With the passing of Hugh Hefner on September 27, 2017 at the age of 91, his larger than life persona and controversial lifestyle are once again matters of serious and polarizing debate. He was, for better or worse, an important force in post-war sexual history and a figurehead in public conversations about morality, sexuality, and pornography for nearly seventy years. Before founding Playboy, Hefner acted as an editor-in-chief for one issue of a humor magazine, Shaft, that documents his first foray into commercializing sex.

Shaft, a humor magazine published at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign from 1946 through 1955, is filled with satires of campus life, sexual humor, and advertisements for local bars. This was standard for college humor magazines. Still, it provides fascinating insights into the changing sexual and gender norms on campuses after World War II. Beth Bailey found that conflicts over changing sexual mores were not limited to the coasts, nor were they entirely the result of radical voices or famous personalities. The February 1948 issue of Shaft speaks to both the shifts in sexuality and gender norms amongst Midwestern college students and the rise of Hugh Hefner and Playboy, often portrayed as the vanguards of the “Sexual Revolution.”

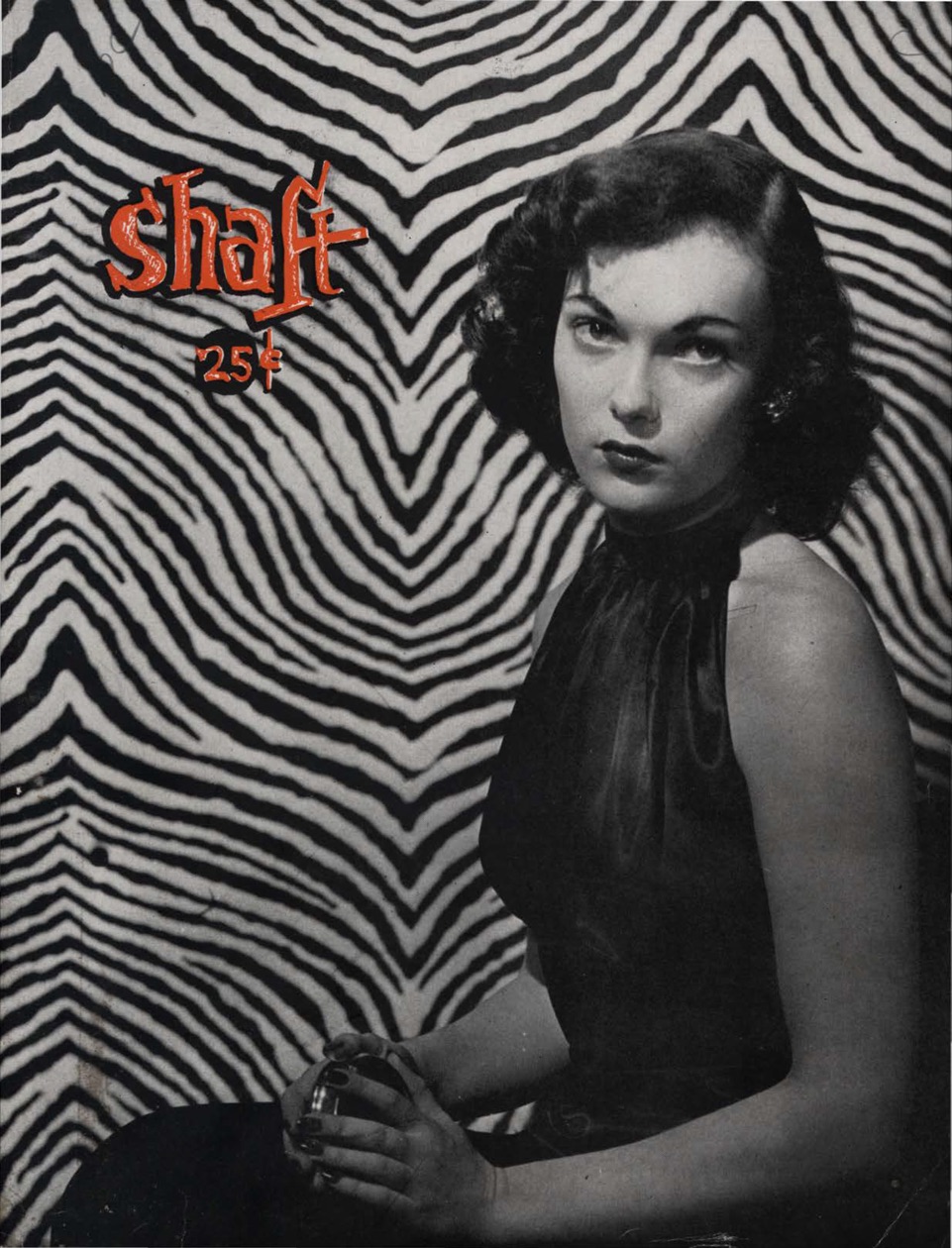

At first glance the magazine looks like a homemade Playboy: a young woman in a silky top sitting before a flashy zebra-print background. That’s exactly what Shaft was, a Playboy prototype, created by the magazine’s then editor, Hefner. A journalism and psychology major with dreams of becoming a cartoonist, Hefner drew previous Shaft covers, cartoons for the student newspaper, The Daily Illini, as well as the earliest issues of Playboy. This issue of Shaft, which he referred to as “this journalistic abortion,” was his only outing as editor-in-chief of Shaft (and only magazine editorial position prior to Playboy). It was Hefner’s first attempt at commodifying sex and the male gaze in print. Many of the themes Hefner expanded upon in Shaft are found in his contemporaneous cartoons in The Daily Illini.

