December 1968. As usual, the winter was bleak in Ithaca, New York. So seemed the entire political future of the US, given the context of the Vietnam War. The last year had been a tumultuous one for radical students across North America and Europe, as they took over university spaces and city streets demanding change. The prior Spring, in May 1968, Cornell University student Jearld Moldenhauer had founded the second gay student group in the US, the Cornell University Student Homophile League, after meeting Stephen Donaldson (born Robert Martin), one of the organizers of the first student group, founded at Columbia in October 1966. Having graduated with a BSc in biological sciences in January 1969, Moldenhauer considered a move to Toronto, like so many other draft-age activists. He’d been drafted but had received a 4-F classification, meaning he had been rejected by the army on the grounds of homosexual tendencies.

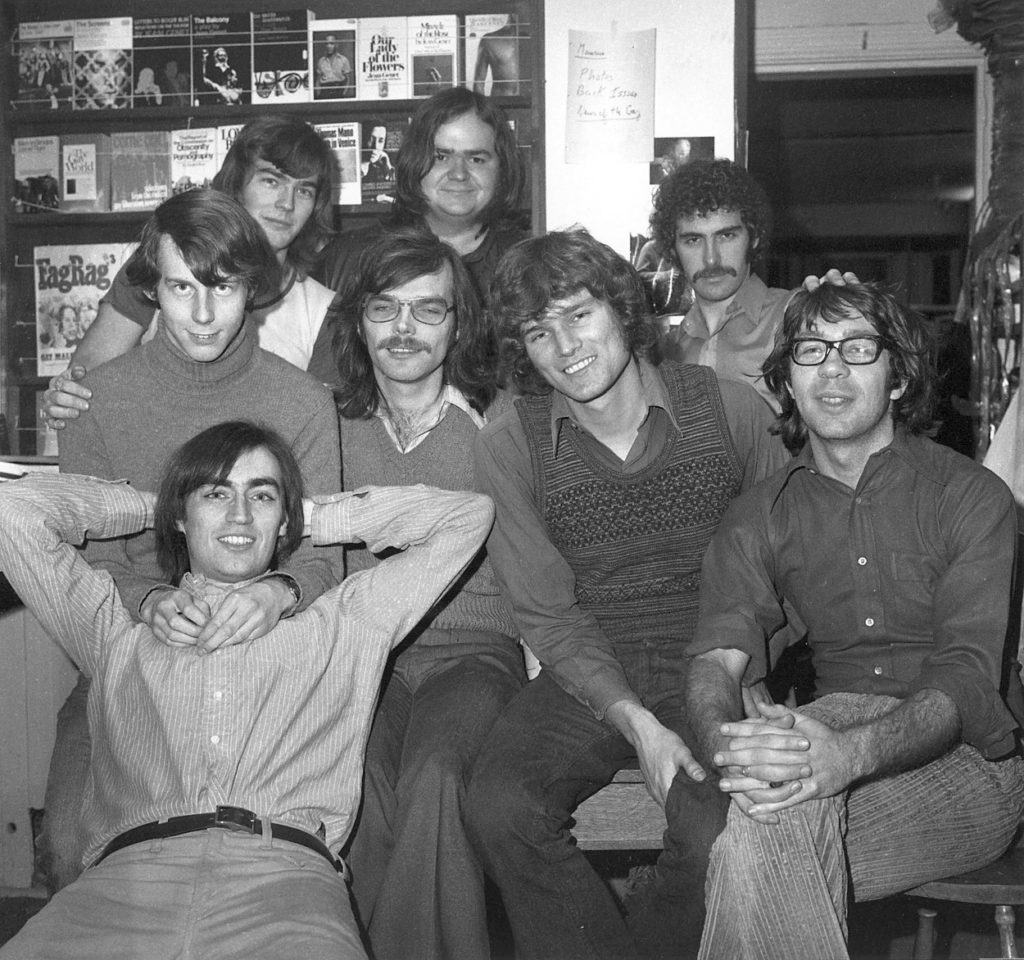

This 4-F designation eradicated most employment options in the US; in Canada, however, employers did not ask about US military classifications. He applied—and quickly got—a job in the University of Toronto’s Physiology Department as a lab researcher and, in early 1969, began a new life in Canada’s largest city. Eventually, Moldenhauer went on to become one of Canada’s most important gay activists; among other important political work, he founded The Body Politic, Canada’s gay liberation monthly, and Glad Day Bookshop, a gay and lesbian bookstore with branches in Toronto and Boston. But his first Canadian gay activism unfolded at the University of Toronto, which—unfortunately for him—also cost him his job.

