Jana Funke

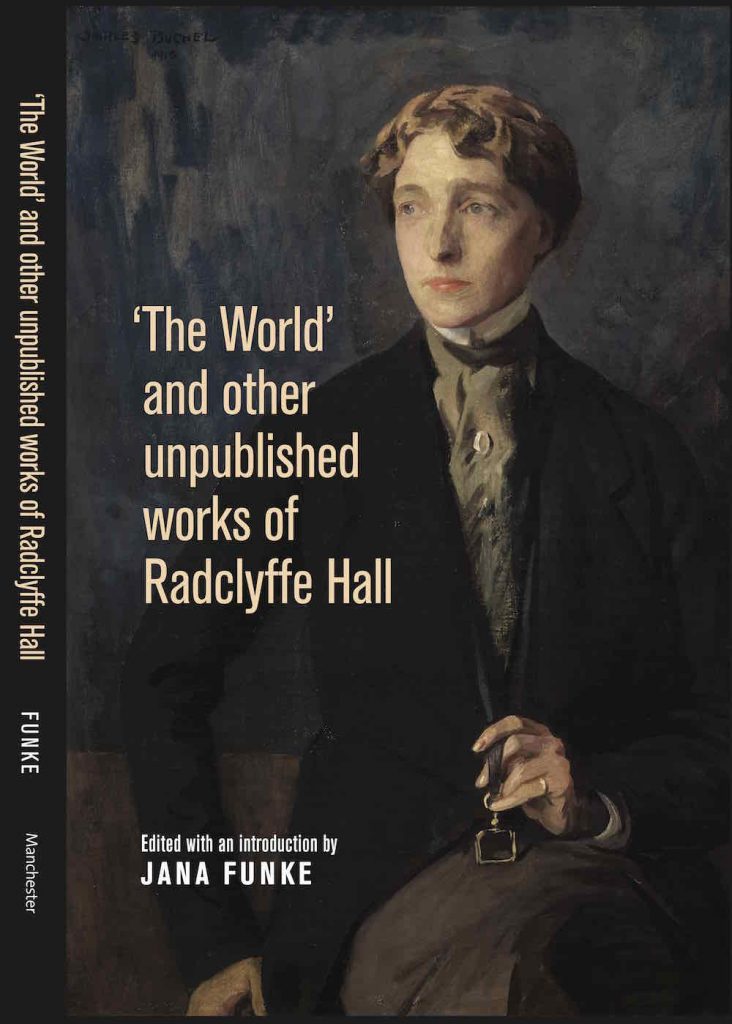

90 years ago this month, on 27th July 1928, Radclyffe Hall’s novel The Well of Loneliness was first published in the UK. The book was banned as obscene in Britain due to its lesbian content. A volume of previously unpublished works by Radclyffe Hall, edited and introduced by Jana Funke, opens up new perspectives on the author.

NOTCHES: In a few sentences, what is your book about? Why will people want to read your book?

Funke: My book presents a wide range of previously unpublished works by early twentieth-century author Radclyffe Hall. Most historians of sexuality and literary scholars know Radclyffe Hall as the author of The Well of Loneliness (1928), a novel that played a key role in shaping understandings of lesbian and trans identities and inspiring debate about censorship and freedom of expression.

My edition of Hall’s archival materials complicates existing readings of The Well of Loneliness: I have included a newly transcribed draft of the war section of the novel, which is surprising in many ways. The earlier draft is more explicit in its depiction of lesbian sexuality than The Well of Loneliness and more celebratory about the protagonist’s gender nonconformity, which Hall here presents as highly attractive and seductive. I believe Hall rewrote these sections before publication, because she knew that presenting lesbian sexuality and gender variance in an affirmative light would make the book even more scandalous. Readers who complain that the novel is too miserable and depressive need to keep this in mind: Hall knew the risks involved in publishing this book and she tried to make it more palatable to the British public.

But what was particularly important to me in putting together the book is that it also takes us far beyond Hall’s most famous novel. Before she wrote The Well of Loneliness, she was a successful and popular author, who wrote about a wide range of topical issues. Researching in the archives reminded me that Hall’s work was much more diverse than we tend to acknowledge today. For instance, she was interested in all aspects of gender and sexuality beyond those explored in The Well of Loneliness. The unfinished novel The World, and many of the short stories included in my volume, for instance, explore heterosexual relations and the ways in which heterosexual people navigate gender roles. So, the book will be of interest to anyone keen to learn more about Hall, debates about diverse genders and sexualities in the interwar period, and early twentieth-century literature and culture more generally.

