Hongwei Bao

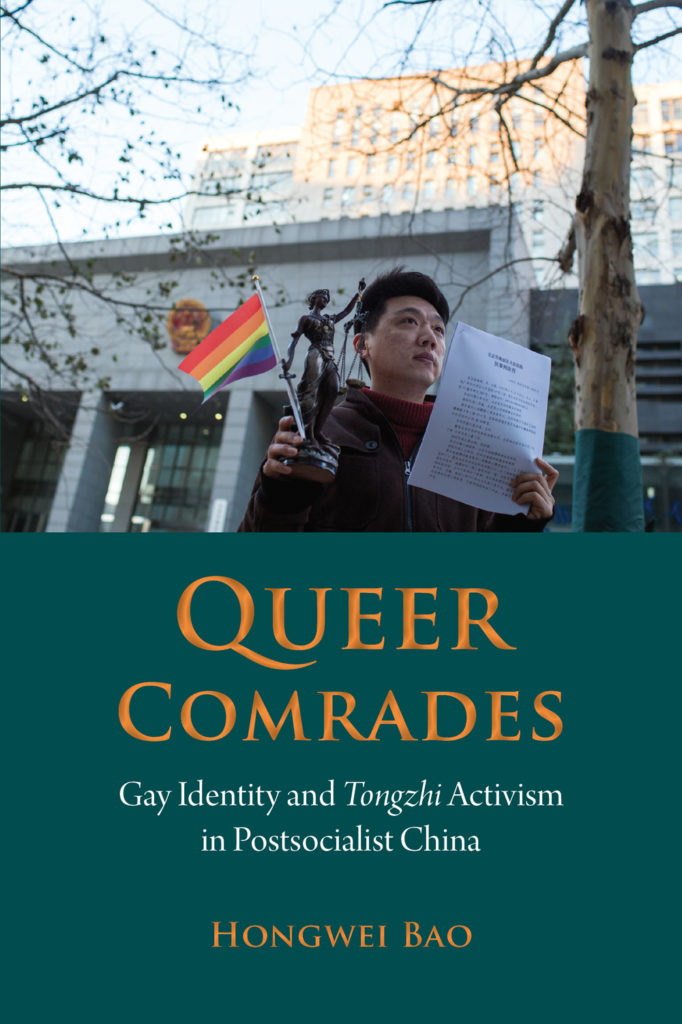

Queer Comrades is about the emergence of a specific type of gay identity, tongzhi (literally ‘comrade’), in China’s post-Mao era (1978 to present), as well as its associated forms of queer activism. Although undoubtedly influenced by transnational capitalism and the global LGBTQ movement, the tongzhi identity is also shaped by China’s socialist past and postsocialist present. This book places queer identities in China (including but not limited to tongzhi) in historical, social and cultural contexts and examines how they are produced by, and at the same time have impact on, China’s history and society.

NOTCHES: What drew you to the topic, and what are the questions you still have?

Hongwei Bao: When I left China for Australia to undertake my PhD ten years ago, queer culture in China was fast developing, with bars, clubs, community events and LGBT organisations mushrooming all the time. However, in the international news media, queer culture in China was often reduced to a simplistic ‘repressive hypothesis’ narrative: gay people were ‘suffering’ in China. Having lived in China for about thirty years and having witnessed some of Beijing’s queer community organising, I felt that this was an important historical period for China’s queer history, and it was worth documenting. As a PhD student of gender studies and cultural studies, and with connections to Beijing’s queer communities, I was in a good position to document this history. I decided to devote my PhD thesis to a study of queer culture in China.

I still have many questions, however, and I do not think that they can be resolved soon. One of them is how the Chinese contexts impact on gay identity and queer activism, and where indigenous agency lies. My work overall has tried to answer these questions in different ways. In my book, I have highlighted the importance of China’s socialist past in shaping contemporary gay identity and queer activism. But historical studies of Maoist sexualities are still scant, and they often give fragmented and contradictory information about the era. Fortunately, queer historians including Wenqing Kang have been conducting oral histories with older gay men who experienced the Maoist era, and their research will be able to shed more light on the ‘forgotten’ experiences in that era.

