Moderated by Regina Kunzel

We invited Regina Kunzel to moderate a three-part roundtable on histories of sexuality and the carceral state (check out part one). Critical prison studies has understandably foregrounded questions of race in an effort to expose and understand the dramatic overrepresentation of incarcerated people of color, revealing how the growth of punitive practices and policies have maintained and hardened racial hierarchies. We know far less, however, about how the policing of sexuality has contributed to the growth of state mechanisms of surveillance and incarceration, and how sexual policing might have worked, alongside and often in collaboration with punitive racialization, to drive the larger carceral turn. In this second post, Sarah Haley, Elias Vitulli, Jen Manion, and Scott De Orio discuss the multiple ways that race, gender, and sexuality intersect in order to shape policing and imprisonment.

Regina Kunzel: It’s clear from your great responses that among the things that we bring to the history of the carceral state, as historians of sexuality and gender, is an intersectional analysis that recognizes the connections among different forms of marginalization and exclusion. Can you offer some examples of how, in your respective projects, you see sexual policing and containment working alongside and in collaboration with racialized practices to drive incarceration and structure the carceral state?

Sarah Haley: I’m grateful for this question because intersectionality dramatically reshapes our understanding of difference and the structure and operation of the law. One of the things I find most powerful about the intersectionality frame is its applicability for historical understandings of power.

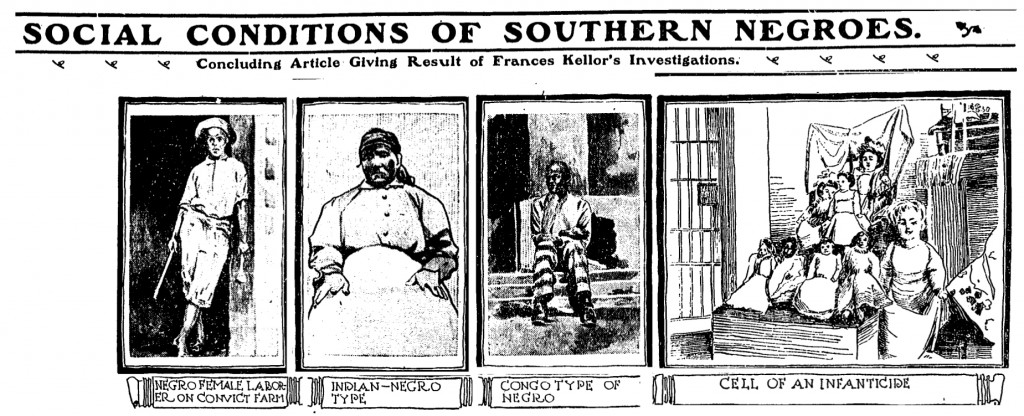

Policing and incarceration both construct and fortify intersectional sexual, gendered, racial, and class structures and relations of power. For example, black women in Jim Crow Georgia were arrested more often for infanticide than prostitution. Although ideas about their deviant sexuality contributed to the view that black women were unfit mothers, it is significant and perhaps unexpected that black women were charged with violating the codes of motherhood more than they were for deviating from sexual rules of behavior. One reason for this is that black mothers were blamed for the disorder of black neighborhoods and their children’s defiance at work. Journalists circulated depictions of the iniquity of the black female-led household and black women were routinely charged with infanticide solely on the basis of complaints and testimonies about the alleged disappearance of babies, or accusations that a woman had been pregnant but never had the child. As critical race theory has taught us, the law draws “taxonomies that purport to make life simpler in the face of life’s complication.” This feature of legal doctrine produces, maintains, and fortifies existing power relations. It is no surprise then, that when the death of a black infant could be confirmed, the evidence suggesting that he or she died as a result of malnutrition, inferior living conditions, and work-related accidents was ignored. Newspaper accounts reported cases in which white women were believed to have killed their children, but these stories did not include lurid language and detail, and they were almost never prosecuted. In a rare case in which a white mother was accused of infanticide, her prosecution drew statewide attention and outrage.

In addition to maternal policing, black women were routinely raped in southern convict leasing camps and on chain gangs. This form of carceral sexual control was not meant to make them into good, docile sexual citizens but, as I mentioned in my earlier post, to reinforce racial and gendered social orders that undergirded capitalist production. The rape of black women in convict camps reasserted their dual status as laborers without rights and degraded objects; their guards consumed their bodies as a work benefit.

