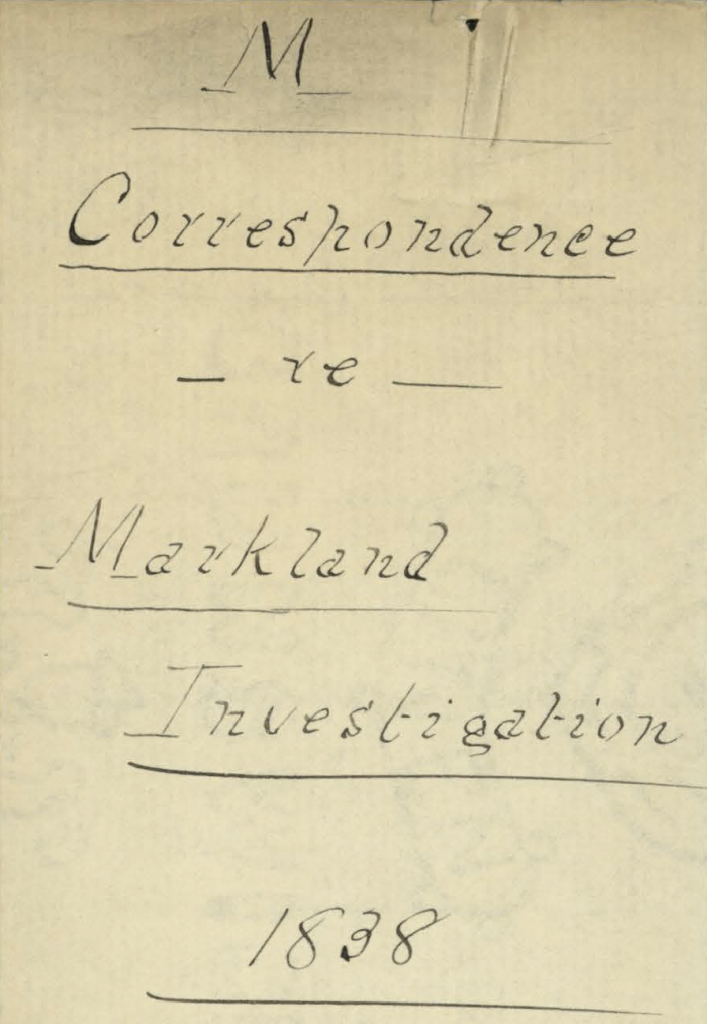

In August 1838, five young Upper Canadian men—two labourers, a piper in Her Majesty’s 24th Regiment of Foot, a law student, and a local merchant—were questioned about the ways that their male bodies came into contact with that of another man, the colony’s inspector general, the Hon. George Markland. Their testimonies—the “facts of the case” as University of Toronto Librarian W. S. Wallace once called them—recorded as part of a secret state inquiry into Markland’s “habits” and “character” have primarily been read by historians in an effort to determine if Markland was having sex with men. But the elite family compact men on the Executive Council who led the investigation were unable to answer such a question, and I make no such attempt now.

Instead I read the layered testimony of John Brown, James Pearson, Henry Hughes, Frederick Muttlebury, and Henry Stewart for what it can teach us about how their manhood and sexuality were troubled by intimate and physical contact with another man. Did they consider male same-sex contact appropriate on the city’s sidewalks? In public parks? How did they feel about holding another man’s hand? What were their affective responses to physical contact with another man? What limits did they place on different forms of male contact? Here I argue that the testimony of those touched by the Honourable George Markland sheds light on the boundaries—both physical and affective—of appropriate or proper male same-sex intimacy. In short, these men’s responses to Markland’s touch help historicize homophobia in early-Canada.