NOTCHES: This book is clearly about sex and sexuality, but what are other themes it speaks to?

HB: One of the key themes of this book is the political mediation of sexuality. Sex and sexuality are situated in complex configurations of power; they are often used for political control, for effective management of population, and for demarcating normalcy from deviance. For example, the emergence of gay identity and non-heteronormative sexualities in postsocialist China marks the hegemony of a new governing regime and rationality, which is often known as neoliberalism, in the postsocialist era. However, this does not mean that we should be pessimistic: sex and sexuality can also be used by marginalised groups, by queer people, as ‘counter-discourses’, to empower themselves and fight for their rights. The burgeoning queer activism in contemporary China in the last two decades is a good example. Throughout my book, I have tried to demonstrate that although sex and sexuality constitute part of the new governing regime, they can also be used politically for anti-hegemonic purposes in our times.

NOTCHES: How did you research the book?

HB: I started this project by delving into historical archives, media coverage, and queer cultural texts, including queer fiction and films. In the process, I discovered ‘conversion therapy’ diaries: the diaries written by gay people who received medical treatment in order to turn straight in the 1980s and 90s.

I soon found the text-focused approach insufficient, so I went to China and conducted fieldwork in queer communities in three Chinese cities: Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou. The bulk of this project’s fieldwork took place between 2007 and 2009, but I have constantly revisited my fieldwork sites and met my interlocutors several times in the past ten years. The fieldwork really opened my eyes: I experienced the rapid development of queer culture at the beginning of the twenty-first century, when the queer communities were still in their stage of formation and when there seemed endless optimism and creative energy in the communities. I was fortunate to have met a lot of fantastic queer individuals and organisations who generously helped my research. I was also lucky to be part of the Beijing Queer Film Festival and China Queer Film Festival Tour. It was an exciting time, and no one could have foreseen that this was about to change, and queer activism would be subject to stricter government censorship and control in the second decade of this century.

In retrospect, my fieldwork captured a specific historical moment when the political economy of China shaped gay identity and queer activism in specific ways since China’s entry into the World Trade Organisation in 2001. There was loosening control of queer culture by the government as part of the liberalisation, deregulation and commercialisation processes after China’s WTO entry. There was also generous provision of national and international funding as a result of the global campaign of fighting HIV/AIDS, which facilitated the establishment of queer grassroots organisations all over the country. The HIV/AIDS funding and the development of a pink economy have complex ramifications for queer culture today.

My archive thus comprises of historical documents, queer cultural texts and my own fieldwork. My approach is therefore eclectic: I have brought together archival research, textual and discourse analysis and ethnography in my book. Seeing myself as a cultural studies scholar, I am less restricted by conventional academic disciplines, methodologies and approaches. This has proven to be useful. By combining texts with fieldwork, I hope that I am able to demonstrate the textual mediation of society and the ‘lived’ life of texts, which inform each other and constitute what is ‘queer culture’ in China today.

NOTCHES: Whose stories or what topics were left out of your book and why? What would you include had you been able to?

HB: Because of the people I met during my fieldwork, who were mostly young, middle-class, gay-identified men from Chinese cities, this book does have a lot of ‘blind spots’. Lesbians, transgender people, and other gender and sexual minorities are under-represented in this book (although half of Chapter 6 discusses lesbian filmmakers Shitou and Mingming’s film screening event). This omission is significant and in many ways unforgivable, especially as queer feminism has become the most radical form of queer activism in China today. Although scholars including Lucetta Kam and Elisabeth Engebretsen have both published ground-breaking work on lesbian lives and activism in China, and Leta Hong Fincher’s new book on feminist activism in China, Betraying Big Brother, is also a fascinating read, more sustained attention to queer feminist activism is certainly needed.

