Noelle Gallagher

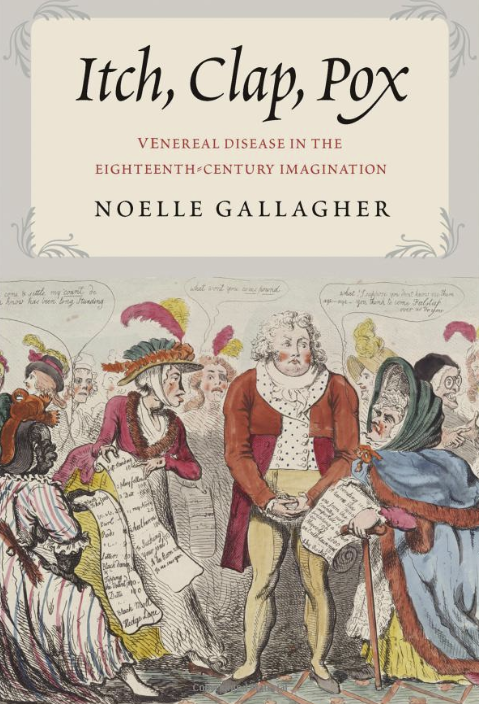

Itch, Clap, Pox: Venereal Disease in the Eighteenth-Century Imagination is a lively interdisciplinary study of how venereal disease was represented in eighteenth-century British literature and art. By unpicking the slang, symbolism and wordplay through which VD was usually represented, it sheds new light on a subject which was often shrouded in secrecy, and will fascinate anyone interested in the history of literature, art, medicine, and sexuality.

NOTCHES: In a few sentences, what is your book about?

Gallagher: Itch, Clap, Pox explores the weird and wonderful cultural life of venereal diseases like the itch (genital scabies), the clap (gonorrhoea), and the pox (syphilis) in eighteenth-century literature and graphic art. While we have a great deal of scholarship on the diagnosis, experience, and treatment of these conditions in “real life,” Itch, Clap, Pox asks what we might learn about eighteenth-century society from considering how they were depicted in novels, poems, plays, cartoons, joke books, and the like.

NOTCHES: How did you become interested in the history of sexuality, and what drew you to this particular topic?

Gallagher: I’ve always been fascinated by human sexuality, but I was starting work on another project—a book about the intersections between satire and medicine—when I began to notice all the wacky references to venereal disease in the literature of the period, and to wonder why no one had commented on the VD subtext in works like Tristram Shandy. So much of the material I was finding was outrageous, eccentric, shocking, or funny; eventually I decided to abandon the satire project and focus on the clap and the pox!

NOTCHES: Your book explores the representation of venereal disease in literary and visual sources. Why was this such an interesting topic for eighteenth-century writers and artists?

Gallagher: I think there were several reasons for the popularity of the topic. One would have been the prevalence—or perceived prevalence—of venereal disease in eighteenth-century Britain—but another would have been what scholars like Kevin Siena and Margaret Healy have identified as the potency of venereal disease as a “cultural symbol.” Satires depicting the Prince Regent’s mistress as a pox-riddled prostitute or warnings about Scottish immigrants carrying “Scotch itch and Scotch pox” into England—these images have a visceral power to shock or offend us, but they also give us unusual insight into the fears preoccupying the eighteenth-century white British establishment.

NOTCHES: How far does the portrayal of VD in art and literature reflect the reality of these conditions for eighteenth-century sufferers?

Gallagher: That’s a great question. One of the most fascinating finds for me in researching this book was realizing that there is a vast disparity between what we know about the grim realities of living with venereal disease in this period and the often comedic treatment of the condition in art and literature. While historians reading diaries, letters, and medical records have tended to conclude that the infection was universally loathed and feared, many prominent literary works from the period dismiss the disease as laughable, and some even celebrate venereal infection as a sign of virility and sexual courage. By focusing on imaginative portrayals of the disease rather than historical records of it, I’ve attempted to demonstrate that the relationship between disease discourse and disease biology is much more complicated than we might otherwise assume.

NOTCHES: Itch, Clap, Pox is a book about sex and sexuality, but it also addresses themes including gender, race and commerce. How do these topics relate to eighteenth-century ideas about VD?