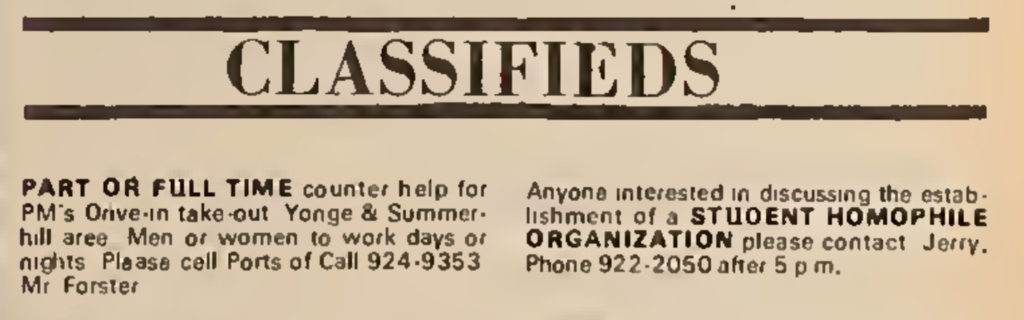

Soon after his arrival in Toronto, Moldenhauer founded his second gay student group, the University of Toronto Homophile Association (UTHA). His October 15, 1969, advertisement in the U of T student newspaper, The Varsity, was just four lines and read: “Anyone interested in discussing the establishment of a STUDENT HOMOPHILE ORGANIZATION please contact Jerry. Phone 922-2050 after 5 pm.”

Serendipitously, right after placing the ad, Moldenhauer was initiated, for the first time, in the wonders of university washroom sex. If one ever wanted to make an argument as to the centrality of sex to queer organizing, the founding of the University of Toronto Homophile Association (UTHA) would be exhibit A — because it was through having sex in the basement washroom in U of T’s University College that Moldenhauer met University of Toronto art history MA student Charlie Hill, who went on to become a key student organizer for UTHA. Readers might prefer to listen to Jearld telling this story himself, in 1986, to interviewer Lionel Collier here:

Let’s step away from the basement washroom to provide a bit of perspective on this important rendezvous. The University of Toronto Homophile Association, which emerged in the wake of this ad and intimate encounter, was the first gay student organization in Canada, and the first gay organization of any sort in Toronto. 1969 might seem late to be using the term “homophile” in an ad for a gay student group; after all, homosexuality had been decriminalized in Canada on May 14, 1969, and just one month later the Stonewall Riots erupted in NYC’s Greenwich Village. But student groups were not generally using the term “gay liberation” until the early 1970s; Cornell’s student group, for example, changed its name to the Gay Liberation Front in 1970.

For more cautious activists, the word “homophile” was less shocking than gay, which was beginning to be used at the time but was still controversial. As an activist told interviewer Lionel Collier in 1986, “We did not want to frighten too much right away, with a shock to the frosty upper Canadian Presbyterian system.” For radical activists like Moldenhauer, the term “homophile” connoted not only sexuality, but also—as he told the Globe and Mail newspaper in early 1970—a whole culture that signified “the entire complexity of feelings associated with the love of one human being for another of the same sex, not just the sexual aspects.”

From the perspective of the more radical gay liberation politics of just a few years later, the University of Toronto’s homophile organization exemplifies the homophile movement’s liberal political orientation. Their three main goals, as laid out in their 1969 constitution, included educating the “University of Toronto community and the general public about homosexuality”; assisting individuals having personal, psychological, and other difficulties due to their homosexuality; and to protest against any incidents of institutional discrimination on the basis of homosexuality. Some of the particular strategies to realize these goals included initiating public and private discussions about homosexuality; combating stereotypes; distributing literature; inviting speakers; maintaining a counseling service; letting people know of their legal and moral rights; and making referrals.