Another important omission results from the urban-focus of my fieldwork. Because of China’s vast geography and uneven development, queer cultures differ significantly from big cities to small cities, and from towns to villages. Although Wei Wei, Fu Xiaoxing, Zheng Tiantian, Casey Miller, James Cummings, and others have conducted significant fieldwork into queer cultures in different Chinese cities and regions, we need more grounded ethnographic research to take Chinese queer studies out of metropolises such as Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou. Recently I have also been researching and writing on some queer artists and poets from non-urban backgrounds such as queer poet Mu Cao and queer paper-cutting artist Xiyadie, in the hope to rectify the urban bias of Chinese queer studies to some extent.

NOTCHES: Did the book shift significantly from the time you first conceptualised it?

HB: Yes, when I started this project as a PhD thesis, my ambition was to write a history of homosexuality in post-Mao China. Although China has a long history of homoeroticism dating back to premodern times, and terms such as ‘same-sex love’ (tongxing ai) emerged in the Republican era as a part of the ‘translated modernity’, this history seemed to have been disrupted during the Mao era. After decades of silence, homosexuality re-emerged in the public discourse of the post-Mao era when China ‘opened up’ to the West. I was interested in the historical transition from the Mao era to the post-Mao era, and from the ‘silence’ of homosexuality to the ‘emergence’—or rather, ‘re-emergence’—of homosexuality. My questions were: under what conditions did homosexuality ‘re-emerge’ in the post-Mao era? What kinds of power relations and governing rationalities made such a shift possible? What shapes or forms does homosexuality in the post-Ma era take and how have they evolved over time? This were ambitious questions, and too big for a PhD project.

I soon realised the difficulty of undertaking such a project: the difficulty of locating and constructing an archive. There was scant literature about homosexuality in the Maoist era: supposedly ‘sexual deviants’ were all transformed into socialist subjects and good ‘comrades’. The queer history during the first two decades of the post-Mao era, from the late 1970s to the late 1990s, was equally difficult to construct. Homosexuality was considered as illegal and a disease. Only recently have queer historians started to interview older gay men and women and tried to construct a queer oral history. I am hopeful that we will be in a better position to look at China’s queer history from the Mao to post-Mao era with their new findings.

Because of the difficulty of acquiring historical data, I turned to the materials I could find, including the ‘conversion therapy’ diaries, from which I could catch a glimpse of the power and governmentality at work in making and unmaking sexual subjectivities. I also turned to queer cultural production including a popular online queer fiction Beijing Story, Zhang Yuan’s film East Palace, West Palace (often known as the first explicitly ‘gay’-themed film), and China’s leading filmmaker Cui Zi’en’s films. Textual analysis is useful but insufficient: alongside the analysis of queer representations of cultural texts, I also look at the social and cultural contexts of their production, such as the filmmakers’ life trajectory and political engagement. This has proven to be productive.

My fieldwork in China shaped this project significantly. I was not only able to experience first-hand the vitality of the queer communities and queer organising in the late 2000s, but the increasing social differentiation and stratification of China’s urban queer communities based on lines of gender, class, urban/rural divide and local and regional identities under neoliberal urbanism. More importantly, I was fortunate enough to meet some queer filmmakers who used filmmaking and film screening as a strategic way of doing queer activism. My encounter with them led the project to its media and activist dimensions.

This is a long answer to say that the project has shifted a lot: from an ambitious and almost impossible ‘history of homosexuality in contemporary China’ to a focus on queer community culture and queer activism in the first decade of the twentieth century. I see this as a positive change, as I have learned to shape my research project with the research data I get. We all have ambitious ideas informed by abstract theories, and these ideas need to be revised in light of empirical data we can acquire and social realities we live in. Also importantly, I realised that I am working in an academic community where people are working together toward a bigger project: a transnational history of sexuality if you like. Everyone has their focuses, strengths and weaknesses, and everyone plays a part in this community. It may take generations of scholars to write a ‘history of homosexuality’ in modern China, but with some persistence, perseverance and collective enterprise, we will get there eventually.