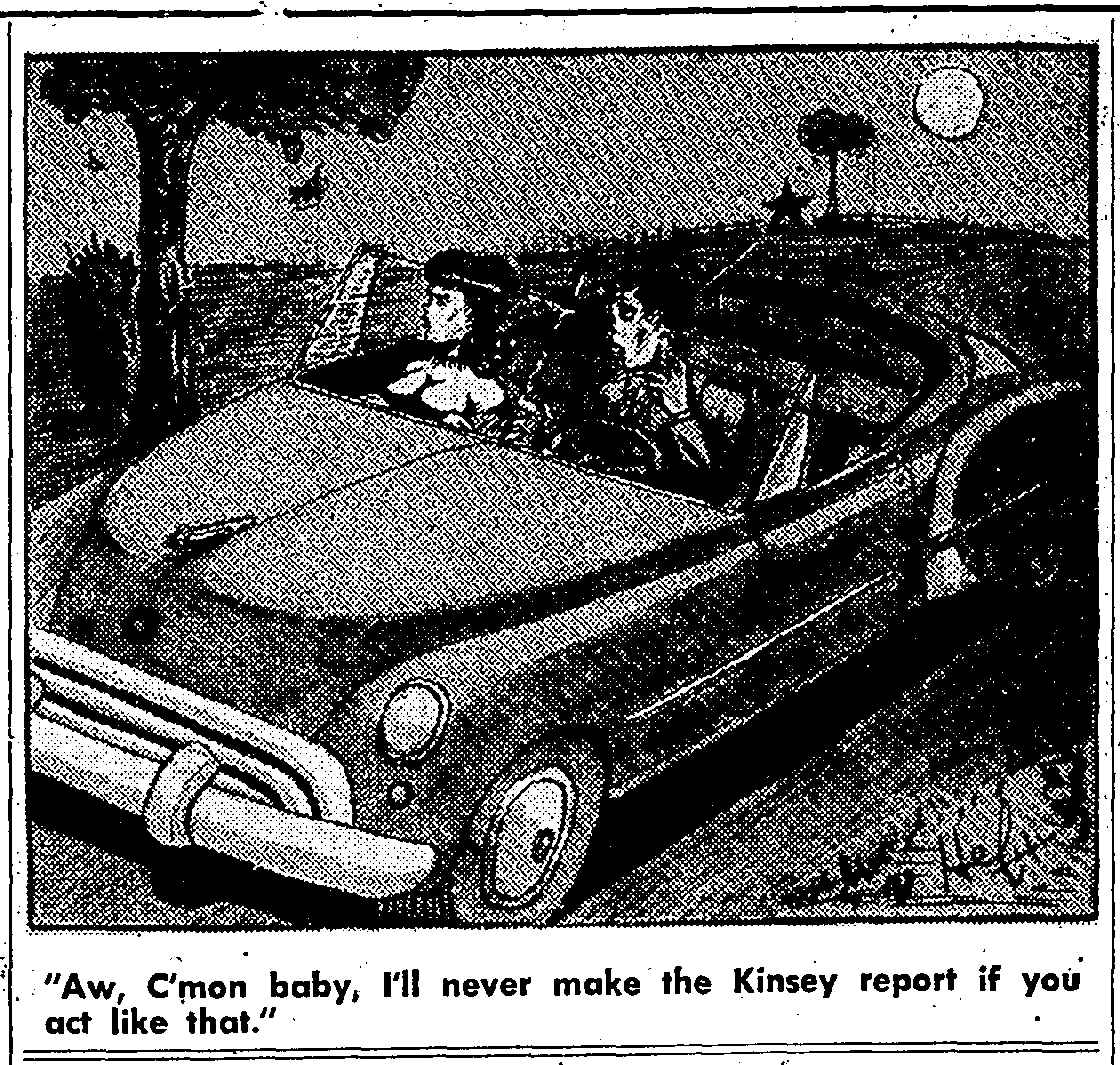

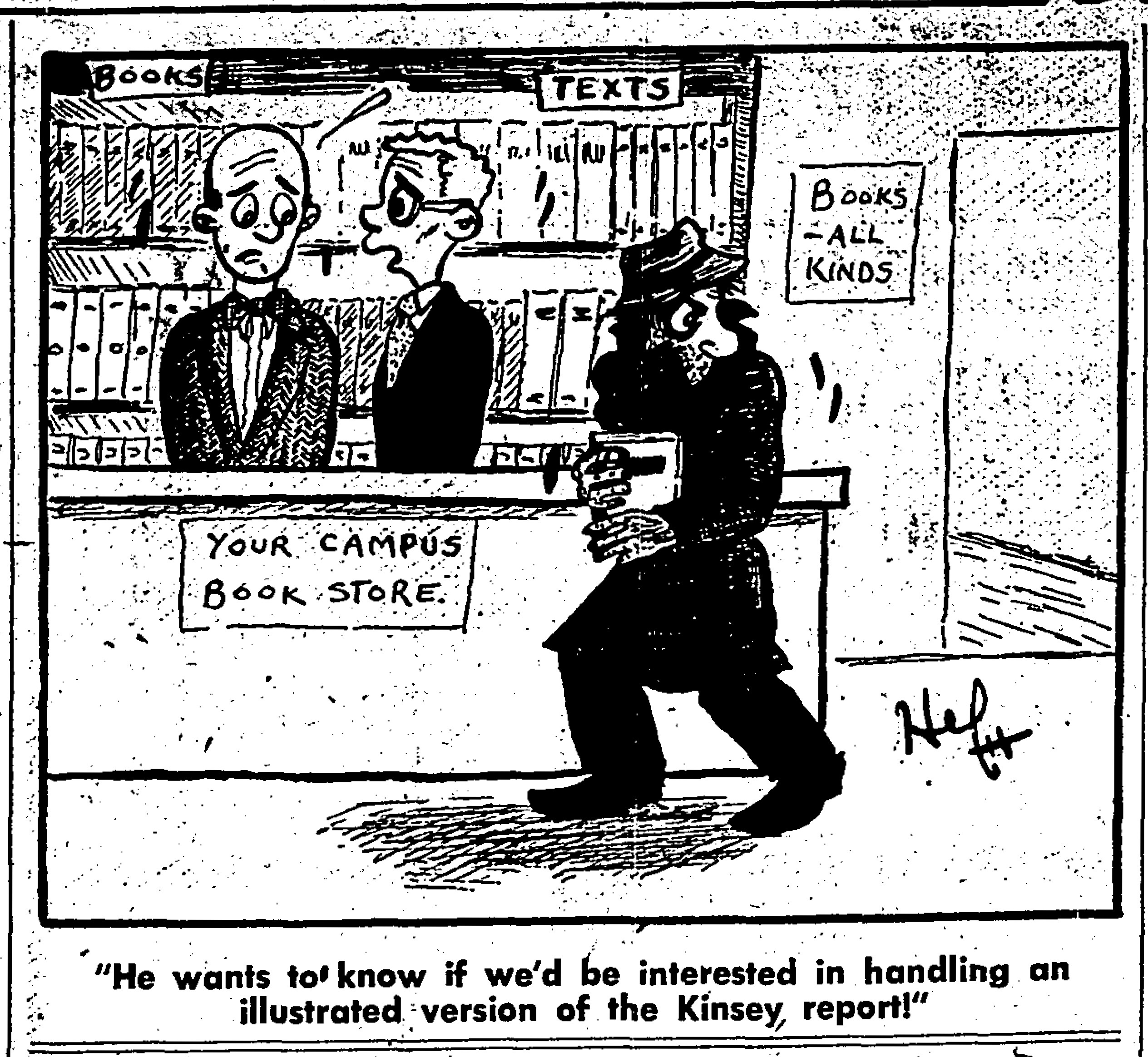

One of the cartoons, set at a rural necking spot, flouts the university’s rules against promiscuity and automobile ownership (students were banned from owning cars until 1953). Another Hefner cartoon depicts a trench-coated pornographer trying to interest the campus bookstore in illustrated editions of Alfred Kinsey’s works.

Hefner reviewed Kinsey’s male study in a column titled, Ces martyrs: le fous d’Amérique. (These Martyrs: The Madman of America). He found it an interesting read but, “Dr. Kinsey’s book disturbs me.”

Not because I consider the American people overily [sic] immoral, but this study makes obvious the lack of understanding and realistic thinking that have gone into the formation of our sex standards and laws. Our moral pretenses, our hypocrisy on matters of sex have led to uncalcuable [sic] frustration, delinquency and unhappiness.

Hefner’s challenge is not to Kinsey’s study, but the sexual hang-ups and restrictive attitude of American sexuality at the time. In 1948, Hefner already recognized a moral and legal landscape in need of disruption.

“While I’m on the subject of sex (and I usually am),” Hefner continued to argue that Shaft could not publish a “Sex Issue” because “every issue of Shaft is a sex issue.” His frequent commentaries on sexuality were forays into the smoking-jacketed persona he later perfected and marketed in Playboy. A poorer version of this bachelor appears in Shaft. Lacking the capital of a successful urbanite, the college bachelor was locked in a cycle only allowing for sumptuous meals, cigarettes, and dating when his paycheck, or stipend from home, arrived.

