Civil War soldiers shared all sorts of things. They read out loud to one another, looked after each other when sick or injured, bunked up when necessary, and when it was safer or more comfortable than other options, and posed together in photographs. On occasion, they shared bawdy magazines, obscene playing cards, and the lyrics of naughty songs. The sharing of erotica formed part of the sexual culture of U.S. military camps that I explore in my book, Sex and the Civil War. Through these media, men sought to reaffirm period notions of fraternity and maybe even to reaffirm life in the midst of the death with which they were surrounded.

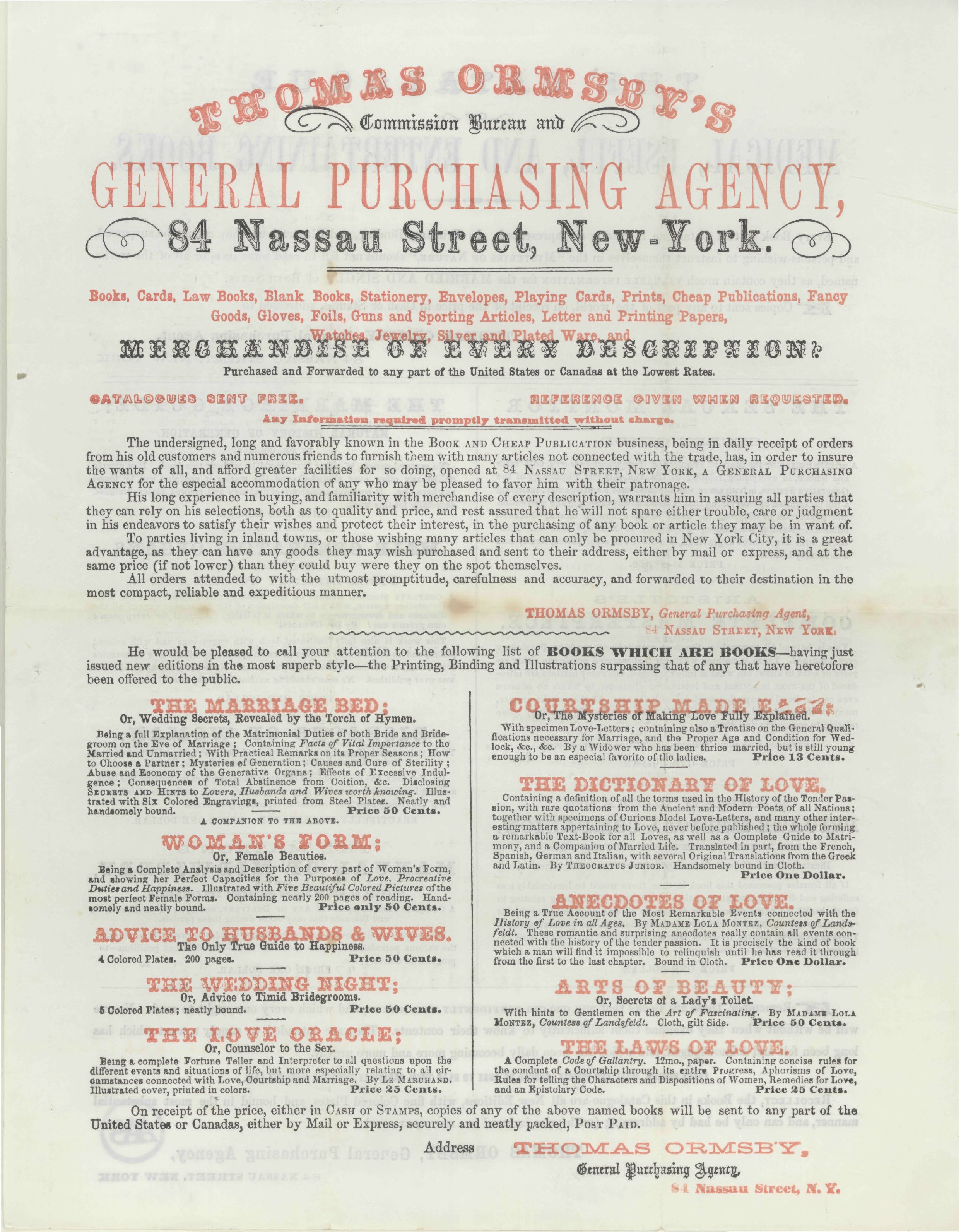

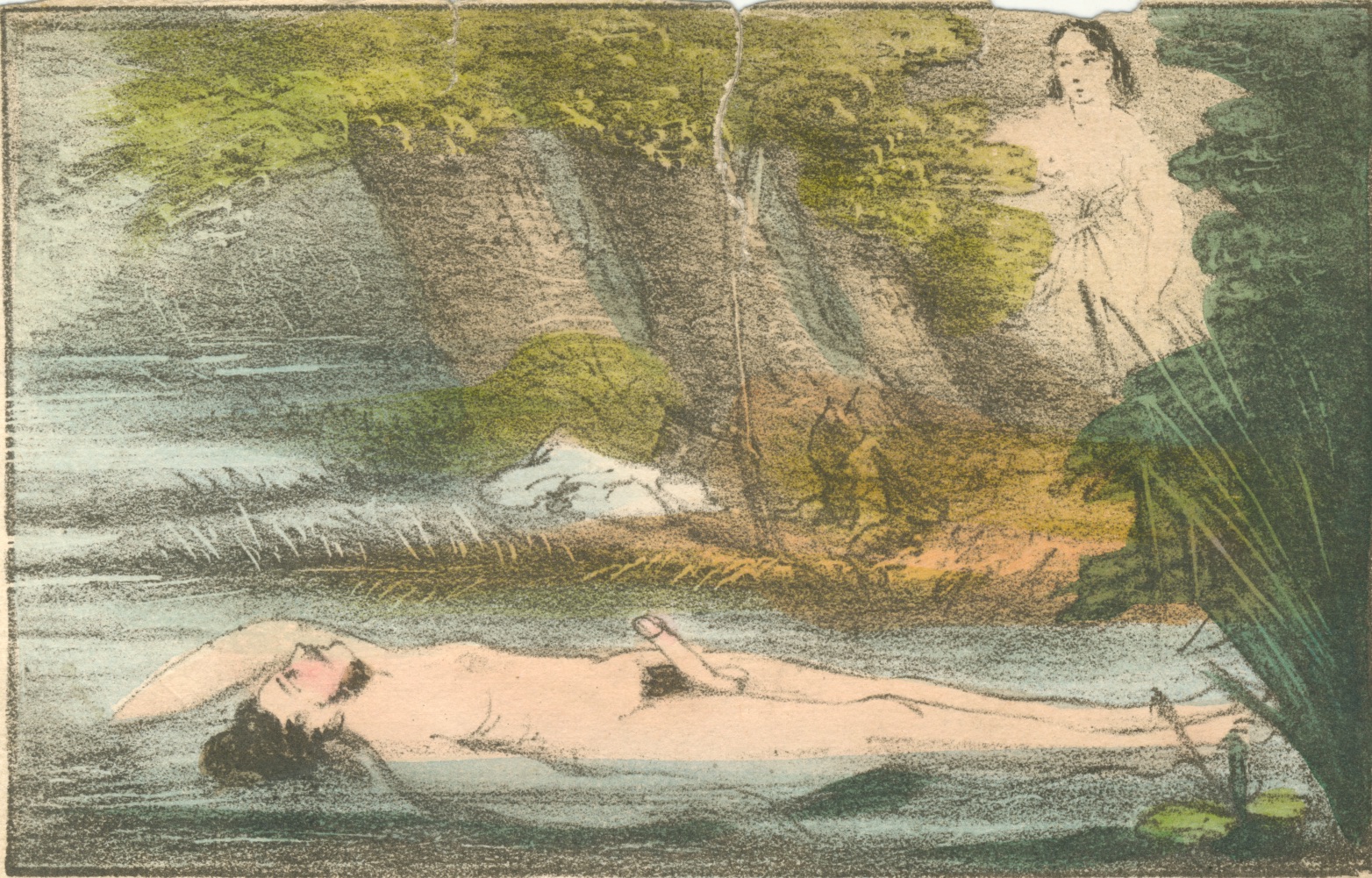

Sex and the Civil War examines the erotica available to the fighting men and how they interacted with it. This includes works like Fanny Hill, or Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure, mentioned in an 1862 U.S. Court Martial proceeding. Originally published in England in 1748, Fanny Hill tells the story of a naïve country girl lured into a life of prostitution. The book reads like a catalogue of naughty acts, including same-sex acts, sex in public, and, a period favorite, flagellation. Some men at the front complained about the number of obscene prints and circulars, the former available at low cost to the men and the latter distributed free of charge as an inducement to order items through the thriving mail-order business that came to life during the conflict. Writing from Blue Springs, Tennessee, in 1864, Captain M. G. Tousley complained to his superiors about the circulars that “were continuously distributed in large numbers” among the men, which he believed “add greatly to the unavoidable influences that thus demoralize.” An anonymous soldier expressed similar concerns in a letter to a newspaper, describing men “reading flimsy publications, obscene books, and the worst species of yellow-covered literature.”