Intersectionality helps us understand how black women were outside of legal boundaries of recognition as demonstrated by their frequent convictions in court on spurious charges of unfit motherhood. As a metaphor, it also helps us understand the complexity of historical contingency. The courtroom and the convict camp are clearly institutional grounds where race, gender, and sexual domination converge, or intersect. However, the metaphor demands that we remind ourselves that these institutional forms are constituted by active work of historical figures, and by ideologies that are shifting, contested, and relational.

As Kimberlé Crenshaw writes, “Discrimination, like traffic through an intersection, may flow in one direction and it may flow in another. If an accident happens in an intersection, it can be caused by cars traveling from any number of directions and, sometimes, from all of them.”

One of the reasons that intersectionality is particularly useful for historians is that it encourages a research agenda that considers both the process through which specific vectors of power are produced, and the point at which they come together to produce unique and disparate institutional harm. In other words, historians are uniquely positioned to research and explain the traffic that then collides at the intersection.

For example, ideas about black women’s maternal deviance took hold through rumor, innuendo, testimony, conflict, movement and migration, material displacement, labor regulation, discretionary practices of surveillance and policing, and popular narratives. These made it possible for black women to suffer prolonged periods of captivity for charges of infanticide. As a framework that emphasizes movement as much as immobilization, intersectionality allows for historical examinations of how ideas about race and gender (for example) developed alongside each other (on the same road), and continued to develop through collision (as categories whose meaning is produced through conflict, contestation, and dissonance in particular historical moments). In this way, intersectionality powerfully lends itself to historical research that seeks to explain how gendered and sexual carceral political geographies evolve and are fortified, are made and unmade.

Elias Vitulli: My research focuses on how prisons and jails in the U.S. have managed gender nonconformity since the early twentieth century. As a starting place, it is important to understand that the vast majority of trans and gender nonconforming people in jails and prisons are low-income people of color. All trans and gender nonconforming people are vulnerable to state surveillance and violence. However criminalization, and experiences of policing and incarceration, fracture trans experience and life chances. This fracturing is fundamentally the result of racial, sexual, and class regimes of power construction, and fortification of the discursive and material ways that gender nonconformity is criminalized, to extend Sarah’s excellent framing.

An intersectional framework is also vitally important to understanding management practices within penal institutions, which is the focus of my research. For example, this framework can help us rethink how segregation functions as a management technology of the carceral state. Segregation is usually framed as a means to neutrally sort and punish prisoners in order to secure the safety of penal institutions, their staff, and their general prisoner population. However, segregation actually produces certain bodies and populations that are constructed to be fundamentally dangerous and undeserving of care, safety, or rights, thereby fortifying intersecting regimes of domination. This management practice is central to the order and operation of the carceral state.

Segregation is one of the modern prison system’s oldest management practices. First used within the penitentiary system as the central tool for rehabilitating white male prisoners, within a few decades segregation was primarily used to punish and contain problem prisoners, as individuals and as populations. Many jails and prisons were racially segregated through the mid-twentieth century — and some continue to be. As Liat Ben-Moshe and others have shown, segregation has also been a primary tool of state management of disabled people — as disabled people have been segregated from “normal” society by way of asylums, institutions, group homes, and jails and prisons. Within jails and prisons, disabled people, particularly cognitively and mentally disabled people, have been segregated. Segregation often produces disability, as many people literally “go mad” from the extreme violence and isolation of segregation itself.

Incarcerated gender nonconforming people have also been systematically segregated from the general population since at least the early twentieth century. By the 1930s, the segregation of gender nonconforming prisoners was common practice in men’s jails and prisons throughout most of the U.S., particularly outside of the South. Penal administrators justified this segregation by portraying gender nonconformity as dangerous to institutional security. How they articulated that dangerousness, of course, shifted over time. For example, in the early twentieth century, gender nonconforming prisoners were constructed as direct threats, causing (sexual) disorder and violence. This articulation began to shift in the 1960s and 1970s as prison administrators increasingly argued that segregation protected gender nonconforming prisoners — a shift that relied on new articulations of prisons as sites of rampant racialized sexual violence, perpetrated by black men, which Regina Kunzel described in her book Criminal Intimacy. Despite changes in discourse, the material use of segregation has remained a constant, if unevenly applied, management practice for over one hundred years that effectively produces gender nonconformity as a danger, a sexual threat to institutional life that justifies the violent isolation of gender nonconforming and trans prisoners.