NOTCHES: How did you become interested in the history of sexuality?

HB: Foucault is the obvious influence. As a young scholar, who does not want to write a history of sexuality like Foucault did? (laugh) Western queer historians including Jeffrey Weeks and David Halperin also played a role. But these scholars are mostly based in the Global North and have a strong commitment to a ‘Western’ history of sexuality. Even Foucault had the orientalist fantasy of ars erotica in ancient China in his account of a history of sexuality in the West.

My most direct influence is from the field of Asian queer studies, and the emerging field of Sinophone queer studies. During my PhD years in Australia, I was very fortunate to meet a group of scholars working on Asian queer cultures including Peter Jackson, Mark McLelland, Fran Martin and Audrey Yue. Around them there was also a group of young queer scholars coming from different Asian countries and cultures. It was a community of scholars committed to challenging the Eurocentric ‘queer globalisation’ thesis with more contextualised, culturally specific and historically informed studies of homoeroticism in different Asian societies. It is probably a coincidence that many queer Asian studies scholars are based in Australia, but the geographical location and cultural positioning of Australia certainly inspired my own, and many others’, postcolonial approach to the study of sexuality.

Later I had the opportunity to meet queer scholars outside Australia such as Chris Berry, Howard Chiang, Travis Kong, Helen Leung, Lisa Rofel, and many others. Their scholarship has been inspirations for me too. I should also mention Li Yinhe, China’s leading sociologist who conducted the first sociological study into homosexuality in the 1990s, and Cui Zi’en, a queer writer, filmmaker, activist and a dear friend of mine. From them I have learned that academic research should serve the cause of empowering marginalised people in society, and should aim to change society. A queer community history that I am writing aims exactly to do the job.

NOTCHES: How do you see your book being most efficiently used in the classroom? What would you assign it with?

HB: The various chapters of the book were written at different times, and many were published previously as journal articles and book chapters. Each chapter revolves around a case study and has its specific theoretical concerns. I have used Chapter 2 (on queer spaces in Shanghai) and Chapter 6 (on travelling queer film festivals in Guangzhou) to teach media studies students how to conduct ethnography. A colleague used Chapter 4 (conversion therapy diaries) to illustrate the relationship between sexuality, power and governmentality. Another colleague selected Chapter 3 (‘a genealogy of queer’) and Chapter 5 (‘Cui Zi’en the queer’) to illustrate the cultural translation of queer theory. So one can start reading the book from any chapter, or select any chapter they are interested in for classroom use.

I usually assign the book chapters with some queer documentary films, including Cui Zi’en’s film Queer China, ‘Comrade’ China, Fan Popo’s film New Beijing, New Marriage, or an episode of the queer community webcast Queer Comrades. Many of these films are available online and most have English subtitles. There are many book-length scholarly references including Elisabeth Engebretsen’s Queer Women in Urban China, Lucetta Kam’s Shanghai Lalas, Travis Kong’s Chinese Male Homosexualities, Petrus Liu’s Queer Marxism in Two Chinas, Lisa Rofel’s Desiring China, Howard Chiang and Ari Larissa Heinrich’s edited volume Queer Sinophone Studies, Elisabeth Engebretsen and William Schroeder’s edited book Queer/Tongzhi China (with my contribution). It is impossible to list all of them here but please consult the bibliography of my book for further readings.

NOTCHES: Why does this history matter today?