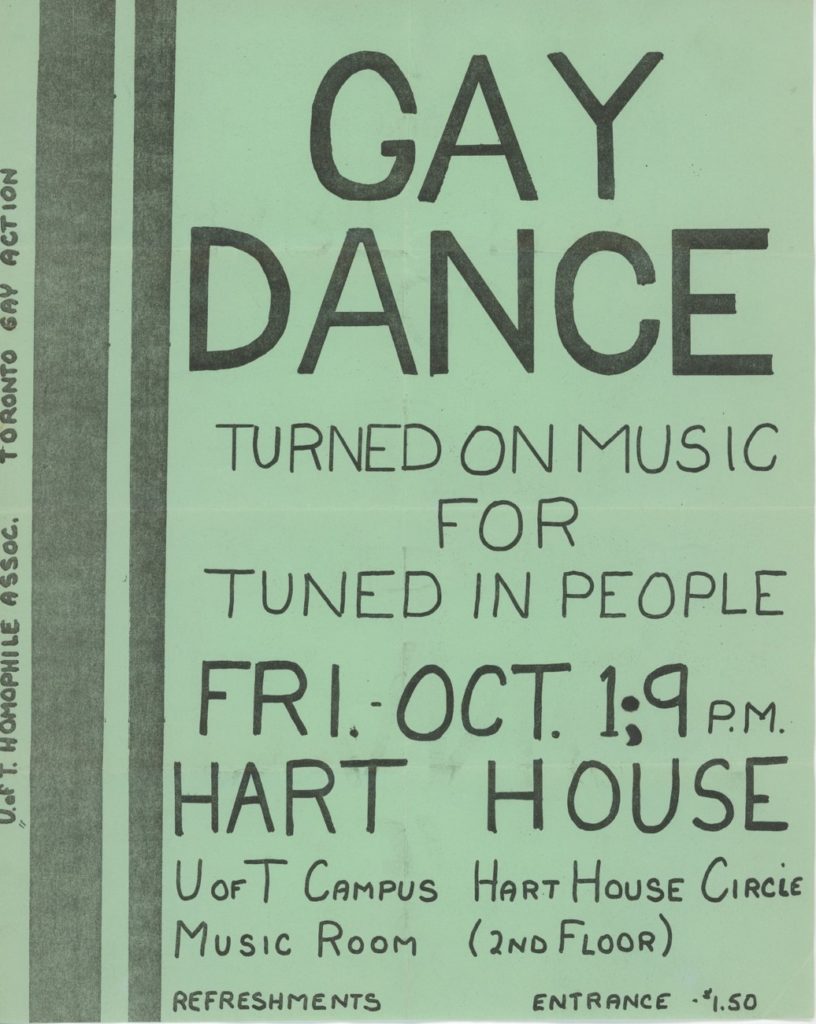

As an indication of the difference between Canada and the US at the time, the university’s Student Advisory Council (SAC) approved the new group just after its first on-campus meeting, which took place on October 24, 1969, with about 16 people in attendance. The SAC motion to recognize UTHA passed without controversy; the minutes—now located at the ArQuives: Canada’s LGBTQ+ Archive (formerly, the Canadian Lesbian and Gay Archives)—state, simply, “some discussion then followed and it was generally agreed that this was an important group especially since homosexuals were a discriminated group of citizens.” SAC’s approval meant that UTHA could qualify for student funding, reserve university space, staff literature tables at University buildings, and other activities—including holding a dance.

In the US context, in contrast, to hold something as innocuous as a gay dance was a very risky move, because to hold a dance would provide evidence to the university that the group’s purpose was to promote illegal behavior—gay sex. US universities regularly refused to recognize gay student groups through the late 1970s on the grounds that recognizing them would encourage illegal activities. In Canada, however, homosexuality had been decriminalized at a Federal level in 1969.

UTHA quickly became an important and active student organization. In addition to tabling, hosting talks, and organizing gay dances, UTHA also met bi-weekly in the graduate student union. But while things were going well for UTHA, they were not going well for Jearld Moldenhauer. His troubles with other student activists began with politics: Moldenhauer was a radical leftist whose intellectual heroes included the Marxist political philosopher Herbert Marcuse. On top of these political differences, personality conflicts and other in-group tensions led UTHA activists to refuse to vote Moldenhauer into an executive position, and within two months, Moldenhauer was effectively shut out of the organization he helped found.