Most recent work in critical prison studies on segregation within prisons and jails has focused on the emergence of security housing units (SHU), supermax prisons, and control units since the 1970s. Scholars such as Dylan Rodríguez, Colin Dayan, and Alan Eladio Gómez have argued that this penal technology was developed as a response to multi-racial but especially black nationalist prison organizing in the 1960s and 1970s. This genealogy frames segregation as a racialized, particularly anti-black, technology of domination, dehumanization, and behavior modification. Looking across forms, sites, and even time periods of segregation through an intersectional framework, we can understand segregation as a management practice wielded against deviant and unruly bodies, simultaneously an anti-black, white supremacist, hetero-gender normative, and ableist technology that discursively and materially constructs certain prisoners as particularly dangerous, justifying their social and bodily confinement and dehumanization. Within this frame, we should not only focus on how disabled queer and trans people of color are most likely to be placed in segregation, but how the logics of segregation enable racial, gender, sexual, and dis/abled dehumanization and violence, which is deeply imbedded in what the carceral state does within and outside institutional walls.

Jen Manion: Following the American Revolution, there was a strong desire among elites to revise the penal code and differentiate it from that of Great Britain. The policing of sex was one area they felt particularly strongly about — contending that it was too harsh, irrational, and void of sympathy. They decided laws concerning rape, sodomy, and infanticide were barbaric and representative of everything that was wrong with old England. The result was a transformation in attitudes towards women accused of infanticide — from a presumption of their guilt to a presumption of their innocence. Sodomy was removed from the list of capital crimes. The courts also became less invested in punishing people for fornication and more readily granted women divorces. All of this can be described as a loosening and liberalizing of sexual norms in the young nation.

The liberalizing of sexual norms was uneven, however. The liberalizing of sexual norms for certain groups served to mask and deflect the role of sexuality in structuring the carceral state. This is particularly visible when one considers the increased criminalization of women who may have engaged in sex work. This is why an intersectional approach — as Sarah has so powerfully illustrated — is crucial to understanding the reach and aim of carceral culture. Women who walked the streets at night and offered sexual intimacies in exchange for money in the colonial period were harshly judged though largely ignored by authorities. This changed in the early national period as elites sought to regain control of public spaces in the heart of downtown Philadelphia, just as formerly enslaved African Americans flocked to the city. City officials felt burdened by the cost of their poor relief efforts and modified the vagrancy law in 1789 to criminalize vagrancy, ordering the imprisonment of vagrants for thirty days without trial alongside of convicts in jail.

Pennsylvania became a destination for free blacks and runaway slaves alike after 1780 when it passed the Gradual Act. African American women who walked the streets at night for countless reasons — from enjoying each other’s company to looking for work — were increasingly likely to be charged with vagrancy. Pennsylvania elites who recognized slavery’s wrongs were not exactly ready to embrace the realities of black freedom. Night watchmen were ordered to rid the streets of anyone deemed a nuisance, and they exercised incredible discretion in doing so. The effect of being imprisoned under the new vagrancy policy was devastating. Not only would someone be torn from their family without explanation and lose whatever employment they may have had, but they would be criminalized. The criminalization of free blacks through vagrancy charges in the early republic served to undermine the possibilities for true freedom.

For some women, sex work was their best way to earn much needed income or supplement poorly paid work as washerwomen or servants. By all accounts, there was a vibrant sexual culture in the early nineteenth century in Philadelphia and disorderly and bawdy houses operated relatively undisturbed. Engaging in sex work itself did not seem to be the target but rather an excuse for arresting women who were walking in groups, especially if they dared to make noise or enjoy themselves. There was a longstanding belief perpetrated by male prison guards and constables that all of the women in the vagrancy section of the prison were prostitutes, even though most of them were imprisoned under different charges — such as being homeless or unemployed.

I think the key to understanding how ideologies of race and sex were deployed in tandem to drive the carceral state is often found between the lines, especially in the Early Republic when there were actually very few explicit discussions of race and racial difference in punishment. These two massive structures were being transformed separately but in tandem — the abolition of slavery and the creation of the penitentiary. One of the most powerful lessons from working on Liberty’s Prisoners for me was the ability of progressive whites to convince themselves that something was not about race when in fact it was all about race. City officials convinced the public that policing the streets of these women was about sexual morality, when in fact it was also or even chiefly about racial order, class discipline, and gender norms.