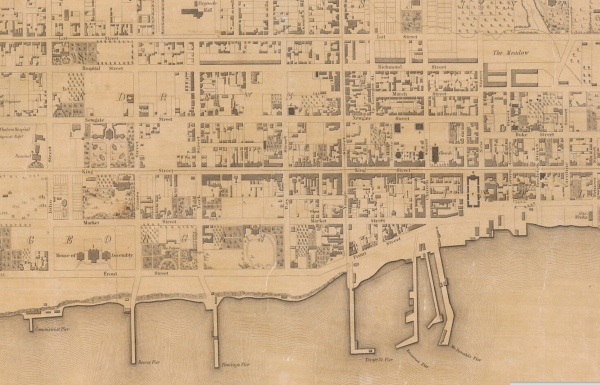

Evidence suggests that Markland frequently met men on the grounds of public buildings and on Toronto’s streets. It was also there that male bodies first made physical contact. The Toronto Labourer John Brown testified that on a February evening he had “met a man in the Yard” and only discovered later that it was Markland. Markland had invited James Pearson, a piper in Her Majesty’s 24th Regiment of Foot, to the public grounds when they met “on a walk on the wharf.” Henry Hughes met Markland on his way home from work. All of the men testified to having had at least one “walk” with Markland: James Pearson testified to having met Markland “several times,” while John Brown walked the public grounds and the city streets with the inspector general on multiple occasions.

As Markland walked with his male companions arms and shoulders were grasped, and hands were held. Most recalled having had both an affective and physical response to the touch of another man. As they recounted these intimate encounters with another man before the Executive Council, their reactions ranged from alarm to acquiescence.

John Brown was the first to testify. He explained that Markland had “laid his hand on my arm as if he knew me, and leaned on my arm. I was quite alarmed. I saw that he looked like a gentleman, and I did not understand his behaviour.” Brown’s response to Markland’s touch was to put his “other hand” upon his “bayonet and kept it there a while.” When they met again later that week Brown’s anxiety had been allayed. When Markland’s touch came, Brown took little notice.

A night or two afterwards, Mr. Markland met me again. He then laid his hand upon my left shoulder and walked with me in that position. He talked about where I came from, what regiment I belonged to, whether I would like to face McKenzie & other questions. He was of an indifferent nature. He walked with me down to the turn of York Street. And I went home to my quarters at the Lawyers Hall. We walked down toward the water and the Street in front of Mr. Markland’s house, past the Attorney General’s.

The public nature of this male intimacy is important, given that today many Canadian men avoid physical contact with other men that might be construed as sexual. Mark Greene identifies this as touch isolation and attributes it to the persistence of homophobia in modern society. Brown’s anxious understanding indicates that in 1838 he was aware that physical contact with another man could raise questions about his manhood and also quite possibly land him in jail. Yet Brown, like James Pearson, quickly became accustomed to the public touch of another man. Pearson reiterated in his testimony, for example, that “Mr. Markland never said any thing improper and never used any familiarity with me. He gave me much good advice.”

It was on the public boardwalk where, in 1833, Frederick Creighton Muttlebury first met Markland. Of the five men to testify none had spent as much time, in public or in private, with Markland. In fact, the duration and intimacy of Muttlebury and Markland’s relationship even prompted the Executive Council to inquire whether the law student resided at 28 Market Street (this was likely a veiled attempt at determining whether anything sexual might have taken place). “I have never resided at Mr. Markland’s,” clarified Muttlebury, “but I had a general invitation there, and was in the habit of dining with Mr. Markland about three times a week.”

Their relationship lasted for over a year, but in 1835, Muttlebury testified to having observed the inspector general’s “manner towards [him] gradually change.” Like Pearson and Brown, Muttlebury had initially found Markland’s “manner of taking my hand and keeping it in his own for several minutes” extraordinary, but came to accept it. When asked by the Executive Council about how often he and Markland held hands, Muttlebury ambiguously offered “when I would allow him.” Unlike the other men who testified to having been touched by Markland in public, Muttlebury recounted a time when Markland had—both in action and word—transgressed what the young lawyer understood to be the boundaries of proper manhood.

As the Executive Council pressed Muttlebury for details about the frequency with which he and Markland held hands, he offered the following account:

The first time he took my hand in this manner was in the street, where he held if for some time. I did not like it, but noticed the same thing on other occasions. On one occasion, I was dining with Mr. Markland alone when, I was much ashamed at Mr. Markland making the following observation, “do you know you have the most perfect fingers of anyone in town. Several people have remarked it.”

