Rebecca Jennings

Lesbians found it very difficult to make sense of their sexuality, to find partners and to express desire in mid-twentieth-century Australia due to negative social attitudes. This is reflected in the historical literature on lesbianism that is largely silent on the issue of lesbian sex. However, oral history interviews conducted for my current project on lesbian relationships in post-war Australia, together with other personal accounts, ephemera and lesbian and feminist literature, provide a picture of shifting assumptions and practices of lesbian sex since the Second World War. Concepts of lesbianism were formed in a context of widespread cultural silence: newspapers avoided the topic, strict censorship laws prevented the publication or importing of books on homosexuality, and lesbianism was taboo in general conversation before the late 1970s. In the absence of informed discussion, post-war stereotypes typically assumed lesbians to be highly-sexed curiosities. Oral history interviews and archival sources reveal that typecasts of the hyper-sexed lesbian inhibited some women from expressing their sexual desires. Others within some lesbian communities followed very prescriptive ideas of appropriate sexual practice with their partners.

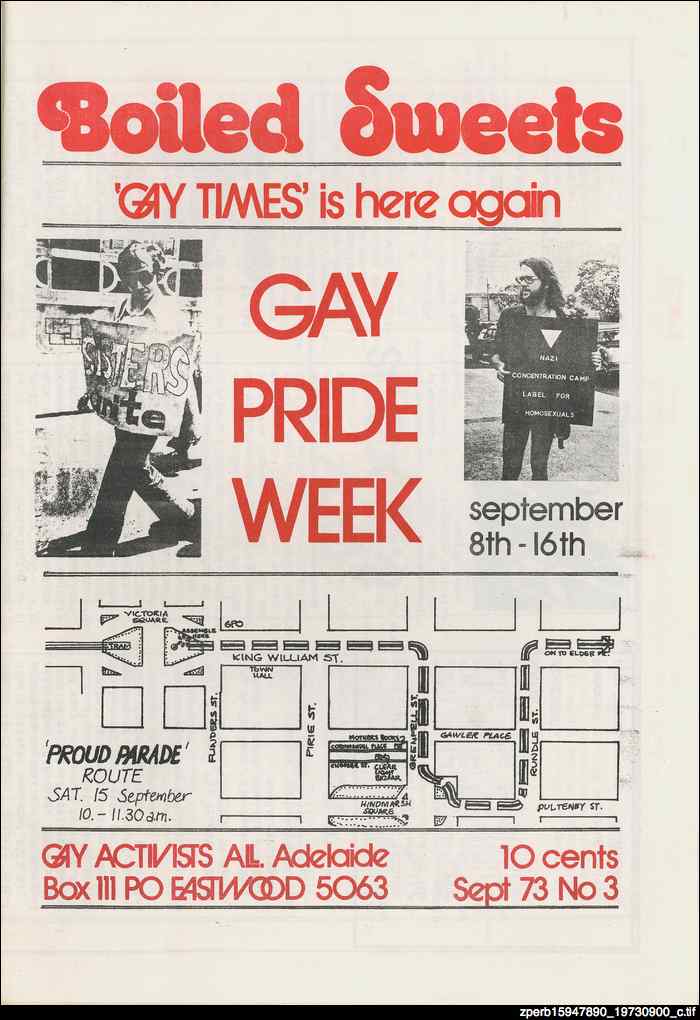

In the 1950s and 1960s, medical opinions on lesbianism (such as there were) typically portrayed women as promiscuous individuals who engaged in bizarre sexual acts. Psychiatric commentaries described lesbian sexual encounters with the purpose of seeking a cure, downplaying or ignoring the emotional and social aspects of female-only relationships. Some medical practitioners associated lesbian sex with the use of dildos and other sex toys, assuming a penetrative model of sexuality. In 1973 one lesbian feminist wrote to Boiled Sweets, the newsletter of Adelaide’s Gay Activist Alliance, describing the prejudices and misconceptions exhibited by a gynaecologist she had recently consulted. ‘He was surprised to learn that few lesbians use dildos’, she wrote. Popular culture also peddled misinformation about lesbians. John B. Murray’s 1970 documentary film survey of Australian sexual attitudes, The Naked Bunyip, for instance, portrayed the sexual lesbian as promiscuous. The film edited interviews with the central lesbian character in order to emphasise her frequent casual sexual encounters.

Stereotypes impacted on some lesbians’ attitudes toward sex, making them reluctant to identify as lesbian or act on sexual desires for women. My interview with Margaret illustrates this point. A Sydneysider born in the 1920s, Margaret had her first affair with another woman on board a ship to Europe in the 1950s. She lacked the language to name her new sexual self but recalled assuming that the woman who had seduced her was ‘deviant [and] over-sexed’. Another Sydney lesbian, Sandra, born a decade later, also described in her memoir her fears that her sexual partners would consider her excessively interested in sex. She felt inhibited in expressing her sexual desires – even in private – and felt that this impacted negatively on her relationships. Recalling visits from two lovers in the mid-1950s, Sandra explained:

I was fearful to show just how anxious I was to touch and kiss, lest others deem me a sex maniac of sorts. I was fearful to show any emotion at all. But as emotion was constantly raging through me, my attempts at repression were most painful. And incomplete. So I remained a tense, stiff, hurting individual who could bring no pleasure to others.