There seemed to be no shortage of these materials, but historians have not spent a lot time thinking about Civil War erotica. When we think of the Civil War we like to think of its noble outcomes—union and emancipation—and the idealism of its soldiers. Perhaps this explains why Civil War scholars have steered clear from the topic. And, then there are the other problems—soldiers did not keep erotica, and archivists have not collected it. Most of the stuff lives in private collections, tucked away in folders and boxes, instead of being archived in public collections. Yet, men did not hide it in the camps. In one court martial, a group of Massachusetts soldiers reported seeing a copy of Fanny Hill in the hands of a number of different officers, on the ledge of tent, on a desk, and then in a drawer, presumably open, and under a mattress. Well, that last sighting might have been an attempt to hide the book, but in any case, the book seemed to have been popular.

As noble as were the causes for which they fought, men in Civil War armies derived their identities from one of several different cultures of nineteenth century manhood, for instance from the working-class “roughs” that historian Lorien Foote describes, or from the “gentlemen” who treated the roughs with disdain. Sex and desire were part of their identity, though historians have generally looked for evidence of soldiers’ sexual lives when women were in the picture—as visiting wives or prostitutes, for example. But women were also in pictures that men enjoyed alone and together. When men shared erotic images and words, they negotiated and cemented lines of authority, as these materials served as a form of bonding, drawing men together who otherwise had very little in common and reinforcing their trust. Through these media, men reaffirmed period notions of manliness and homosociality, sharing images and words in much the same way as they expressed emotional intimacy in their correspondence and in the un-self-conscious way they posed together in photographs.

I learned a couple of things that may be of interest to scholars. First, pornography only became a problem for commanding officers when men were not engaged actively in campaigns. The rigors of campaigning imposed a discipline on the men that left no time for concerns about what they were reading or tucking into their haversacks. And, like the stock character in period pornography—the voyeur—men expected to have visual access to one another, where they kept close watch on each other, regardless of rank. This latter observation is of consequence, it seems to me, because much of what we know about the way discipline was meted out in the US Army suggests that the advantages were stacked heavily in favor of the “gentlemen of rank” who made the rules and administered military justice. Yet, at the foundation of the sexual culture of the camps, lay a set of rules and expressions based instead on the rough manhood of the working classes, expectations laid out—and lavishly illustrated—in period erotica.

Those who began to define “the problem of pornography” were those who sensed that they had something to lose in this alternative set of rules—namely army whistleblower Anthony Comstock and a group of US congressmen who launched a campaign against pornography. Sold as measures to protect men from the evil purveyors of porn, postwar anti-pornography measures responded to the leavening effect of porn and the democratization with which it was associated. These concerns dovetailed with midcentury anxieties about miscegenation. Indeed, slave owners were often likened to vampires for their lack of restraint and the effect slavery was having on the nation’s “life-blood;” so too were pornographers. “[W]hen it became possible that anything at all might be shown to anybody,” Lynn Hunt has explained, “there emerged a strong desire for barriers, catalogues, new classifications, and hygienic censoring.” The Civil War was such a moment. When we find the erotica and study it, I like to think we are working against the project of anti-pornography—the effort to censor it, to hide it away—in order to reinstate it as a part of a sexual culture and a human experience about which we still know less than we should. The Civil War is not any less noble for the humanization of the men who fought it.

Judith Giesberg is a Professor and a Director of the Graduate Program in History at Villanova University and an Editor of Journal of the Civil War Era. She publishes on topics related to race and gender and the U.S. Civil War. Her recent publications include Army at Home: Women and the Civil War on the Northern Home Front, and Emilie Davis’s Civil War: The Diaries of a Free Black Woman in Philadelphia, 1863-1865.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com