NOTCHES: What drew you to this topic, and what are the questions you still have?

Funke: Part of my motivation was personal: I first read The Well of Loneliness when I was 16 years old and loved it. Hall was also one of the authors I wrote about in my PhD, and during that time I began to sense that scholarship had often viewed her too narrowly, focusing mainly on The Well of Loneliness. These suspicions were confirmed when I visited the Harry Ransom Centre in Austin, Texas, after being awarded a Hobby Family Foundation Fellowship to conduct research on the Radclyffe Hall and Una Troubridge Papers.

Even though I worked in the archive for months and on the book for years, I still have a lot of questions: it is not clear to me why Hall did not publish some of the texts included in this volume. Reading earlier drafts of published materials, you also wonder why the author made certain decisions. I am also keen to do more work on Una Troubridge, Hall’s life-long partner. Having spent so much time trying to decipher Hall’s illegible hand-writing, transcribing and editing her drafts, I feel a real connection with Troubridge, who did the same work in the past. Her role as Hall’s collaborator has not yet been fully acknowledged.

NOTCHES: This book is about the history of sex and sexuality, but what other themes does it speak to?

Funke: Thinking about Hall as an author exclusively or even primarily preoccupied with lesbian relations or a specific model of gender nonconformity really does not do justice to the diversity of her literary output. The archive demonstrates this, as I argue in my introduction to the book. Hall wrote about race relations, national politics, class dynamics, bonds between humans and animals, as well as religious, supernatural and mystical experiences, to name but a few topics. Gender and sexuality are often intertwined with these issues, of course, but we need to go beyond reading all of her work only for hints or traces of lesbian desire, because this means missing out on all the other topics she sought to explore in her writing.

NOTCHES: How did you research the book? (What sources did you use, were there any especially exciting discoveries, or any particular challenges, etc.?)

Funke: Some of the immediate problems were related to transcribing and editing the archival material at the Harry Ransom Centre. As I said above, Hall’s handwriting and spelling are a real challenge. Another issue was deciding which materials to include: I tried to strike a balance between publishing materials that would enrich areas of Hall’s work that were already of interest to scholars and including texts that would push our understanding of Hall in new directions.

I also came across materials that were horrible to read and challenging for that reason: for instance, Hall’s short story “Mark Anthony Breaks” is shockingly racist, at least by our standards today. I did a lot of research for my introduction and sought to situate the story in its historical context. This revealed that Hall was, in fact, engaging with ideas that were presented as progressive by some African-American leaders at the time, specifically Booker T. Washington. However, I did not want to find excuses for Hall’s racism nor did I want to try and sanitise her image by excluding the story from the book. But I was aware that it would shape the way people think about her, and it was not an easy decision to include it.

NOTCHES: Whose stories or what topics were left out of your book and why? What would you include had you been able to?

Funke: The Radclyffe Hall and Una Troubridge Papers at the Harry Ransom Centre are extensive, and there is far too much material for a single book. Had I had more space, I would have liked to include some of the other short stories or some of the autobiographical essays and fragments. There are also wonderful letters that readers sent to Hall after The Well of Loneliness trials, telling her how the novel changed their views on female homosexuality or allowed them to identify with the protagonist. I can only imagine how meaningful these letters were for Hall and Troubridge.

NOTCHES: Did the book shift significantly from the time you first conceptualized it?

Funke: Working on a literary archive, even a well-catalogued one, is always a journey of discovery, and you rarely find what you expect. For instance, I was surprised that Hall did not engage more with sexological ideas – I am interested in the relation between literature and sexual science, so this is what I was initially looking for when visiting the archive. So much emphasis has been put on the ways in which Hall uses the sexological terminology of ‘sexual inversion’ in The Well of Loneliness that I was expecting an archive full of sexual scientific references. What I did find were writings that reveal how someone like Hall, who did have access to sexological ideas at a time when these were not widely circulated, negotiated and combined sexual scientific terminologies and frameworks with other forms of knowledge, including religion or spirituality. And sometimes she chose not to engage with sexual science at all! This reminded me that we need to be aware of the diverse forms of knowledge that people can draw on – often in idiosyncratic and unexpected ways – to make sense of their own experiences or to construct fictional depictions of sexuality and gender in literary works.