HB: This history matters because it is always changing and fast disappearing. This is because Chinese society is changing very quickly and almost anything, as soon as it appears, immediately becomes history. This coincides with two factors: (1) government censorship of political articulations of queer culture, or activism aimed at promoting gender and sexual rights and social justice; (2) commercial incorporation of queer culture. In contemporary China, any new forms of cultural expressions can be quickly incorporated by consumerism and the market economy. The gay dating app Blued is a good example. Blued used to be a dating app serving the community; it has now been co-opted by the market to make money out of gay people, and by the Chinese government for the surveillance and control of sexual minorities. This history demonstrates the political nature of sexuality, as well as the political economy of sexual identities, desires and lifestyles.

This history is also important because it is situated at a critical historical juncture, during the transition between socialism and postsocialism. As we live in a postsocialist world, and as state-sponsored neoliberalism continues to dominate and incorporate queer culture, the socialist dimension of queer culture (and grassroots cultural production and self-organising) is all the more important. If the history of ‘queer comrades’, or tongzhi, can teach us something it is of the socialist roots and socialist aspirations of queer culture in China (and all over the world). Recognising this history is important, as it can give us strengths and inspirations to combat forms of state authoritarianism and neoliberal hegemony. I know that I sound very idealist or even utopian here, but having an ideal and being utopian is better than not having any hope, I think. Hope is what we need in this age.

NOTCHES: Your book is published. What next?

HB: At the moment I am working on two book projects, and both are extensions of the first book. My next book project is about queer community culture in contemporary China in the first two decades of the twenty-first century. I have been amazed by the energy, vitality and creativity of queer community culture in contemporary China, represented by the mushrooming of queer literature, art, theatre, film and online culture from 2000. It is true that political activism has become increasingly difficult in China today, cultural productions are nevertheless thriving, and they shape queer identities and politics in specific ways. My aim is to document some of these works that represent queer community culture before they are forgotten. The challenges of this project lie in the following two aspects: (1) criteria for selection: as we are writing about the present, or a very recent history: how do we judge if one cultural production is more important (and therefore worth documentation) than another? (2) how can an author write about things covering different disciplines and academic fields, including literature, art history, theatre and performance studies, film studies and media studies? Aware of all these challenges, I still would like to give the project a go. With the rapid changes in Chinese society and queer community culture, these works and moments are fleeting and fast forgotten. We have to document them for queer communities and for future generations, no matter how incomplete and selective this may be. I also see these cultural productions as inter-related events that occur in the same social sphere, and a mechanical adherence to disciplinary boundaries would erase the fact of their inter-connectedness. A cultural studies approach, informed by cultural materialism and a socialist politics, could help bring them together.

The second project, about queer filmmaking in contemporary China, is much more straightforward. From the early 2000s, a group of queer filmmakers have been making community documentaries and queer films. They have also been organising film screening events and community video-making workshops. They clearly identify themselves and these films with being ‘queer’ and they explicitly relate their film related activities to community building and queer activism. This is sometimes referred to as ‘new queer Chinese cinema’ or China’s ‘queer documentary movement’. After finishing my first book, I already knew that this is a topic that is worth separate treatment and it would require a book. I happen to know these wonderful filmmakers, have interviewed or worked with them, and am therefore in a good position to write the book. My ambition is to write these Chinese queer films and filmmakers into Chinese and world film histories. Whether I can achieve this goal is another question.

Now it seems that I have set myself some ambitious goals. I do not know how China’s queer history will unfold in the next few years or decades. I have decided to commit myself to documenting China’s fast-developing and fast disappearing queer community culture in the first few decades of its emergence, as this history is worth documentation and it requires a more nuanced critical understanding. I understand my work as part of the collective efforts to write queer histories and histories of sexuality transnationally. In this process, every queer researcher has a role to play and I am doing my part.

Hongwei Bao is Assistant Professor in Media Studies at the University of Nottingham. He is the author of Queer Comrades: Gay Identity and Tongzhi Activism in Postsocialist China (NIAS Press, 2018).

Hongwei Bao is Assistant Professor in Media Studies at the University of Nottingham. He is the author of Queer Comrades: Gay Identity and Tongzhi Activism in Postsocialist China (NIAS Press, 2018).

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com