That night Muttlebury was troubled by Markland’s “habit” of same-sex intimacy and physical contact. It was also the night Muttlebury left 28 Market Street earlier than usual: “before ten.” While it is unclear whether it was a result of the private physical contact, Markland’s sexual advance, or because others in Toronto had been commenting on his physique, Muttlebury felt shame and sought advice from his male friends about the nature of his relationship with Markland. His testimony helps to historicize the parameters of socially and culturally acceptable contact between men.

Hand holding or arm touching in public and in private caused anxiety, but these were also physical and intimate boundaries men were willing to cross and, for the most part, felt comfortable with crossing. The touching of another man’s person was not a liberty men could take with one another, especially in a British colony where sodomy – a capital crime – could be deadly. So when the men who met Markland on the street, on the public grounds, or in his home asserted before the Executive Council that nothing improper had happened they implied not only that nothing sexual or criminal had happened, but also that they knew where to the draw the line. Despite having been touched by Markland their manhood remained intact.

Of all the men to testify before the secret inquiry that August, only Henry Stewart, a local Merchant who did not know Markland, provided hearsay evidence of the inspector general transgressing both the sexual and physical boundaries of proper manhood. Sodomy trials are known to have taken place across Upper Canada in this period; but this was not one and the same rules of evidence did not apply. So Stewart’s second hand account was documented. According to Henry Stewart, his younger brother John Stewart, had been sexually assaulted by Markland as they walked one evening toward the Garrison in Toronto’s west end.

That on the evening of Sunday he had met Mr. Markland, who asked him to walk with him. That they had walked up towards the Garrison. On the dusk of the evening that Mr. Markland had leaned upon his shoulder and had put his hand in an indecent manner on my brother’s person. And that he, my brother, immediately kicked Mr. Markland on the body and immediately ran away.

Henry’s account of John’s sexualized encounter with Markland is notable for its uniqueness. The sexual encounter took place in public (something none of the other men reported) and Markland took this action immediately (not after weeks or months of contact as Muttlebury’s testimony suggests). Moreover, in content and tone it shares much with an article published in the colonial press a week earlier that had also referred to the 1822 case of the Bishop of Clogher to describe Markland’s boundary crossing behavior. Yet such a sexually charged encounter was surely possible. And given that the inquiry ended abruptly with Stewart’s testimony on 7 August 1838, it appears that this was the sort of improper male touching that the Executive Council had hoped to uncover.

The testimonies of John Brown, James Pearson, Henry Hughes, Frederick Muttlebury, and Henry Stewart allow historians to grapple with the question of how men responded to intimate and physical contact with other men in early-Canada. As historians have shown for England, Australia, and America in this period, men who engaged in same-sex acts increasingly had their claims to manhood undermined. But the evidence gathered during the 1838 Markland inquiry also allows us to historicize men’s fears and anxieties about same-sex touch and intimacy—what we might identify as homophobia today—and how they came to understand certain types of male same-sex intimacy as improper and unmanly behaviour over the course of the nineteenth century.

Jarett Henderson is as Associate Professor of History at Mount Royal University (Calgary, Alberta, Canada) where he teaches Canadian and colonial history in the Department of Humanities. His current research explores the relationship between same-sexuality and settler self-government in 1830s British North America, and how that history was linked to larger, empire-wide debates, about freedom, liberty, and colonial rule.

Jarett Henderson is as Associate Professor of History at Mount Royal University (Calgary, Alberta, Canada) where he teaches Canadian and colonial history in the Department of Humanities. His current research explores the relationship between same-sexuality and settler self-government in 1830s British North America, and how that history was linked to larger, empire-wide debates, about freedom, liberty, and colonial rule.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com

I enjoyed reading this interesting post, but wondered how romantic friendships could map onto Markland’s interactions with other men. I appreciate that most of the encounters you describe were seemingly spontaneous and public, but it seems that his relationship with Muttlebury was ongoing. And whether or not we can understand any of Markland’s contact with other men in this way, I’d like to know more about whether men in colonial Canada could have understood their interactions in this way. Is same-sex romantic friendship a useful way of understanding some relationships between men (and women) in colonial Canada, or are there reasons why this might not apply there?