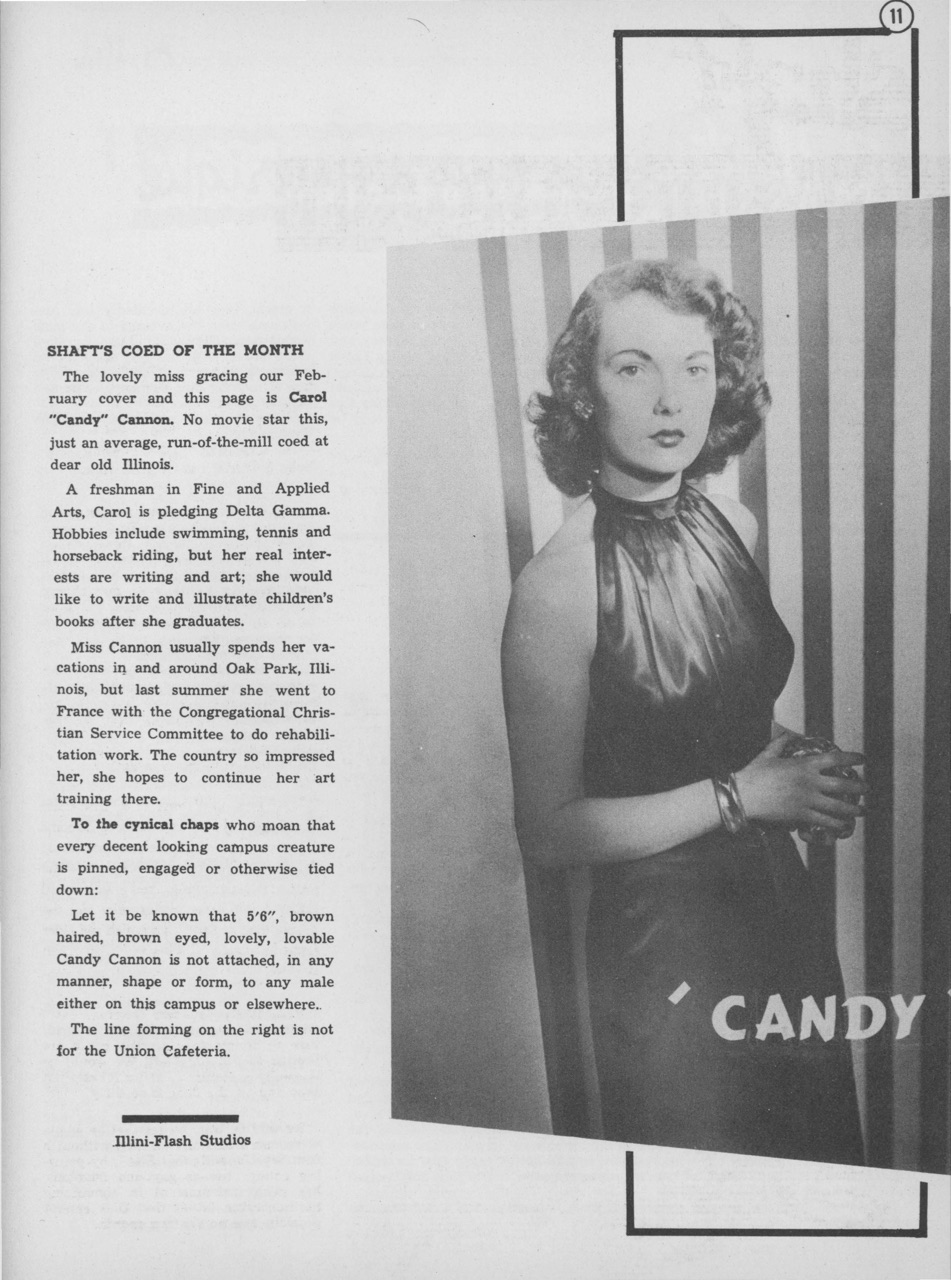

Hefner’s addition of a coed spread foreshadowed the centerfold, but more immediately it targeted the male gaze on campus at Carol “Candy” Cannon, “just an average, run-of-the-mill coed at dear old Illinois.” Hefner framed Carol as the girl next-door. She was an upstanding freshman student, a member of the Congregational Church, and active in sorority and athletic activities. All these traits led to a singular conclusion in Hefner’s article – she’s single and available. “Let it be known that 5’6’’, brown haired, brown eyed, lovely, lovable Candy Cannon is not attached in any manner, shape or form, to any male either on this campus or elsewhere.” By agreeing to pose for the magazine, readers were to infer that Carol’s wholesome demeanor complimented her sexual openness, a logical jump still endemic in rape culture.

Other signs of the direction of Playboy are found in Hefner’s issue of Shaft. An interview with a long-haired male student critiques masculine norms and muddles the gender binary, “Both Dave and his petite wife, Monica, get a kick out of being long hairs.” An advertisement for an Urbana dive bar, “Bunny’s” features coy pairs of bunnies hopping off for a drink. Although Hefner did not draw this advertisement, this bar did lend its name to Playboy’s logo and female employees according to a letter from Hefner hanging behind the bar today.

Hefner’s cartoons and Shaft work speak to negotiations and negations of sexual norms undertaken by students. Necking spots, motel trysts, the Kinsey report, and coed pictorial challenged conservative norms while simultaneously reifying male dominance and female