NOTCHES: How do you see your book being most effectively used in the classroom? What would you assign it with?

Funke: The book can be used in a number of different ways in the classroom: the early drafts of The Well of Loneliness would be interesting to read alongside newspaper reports and legal document from the censorship trial. A text like The World would be fascinating to teach in a class on masculinity and heterosexuality in the interwar period, perhaps alongside marital advice literature from the late 1910s and early 1920s. And much of the short fiction dealing with supernatural or mystical experiences could be paired with sources about psychic research or theosophical debates in the early twentieth century. These are just a few possibilities. I have had a chance to teach some of the materials included in my book and found that it is really freeing for students to work with archival sources that not a lot of people have read or written about before. There is real scope for new approaches and original thought.

NOTCHES: Why does this history matter today?

Funke: There is a surge of interest in Hall’s work. I am excited to be part of a new moment in Hall scholarship – I am thinking of recent research by Richard Dellamora, Elizabeth English, Steven MacNamara and Hannah Roche, for instance – that has and will continue to open up vital new insights into her life and work. But Hall also matters beyond academic circles, as she is often remembered as an LGBT pioneer. In this context, I am particularly interested in debates about whether Hall should be read as a lesbian woman or a trans man. I tend to write and talk about Hall using female pronouns, because this is what she and those closest to her chose to do. However, I encourage reading Hall as an individual who is also part of trans history – she called herself ‘John’ and clearly identified as masculine. For this reason, Hall’s life offers an important opportunity to think about the fact that lesbian and trans histories can be entangled in complex ways. This is something we should acknowledge, celebrate and use to challenge false antagonisms a few people want to create between lesbian and trans communities. Being lesbian or trans are not the same, but Hall’s life and some of her work demonstrate that there is a shared history.

NOTCHES: Your book is published, what next?

Funke: I am not done with Hall yet! I am co-organising, together with Elizabeth English and Sarah Parker, a symposium to mark the 90-year anniversary of the publication of The Well of Loneliness this summer. I am also finishing a book on early twentieth-century women’s writing and sexual science, and Hall as well as Troubridge feature in it. Having written a lot about Hall, I am excited to use this opportunity to situate her work as well as that of Troubridge among much wider networks of exchange and dialogue to demonstrate the far-reaching connections between modernist literature and sexual science.

Jana Funke is Senior Lecturer in English and Medical Humanities at the University of Exeter. She has published journal articles and book chapters on modernist literature, the history of sexual science, and the history of sexuality. Books include Sex, Gender and Time in Fiction and Culture (co-edited with Ben Davies, Palgrave, 2011), The World and Other Unpublished Works of Radclyffe Hall (MUP, 2016) and Sculpture, Sexuality and History: Encounters in Literature, Culture and the Arts from the Eighteenth Century to the Present (co-edited with Jen Grove, Palgrave, 2018). In 2015-2016, Jana was selected to participate in the New Generations in Medical Humanities programme, funded by the AHRC and the Wellcome Trust. In 2015, she was awarded a Joint Investigator Award (with Kate Fisher) by the Wellcome Trust to lead a five-year project on the cross-disciplinary history of sexual science called Rethinking Sexology.

Jana Funke is Senior Lecturer in English and Medical Humanities at the University of Exeter. She has published journal articles and book chapters on modernist literature, the history of sexual science, and the history of sexuality. Books include Sex, Gender and Time in Fiction and Culture (co-edited with Ben Davies, Palgrave, 2011), The World and Other Unpublished Works of Radclyffe Hall (MUP, 2016) and Sculpture, Sexuality and History: Encounters in Literature, Culture and the Arts from the Eighteenth Century to the Present (co-edited with Jen Grove, Palgrave, 2018). In 2015-2016, Jana was selected to participate in the New Generations in Medical Humanities programme, funded by the AHRC and the Wellcome Trust. In 2015, she was awarded a Joint Investigator Award (with Kate Fisher) by the Wellcome Trust to lead a five-year project on the cross-disciplinary history of sexual science called Rethinking Sexology.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com