Scott de Orio: Two centuries after the police used vagrancy laws to criminalize black women in early Philadelphia, the police used vagrancy laws to punish the non-normative sexual conduct of gay men.

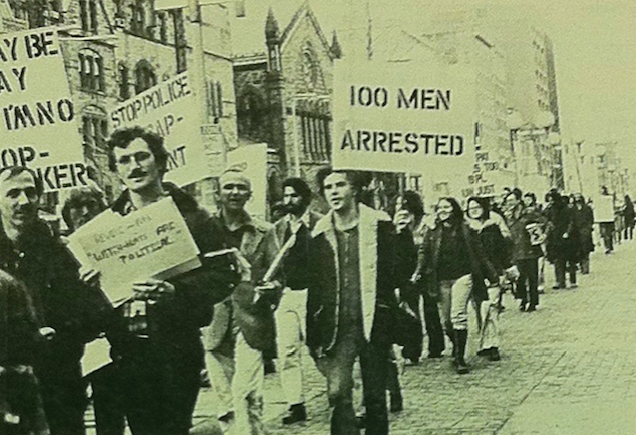

In the third week of March 1978, gay activists noticed an extraordinary increase in police activity in the men’s room on the first floor of the Boston Public Library in Copley Square. Police records indicated that nearly fifty men had been arrested there over a five-day period on various charges ranging from “open and gross lewdness” — a modern iteration of the older legal notion of vagrancy — to prostitution. Most of the arrests were made by Officer Angelo Toricci, an “attractive, young” plainclothes officer who, according to some of the men he arrested, stood close to the urinals “masturbating himself to encourage sexual advances.” The crackdown at the library came on the heels of another police witch-hunt of adult gay men accused of having sex with teenage boys. The Suffolk County District Attorney Garrett Byrne had indicted 24 men for over 100 felonies for having consensual sex with teenage boys in what he erroneously referred to as a “boy-sex ring.” The police were conducting a veritable war on “bad” gay men whose sexual behavior violated widely accepted canons of propriety and decency.

The Boston gay community’s response to the police repression benefitted from the support of the prominent black politician Mel King. On Saturday, April 1, more than 200 people demonstrated in front of the Boston Public Library and at the police headquarters to protest the police department’s harassment and entrapment at the library. The marchers carried signs reading, “I May Be Gay But I’m No Cop-Sucker,” “Gays Pay Taxes Too,” and “Cops on the Beat Not Beating Off.” Activist David Drolet read a statement from Mel King, a black State Representative for the 9th Suffolk District, who apologized for not being able to attend the protest and expressed his support for its goals. Though he could not attend the rally, King did the gay movement one better by filing legislation directing the state Attorney General to investigate “allegedly unlawful conduct” by police officers in Boston District Four.

An intersectional frame of analysis throws into relief how, as Jen put it so well, “ideologies of race and sex were deployed in tandem to drive the carceral state.” By virtue of their common experience of being marginalized by the police, black and gay activists in Boston and other U.S. cities formed ad hoc coalitions in the 1970s to oppose unjust police practices. Mel King’s support for the Boston protest is the same kind of black-gay coalition against unjust police practices that Timothy Stewart-Winter examines in his new book about Chicago. Intersectionality, then, is a key mode of analysis that I use at certain points throughout my work like this one to reveal moments of organized resistance to the expansion of the carceral state. These moments of resistance serve as an important reminder that the expansion of the carceral state was not inevitable but rather was the product of contingent political contests in the past.

While intersectionality is one of the modes of analysis that I use in my project, though, I would not say it is at the heart of my work. Rather, my project is invested in placing sexuality at the center of its analysis to examine the history of the war on sex offenders and its concomitant construction of a legally enforced hierarchy of sexual value and citizenship. In the future, it will be necessary for somebody to write a history that treats the war on sex alongside campaigns against racial minorities in order to provide a synthetic account of the multiple drivers of the rise of the carceral state. For now, however, I argue that the history of the carceral state needs a monograph that investigates the war on sex since the 1970s as a relatively distinct historical phenomenon and treats sexuality as a relatively autonomous category of analysis.

Regina Kunzel is the Doris Stevens Chair and Professor of History and Gender & Sexuality Studies at Princeton University. Her most recent book is Criminal Intimacy: Prison and the Uneven History of Modern American Sexuality (University of Chicago Press, 2008). She is currently working on a book exploring the encounter of sexual- and gender-variant people with psychiatry in the mid-twentieth-century U.S.