objectification. Critically reading Shaft expands the history of the most well known men’s magazine and pornographic publication in the nation (if not the world). Moreover, seeing Playboy as more than a vehicle for urbane white male consumption, but rather as a publication that began rooted in a struggle with restrictive rural values, challenges our assumptions about the sites of sexual change.

Nathan Tye is a doctoral candidate in History at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. His dissertation, “The Ways of the Hobo: Transient Mobility and Culture in the United States, 1890s-1950s,” charts the intersections of gender, sexuality, and mobility in hobo communities in the United States. This piece is part of a course, Gender, Crime, and Civil Disobedience on Campus: A History of the University of Illinois, he co-teaches as part of the University’s 150th anniversary commemorations of 2017. He tweets from @Hobo_History.

Nathan Tye is a doctoral candidate in History at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. His dissertation, “The Ways of the Hobo: Transient Mobility and Culture in the United States, 1890s-1950s,” charts the intersections of gender, sexuality, and mobility in hobo communities in the United States. This piece is part of a course, Gender, Crime, and Civil Disobedience on Campus: A History of the University of Illinois, he co-teaches as part of the University’s 150th anniversary commemorations of 2017. He tweets from @Hobo_History.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com

I just want to say that Carol “Candy”Cannon is my mother. She past away quite a few years ago, but Googling her name was heart warming!