Gallagher: Itch, Clap, Pox argues that venereal disease was not just a disturbing phenomenon in its own right; it also became a powerful metaphor for expressing broader anxieties about social, cultural, and economic change in eighteenth-century Britain. The four chapters of the book examine the association of venereal disease with elite masculinity, prostitution, foreignness, and physical “deformities” like the flattened nose. I argue that because venereal disease was itself regarded as ambiguous and changeable—it entered the body covertly, could lie dormant for decades at a time, and seemed capable of mimicking many other medical conditions—it offered a powerful metaphor for examining racial, social, and sexual differences that seemed equally vague and changeable in the eighteenth-century world. It provided a means by which British writers and artists could reconsider (sometimes to uphold, but at other times to question or undermine) the fundamental institutions on which eighteenth-century British society was based: patriarchy, global consumer capitalism, nationalism, and white supremacy.

NOTCHES: How did you research the book, and what particular challenges did this subject (and/ or this set of sources) pose?

Gallagher: One of the biggest difficulties—and greatest pleasures—of researching this book was in trying to puzzle through the period’s more obscure references to venereal disease. In part because the condition was poorly understood and believed to be ambiguous in nature—physicians and medical writers from the period often described it as a “shapeshifter” or “mimic”—and in part because venereal disease was still a risqué or taboo subject, many of the references to the condition in eighteenth-century fiction, poetry, and graphic art were conveyed using coded imagery, wordplay, euphemistic language, or puns. I often found myself reading texts that were clearly intended to be funny, but not understanding why: 6 glorious years of being the hanger-on who can’t get the joke.

NOTCHES: Did you find anything that particularly surprised you? And/or did you come across anything particularly interesting which you had to leave out of the book?

Gallagher: There was originally a section in the book on George Foote’s brilliant 1752 comedy Taste. Foote’s play follows a con man who tricks socially-aspiring collectors of antiquities into buying worthless pieces of junk, and its account of the sale of a “noseless Venus” picks up on many of the motifs and images that run through eighteenth-century satires about noseless venereal disease sufferers. (One of the rarer symptoms of tertiary syphilis is the collapse of the nasal cartilage, making the sufferer appear flat-faced or “noseless”). Yet while Taste makes great comic work of the Venus and displays the same social conservatism, anti-semitism, and racism that run through many other “no-nose” jokes from this period, it doesn’t ever explicitly refer to venereal disease—a difficulty pointed out to me by my friend and colleague Hal Gladfelder when he read the text in draft. Identifying all those coded references to venereal disease was a challenge and a pleasure, but it also meant that I occasionally “followed my own nose” a little too earnestly, and ended up veering too far away from the topic of the book! I was lucky to have readers like Hal to keep me on track.

NOTCHES: How do you see your book being most effectively used in the classroom?

Gallagher: Itch, Clap, Pox brings together medical, historical, literary, and artistic materials—but I wanted it to be accessible to scholars at every level, from first-year undergraduates to established professionals. I know it has been assigned on a couple of postgraduate medical humanities courses, but I also hope it will be of use for students of eighteenth-century literature, art history, the history of medicine, and/or the history of gender and sexuality. Since each of the book’s four chapters focuses on a different concept, I expect different students will be interested in different chapters: students of gender and sexuality might read the first two chapters (which are about masculinity and prostitution, respectively), whereas students interested in the history of medicine, scientific racism, or the history of eugenics might focus on the final chapter about nasal “deformities.” There are also prolonged sections on individual works, so art historians might use the material on Hogarth, Gillray, or Cruikshank, while literary critics might use the extended discussions of Rochester’s poetry, or novels by Sterne, Smollett, Fielding, and the like. In short, I’m hopeful the book will have something for (almost) everyone.

NOTCHES: What are you working on now that this book is published?

Gallagher: I’ve just started working on a project about bodily secretions. Itch, Clap, Pox may be followed by “snot, sweat, and tears”; we’ll see how it goes!

Noelle Gallagher is Senior Lecturer in Eighteenth-Century Literature and Culture at the University of Manchester. She is the author of Historical Literatures: Writing About the Past in England, 1600-1740 (Manchester University Press, 2012) and Itch, Clap, Pox: Venereal Disease in the Eighteenth-Century Imagination (Yale University Press, 2018).

Noelle Gallagher is Senior Lecturer in Eighteenth-Century Literature and Culture at the University of Manchester. She is the author of Historical Literatures: Writing About the Past in England, 1600-1740 (Manchester University Press, 2012) and Itch, Clap, Pox: Venereal Disease in the Eighteenth-Century Imagination (Yale University Press, 2018).

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com