Regina Kunzel is the Doris Stevens Chair and Professor of History and Gender & Sexuality Studies at Princeton University. Her most recent book is Criminal Intimacy: Prison and the Uneven History of Modern American Sexuality (University of Chicago Press, 2008). She is currently working on a book exploring the encounter of sexual- and gender-variant people with psychiatry in the mid-twentieth-century U.S.

Sarah Haley is Assistant Professor of Gender Studies and African American Studies at the University of California, Los Angeles. Her research focuses on black feminist analyses of the U.S. carceral state from the late-nineteenth century to the present, black women and labor, and black radical traditions and organizing. She received her PhD in African American Studies and American Studies. Her first book, No Mercy Here: Gender, Punishment, and the Making of Jim Crow Modernity (UNC Press, 2016), examines the lives of imprisoned women in the U.S. South from the 1870s to the 1930s and the role of carcerality in shaping cultural logics of race and gender under Jim Crow. She has also worked as a paralegal for the New York Office of the Federal Public Defender and as a labor organizer with UNITE-HERE. She tweets from @sahaley.

Sarah Haley is Assistant Professor of Gender Studies and African American Studies at the University of California, Los Angeles. Her research focuses on black feminist analyses of the U.S. carceral state from the late-nineteenth century to the present, black women and labor, and black radical traditions and organizing. She received her PhD in African American Studies and American Studies. Her first book, No Mercy Here: Gender, Punishment, and the Making of Jim Crow Modernity (UNC Press, 2016), examines the lives of imprisoned women in the U.S. South from the 1870s to the 1930s and the role of carcerality in shaping cultural logics of race and gender under Jim Crow. She has also worked as a paralegal for the New York Office of the Federal Public Defender and as a labor organizer with UNITE-HERE. She tweets from @sahaley.

Elias Vitulli is a Visiting Lecturer of Gender Studies at Mount Holyoke College. His research explores the connections between queer/transgender studies and critical prison studies. His current project, “Carceral Normativites: Sex, Security, and the Penal Management of Gender Nonconformity,” explores the history of the incarceration of gender nonconforming and transgender people in the U.S. from the early twentieth century to the present, focusing on the evolution and logics of penal policies and practices. He received his PhD in American Studies, with a minor in Feminist and Critical Sexuality Studies, from the University of Minnesota in 2014. His work has appeared in GLQ, Social Justice, and Sexuality Research and Social Policy.

Elias Vitulli is a Visiting Lecturer of Gender Studies at Mount Holyoke College. His research explores the connections between queer/transgender studies and critical prison studies. His current project, “Carceral Normativites: Sex, Security, and the Penal Management of Gender Nonconformity,” explores the history of the incarceration of gender nonconforming and transgender people in the U.S. from the early twentieth century to the present, focusing on the evolution and logics of penal policies and practices. He received his PhD in American Studies, with a minor in Feminist and Critical Sexuality Studies, from the University of Minnesota in 2014. His work has appeared in GLQ, Social Justice, and Sexuality Research and Social Policy.

Jen Manion is Associate Professor of History at Amherst College. Manion is author of Liberty’s Prisoners: Carceral Culture in Early America (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015) and co-editor of Taking Back the Academy: History of Activism, History as Activism (Routledge, 2004). Jen has also published essays in Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, Journal of the Early Republic, TSQ: Transgender Studies Quarterly, and Radical History Review. Manion was awarded a National Endowment for the Humanities Fellowship at the American Antiquarian Society in 2012-2013 to research a new project, “Born in the Wrong Time: Transgender Archives & The History of Possibility, 1770-1870.” Manion tweets @activisthistory and posts articles about contemporary mass incarceration at Liberty’s Prisoners on tumblr.

Scott De Orio is a doctoral candidate in History and Women’s Studies at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. His research focuses on the history of sexuality in the twentieth-century United States with a particular interest in law and state power. His dissertation, entitled “The Invention of Bad Gay Sex,” examines how new sex offender laws constructed a criminal underclass of gay people in the late-twentieth-century United States.

Scott De Orio is a doctoral candidate in History and Women’s Studies at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. His research focuses on the history of sexuality in the twentieth-century United States with a particular interest in law and state power. His dissertation, entitled “The Invention of Bad Gay Sex,” examines how new sex offender laws constructed a criminal underclass of gay people in the late-twentieth-century United States.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com