Debbie Does Dallas, the famed 1978 pornographic film, briefly made my great uncle, Robert Porter, a Republican-appointed federal judge in Texas, a minor celebrity. His obituary features “banning” Debbie as his career’s pinnacle, highlighting the paradoxical relationship between a certain variety of Republican and pornography. Despite conservative protestations about immorality and oft-repeated pledges to eradicate it, history shows these unlikely bedmates commingle frequently and fervently enough to suggest a mutually beneficial arrangement. Consider their anti-porn crusades; the outcomes of such efforts typically matter far less than the spectacle of the attack itself. In the 1970s, Deep Throat (1972), Debbie Does Dallas (1978), and other films of that ilk revolutionized America’s relationship with pornography through their playful publicity, masterful marketing, and catchy comedy. Furthermore, they became sources of celebrity – or at least notoriety – for anyone associated with them and seduced many conservatives to rail against them as means of galvanizing constituents.

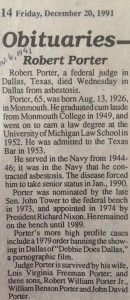

In my uncle’s case, even the traditionally solemn, staid death notice was marked by this association: twelve years after his Debbie debacle, Porter’s obituary cites a connection with hardcore porn as casually as it catalogs surviving relatives, illustrating a sea change in the relationship between conservatives and porn. As an artifact, this obituary presents a mystery: its author and his/her motives for denouncing Debbie in a death notice are open to debate.

Evaluating the writing style and content – and considering his single-handed orchestration of his funeral and burial, and the input of my relatives – I am convinced my uncle authored and released this final piece of PR as a parting fortification to his sterling conservative reputation. Known locally as “The Judge,” Porter enjoyed a favorable reputation that he wished to safeguard posthumously, tweaking the narrative to amplify his role in the anti-porn crusade.

But he did not, in fact, ban Debbie; he issued a temporary injunction against its screening and later helped usher it into theaters by directing its creators to remove advertisements implying a direct connection to the Dallas Cowboy Cheerleaders. When, by way of his obituary, I discovered that my John Tower-nominated, Richard Nixon-appointed, model conservative of a federal judge uncle, through his rulings, had heightened the public’s outrage about Debbie while also arousing their interest in it, I immediately assumed that as a staunch conservative he was playing activist judge and banning Debbie, in Dallas no less, as obscene. His public persona influenced my analysis, as it was fashioned to do.

If his actions evoke strains of Jesse Helms, Saxby Chambliss, or even George Herbert, we must consider that he operated in a legal system having its first encounters with the complications attendant upon the mainstreaming of porn, which differed greatly from its earlier, more hidden incarnations.

From our vantage in a porn-saturated world, my great uncle’s treatment of Debbie may appear clichéd – predictable, even – but I would argue that appraisal stems from his style of response having become de rigueur with conservatives since then. This modus operandi characterizes conservatives’ fraught porn relationship, which studies suggest they consume as avidly as they denounce it. Still, conservative politicians deftly understand that attacking pornography in public also gives them a measure of porn’s undeniable power, while also deflecting reproach for hitching their [band]wagons to that particular [porn]star.

My great uncle ensured his reputation when he theatrically ordered the film’s confiscation; he performed his duties pro forma while conveniently catering to public opinion. But while his initial injunction asserts that the law prohibited its screening – due to the advertisements in the film implying a direct connection with the Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders, Inc. – he later advised its creators about the necessary editing so that the film might be shown. This particular effort on his part suggests that his own interests were best served by getting publicity for its banning, while recognizing that he could only truly capitalize upon the situation if Debbie did not fade from the public eye too quickly. In a larger sense, it also suggests that for conservatives with their free market ideology, profit (in whatever form) always takes precedence, even when it comes to pornography.

In emphasizing Debbie‘s banning in his own obituary as his greatest legal achievement – despite adjudicating many other important, albeit less splashy, cases – he misrepresented his rulings as taking a stand against porn. He also fashioned himself as a conservative bravely decrying Debbie’s dangerous doings, obscuring his pivotal role in the film’s eventual release. In that crucial role, the judge from Dallas, in spite of his robust public performance as a conservative Republican, ultimately decreed every detail of what Debbie did in Dallas.

Joshua Adair is an Associate Professor of English at Murray State University, where he also serves as director of the Racer Writing Center and coordinator of Gender and Diversity Studies. He has published about the work of Beverley Nichols and Christopher Isherwood, as well as the presentation of queer lives in historic house museums.

Joshua Adair is an Associate Professor of English at Murray State University, where he also serves as director of the Racer Writing Center and coordinator of Gender and Diversity Studies. He has published about the work of Beverley Nichols and Christopher Isherwood, as well as the presentation of queer lives in historic house museums.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com