Lesbian subcultures and communities were particularly important for women to make sense of and act upon their same-sex desires given negative social attitudes. Women connected to lesbian communities in this period describe having a very clear sense of the forms of sexual practice expected by their partners and the wider community. Butch/femme subcultures in the 1950s and 1960s allowed women to articulate their erotic inclinations within strict behavioural codes. Butch lesbians were expected to adopt active sexual roles, giving sexual pleasure to their femme partners but not receiving active stimulation in return. These subcultural expectations created a unique form of sexual practice among many Australian women. According to Melbourne lesbian Marion:

It was not all right for a butch to be touched sexually and it is only recently that I’ve been able to be touched and I sometimes feel awkward about that. Do not assume that this has meant that my sex life has ever been anything but amazing and wonderful! I have always had a strong sex drive and I’ve shared that with some great women. And learning to be touched hasn’t made sex ‘better,’ only different.

Karen, a Sydney butch lesbian, gives a more explicit account of acceptable butch sexual practices in the 1960s.

I would be on top I would perhaps put my breast in her mouth and as I stimulated her I would rub myself off on her leg or I learned how to have an orgasm by the pleasure of the woman I was pleasuring. Without stimulation … And of course knowing that I was giving pleasure was giving pleasure to me.

Some communities strictly policed the expectation that butch partners would take an active role in sex through gossip, bullying or ostracism of women who failed to conform. But many women like Marion remembered butch/femme sexual practice as erotic and enjoyable and found the clear expectations reassuring in a hostile society.

In the early 1970s, the women’s movement offered an alternative space in which women attracted to other women could explore their sexual identities and act on their desires. Feminist sexual politics critiqued penetrative sex as an invasion of the female body and an act of subordination. It celebrated the clitoris as the locus of sexual pleasure for women. Lesbian feminist sex was framed in feminist journals and literature as potentially much more equal than the active/passive roles which feminists considered to be central to both heterosexual and butch/femme sex. Reflecting on her journey from heterosexual feminist to lesbian feminist, Sue told Sydney Women’s Liberation Newsletter in October 1975:

I guess the basic attraction for me in being sexually involved with women was that I felt that it would entail total involvement. Unlike with men, with women I felt that I wouldn’t be able to just lie back and take it. There wouldn’t be a hierarchy automatically established by our sexes. There is no lesbian equivalent of the missionary position!

The ‘total involvement’ Sue imagined arose from the unique friendship and intimacy women experienced with each other and the social equality which existed between two women. Jan, a lesbian feminist, echoed Sue’s sentiment in another feminist circular of the early 1970s, arguing that women’s innately nurturing and creative qualities made them inherently superior lovers. She claimed: ‘Women are more tender, more sensitive and considerate of the feelings of others, and while this may be due to our conditioning it makes for a better lover.’ These qualities also suggested an instinctive element to female-only love. As Marilyn put it in a letter to Lesbian Newsletter in September 1977, ‘Lesbian love needs no “practice” in its sexual aspects, coming naturally and spontaneously. It cares for oneself and the other woman one is in a loving relationship with.’

This idea of ‘natural’ and equal sex also prompted a rejection of the sex toys seen as so central to lesbian sexual practices by post-war psychiatrists. Sylvia, who was involved in lesbian feminist communities in Adelaide in the 1970s, complained in an interview with me:

Relationships were supposed to be very respectful, very vanilla, if you like to put those phrases on it … no violence, no aggression. It was even hard to talk about (I did this and got a little bit of flack) vibrators – [they] were a bit iffy, let alone dildos. Right? So lesbians, whether they did it or not, there was certainly no one would’ve admitted strapping on a dildo – my God, so awful.

Some women found lesbian feminist sexual culture to be exciting and full of possibilities. Recalling her sexual encounters in lesbian separatist communities in the late 1970s, Laurene commented: ‘That was before the notion you had to have toys or anything like that. It was just passion and intensity, I guess, is my experience. I can’t say that’s everyone’s, eh? But I’ll tell you it was mine. I had some fabulous sex!’

Historic and contemporary taboos surrounding lesbian sex make it difficult for historians to document the diversity of lesbian sexual practice in post-war Australia, as elsewhere. But despite negative social attitudes, lesbians found new ways to express their desires for other women, whether butch or femme, non-penetrative, feminist, separatist or, like many intimate experiences, a complex mix of practices and behaviours.

Rebecca Jennings teaches the history of gender and sexuality in modern Britain in the Department of History at University College London. She has published widely on Australian and British lesbian history and her most recent book, Unnamed Desires: A Sydney Lesbian History was published by Monash University Publishing in 2015 and shortlisted for the NSW Premiers History Award 2016. She is currently working on a new monograph, Sisters, Lovers, Wives and Mothers: Lesbian Practices of Intimacy in Britain and Australia, 1945-2000, based on her Australian Research Council-funded research into post-war British and Australian lesbian relationships and parenting.

Rebecca Jennings teaches the history of gender and sexuality in modern Britain in the Department of History at University College London. She has published widely on Australian and British lesbian history and her most recent book, Unnamed Desires: A Sydney Lesbian History was published by Monash University Publishing in 2015 and shortlisted for the NSW Premiers History Award 2016. She is currently working on a new monograph, Sisters, Lovers, Wives and Mothers: Lesbian Practices of Intimacy in Britain and Australia, 1945-2000, based on her Australian Research Council-funded research into post-war British and Australian lesbian relationships and parenting.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com