to contact you directly. By the time I had done so, the preamble paragraph had been altered to read, as it does now, “adult men in private in England and Wales”. I am sure that we are both pleased that it is now historically more accurate than it was.

The situation with regards to established churches and their views on homosexuality is complex. As I said above, I am not altogether happy with terms such as ‘British Christianity’ for reasons that I am sure that you will understand. I found the core of your argument about the complexities of the debate within the Church of England very illuminating and I look forward to reading about the next stages of your work in this field.

Bob

Hi Bob. Many thanks for explaining how this confusion arose. I hadn’t seen the earlier post on Facebook but thank you for pointing out the mix-up there. I’m pleased to hear you enjoyed reading the post and thanks again for offering your thoughts on the difficulties of handling the complicated relationships between religion and sexuality.

Hello,

Thank you for this article. IS there any chance you can point me in the direction to find a copy or at least more pictures of that report from the Church of England Moral Welfare Council (CEMWC) ? I need primary sources for an essay.

Thank you