Bob Cant

In 2009, I addressed the LGBT Trades Union Congress (TUC) about the Millthorpe Project, a sound archive of the lifestories of LGBT trade unionists. Thirty years previously, it would have been inconceivable for the TUC to host an annual event about issues facing LGBT people at work.

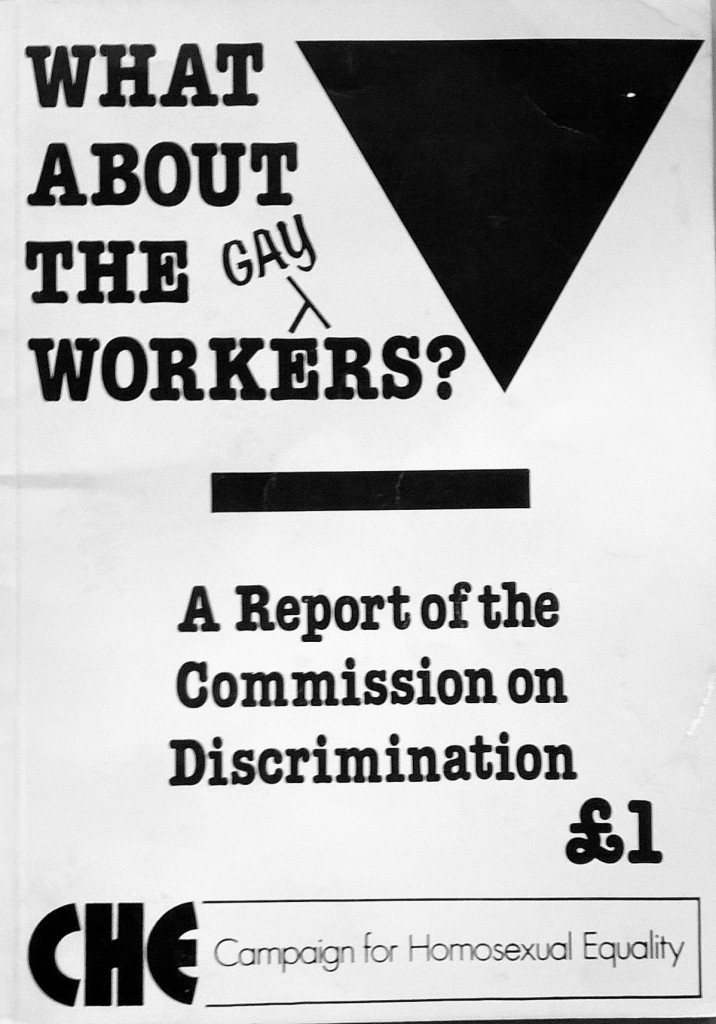

I recall a publication entitled, ‘What About The Gay Workers?’, which was produced by the Campaign for Homosexual Equality (CHE) in 1981. CHE was not the only organisation to be engaging with the question of being gay – or openly gay – in the workplace but it was the only one to conduct a national survey of all sixty-three unions affiliated to the TUC. There were an increasing number of critiques of trade unionism from people, including contributors to the Gay Left and Red Rag journals, who recognised the importance of organisations to defend working people but argued that unions had become a movement which primarily reflected the concerns of married male breadwinners. Homosexual people were marginalised by such a heterosexist hegemonic approach. That was not the language of CHE but their survey of trade unions revealed a great deal about the values that underpinned much trade union practice.

Tom Robinson, in his song, Glad To Be Gay, had captured a widely held view when he asked the question: ‘The buggers are legal now, what more are they after?’ It reflected the bewilderment of some sections of society about the fact that the Sexual Offences Act (1967), rather than marking the end of the story, opened up the potential for the development of something new and transformative. The responses from the trade union survey (including the silence of twenty nine unions) suggested Robinson’s words were highly appropriate as an indicator of the mindset of much of the trade union movement.

The response of the General Secretary of the Bakers’ Union was widely reported on account of its sheer viciousness. “What do you want equality with – pigs or dogs?” (‘What about the Gay Workers?’, p. 17). Far more representative of those unions that did reply was the Confederation of Health Service Employees (COHSE): “We represent those who are homosexual, whether lesbians or gay men, from the point of view of having the service of the union as any other members. In fact, we do not have heterosexuals or homosexuals in membership – we have members.” (‘What About the Gay Workers?’, p. 21). The principle of unity lies at the heart of trade unionism and any distinction between members was seen as being divisive, rather than a clarification of the experiences that particular workers might have on account of the stigmatisation of their sexuality. Diversity was neither appreciated nor welcomed.

The CHE survey proved to be like an anthropological photograph, capturing a population at a moment before they were transformed into something different. Some of the transformation of trade unions resulted from anti-union legislation and economic changes but some of it was to result from changes within the movement instigated by LGBT people themselves.

Further Reading: ‘What About the Gay Workers?: A Report on the Commission on Discrimination’, ISBN: 0 9504429

Bob Cant has been a teacher, a trade unionist, a community development worker, a Haringey activist and an editor of several collections of LGBT oral history. He now lives in Brighton and his first novel, Something Chronic, was published in October 2013. Bob tweets from @bobchronic

Bob Cant has been a teacher, a trade unionist, a community development worker, a Haringey activist and an editor of several collections of LGBT oral history. He now lives in Brighton and his first novel, Something Chronic, was published in October 2013. Bob tweets from @bobchronic

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com