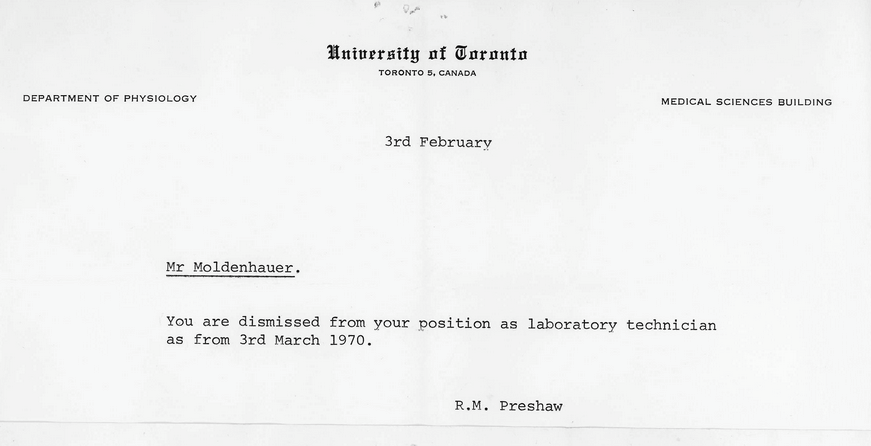

Moldenhauer’s bad luck continued on the work front. In January 1970, Moldenhauer had written a letter to the editor of Canada’s major newspaper, the Globe and Mail, rebutting a homophobic letter-writer who had written in to criticize SAC’s recognition of UTHA. In the letter, Moldenhauer came out as both UTHA’s founder and as a homophile himself. Less than one month later he was dismissed from his position by the Chair of Physiology.

In a 1986 audio clip, Moldenhauer describes how he was let go from the University in the wake of this letter’s publication. He maintains to this day that he was fired because of his activism, and I am inclined to agree with him.

The University of Toronto might have sacked Moldenhauer for being out, proud, and vocal, but they were fighting a losing battle regarding queer visibility. UTHA survived and thrived, continuing to this day as LGBTOUT. Moldenhauer went on to found Glad Day Bookshop and The Body Politic, while UTHA regulars quickly established city-wide, rather than just university-wide, activist groups. Activists founded gay student groups at York University (1970), Western University and the University of Waterloo (1971), the University of Calgary (1973), and elsewhere. Meanwhile, in 1974, English professor Michael Lynch taught the first gay studies course in Canada at the University of Toronto’s School of Continuing Studies, for which he was pushed out of his academic appointment at University of Toronto’s St. Michael’s College. But by this time, while some factions of the University of Toronto’s administration may have resisted the growing visibility of their gay students and faculty, it was clear that the lavender tide had turned.

Elspeth Brown is an Associate Professor of History at the University of Toronto, where she teaches queer and trans history; the history of US capitalism; oral history; and the history and theory of photography. She is the author of the forthcoming Work! A Queer History of Modeling and the award-winning The Corporate Eye: Photography and the Rationalization of American Commercial Culture, 1884-1929. She is the co-editor of Feeling Photography, “Queering Photography,” a special issue of Photography and Culture (2014), and Cultures of Commerce: Representation and American Business Culture, 1877-1960. Elspeth is also an active volunteer and Vice-President of the Board at the Canadian Lesbian and Gay Archives, the world’s largest LGBTQ+ community archive. She tweets @ElspethHBrown.

Elspeth Brown is an Associate Professor of History at the University of Toronto, where she teaches queer and trans history; the history of US capitalism; oral history; and the history and theory of photography. She is the author of the forthcoming Work! A Queer History of Modeling and the award-winning The Corporate Eye: Photography and the Rationalization of American Commercial Culture, 1884-1929. She is the co-editor of Feeling Photography, “Queering Photography,” a special issue of Photography and Culture (2014), and Cultures of Commerce: Representation and American Business Culture, 1877-1960. Elspeth is also an active volunteer and Vice-President of the Board at the Canadian Lesbian and Gay Archives, the world’s largest LGBTQ+ community archive. She tweets @ElspethHBrown.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com

As a young and naive new gay man in the summer of 1971 who was from the suburbs of Toronto, the dances that the UTHA put on were a godsend. What a delight to see so many “homophiles” in one room bopping away and, when the slow dances played which they did every third song or so, in each other’s arms. Bliss. Of course, we all knew Jerry Moldenhauer. He was happy to help us young men discover the joys and delights of our burgeoning sexuality. Thank you, Jerry. And Elspeth for writing this wonderful history.