Interview by David K. Johnson

Historians who study sexuality in the 20th century United States have largely worked from the premise that secular forces shaped the formation of sexual identities, communities and regulation. Religion, in this paradigm, is framed as a residual and conservative force—the province of the fanatical and the ignorant. Historians who have adopted this paradigm have ignored or misunderstood the critical and diverse role of religious ideas, practices and institutions to the modern history of sexuality in general and LGBTQ history in particular. Heather R. White‘s Reforming Sodom: Protestants and the Rise of Gay Rights breaks new ground by revising our assumptions about LGBT history and its complex relationship to American religions.

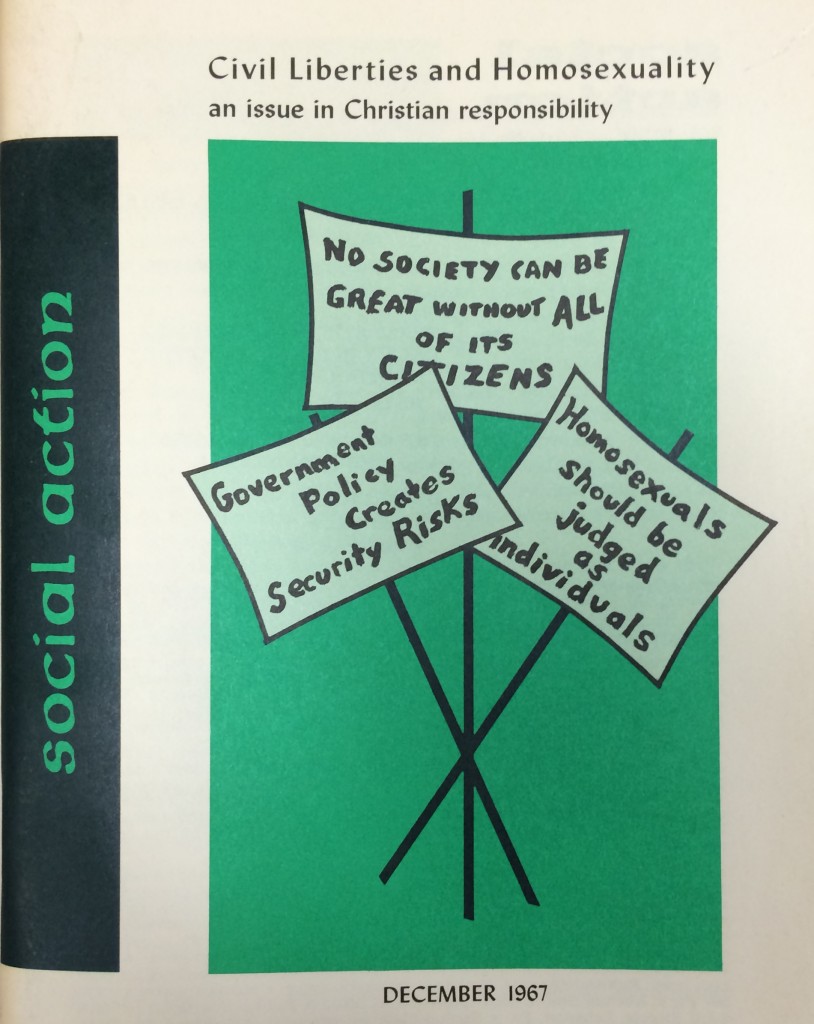

With a focus on mainline Protestants and gay rights activists in the twentieth century, White argues that today’s antigay Christian traditions originated in the 1920s when a group of liberal Protestants began to incorporate psychiatry and psychotherapy into Christian teaching. A new therapeutic orthodoxy, influenced by modern medicine, celebrated heterosexuality as God-given and advocated a compassionate “cure” for homosexuality. White traces how the therapeutic model shifted in the post-World War II period and led mainline church leaders to challenge rampant antigay discrimination. By the 1960s, a vanguard of clergy advocated for homosexual rights even as continued religious support was essential to an emergent gay and lesbian movement. Because it challenges the assumed secularization narrative at the center of LGBT history by recovering the forgotten history of liberal Protestants’ role on both sides of the debates over orthodoxy and sexual identity, Reforming Sodom is essential reading for historians of sexuality.

David K. Johnson: You begin Reforming Sodom with the 1946 publication of the New Testament of the Revised Standard Version (RSV) of the Bible, which you identify as the first time the word “homosexual” appeared in an English-language Bible. It is a powerful reminder that what is often taken as Christianity’s “clear” condemnation of homosexuality is strikingly new, and not really that clear. Much of your book is a refutation of this myth that Christianity has always been hostile to gay rights. Why is this myth so persistent?

Heather R. White: I should first explain briefly why I highlight the RSV, which was a Bible translation completed by liberal Protestants and hailed as the “the first modern Bible.” Most American Christians today read a version of the Bible that has in some way been shaped by the RSV—even through translators of many of the later versions criticized the RSV as a “liberal” Bible. The RSV especially influenced the wording of the Bible verses that appear in today’s debates about the Bible and homosexuality. The “homosexual” meaning of these passages was not at all clear for the earlier readers of the seventeenth century translated King James Bible. In fact, the King James includes a whole set of passages about “sodomites” that are not addressed for meaning about homosexuality today. I could (and do) say much more about the history of the interpretation of these passages, but the key takeaway is this: modern Bible-readers think that the Bible clearly condemns homosexuality because the wording of modern bibles was influenced by new medical paradigms for sexuality. That wording reflects the influence of Sigmund Freud rather than the outlook of the Apostle Paul.

I offer this background on Bible translations because I think it’s a big part of why so many people see Christianity as a historical source of modern homophobia. Lots of people—whether they read the Bible for spiritual truth or view it as an historical artifact—imagine “the Bible” as a singular book with readily accessible meanings that clearly condemn homosexuality. And they assume from there that Christianity—and often religion in general—has always been hostile to gay rights.

But those anti-homosexual Bible meanings are also widely known today because they’ve been repeatedly trumpeted by anti-LGBT politicos. So, another reason for the pervasiveness of today’s view of Christian homophobia has to do with the political and cultural influence of the Christian Right. In the late 1970s, this set of organizations influentially mobilized a “family values” agenda that also worked to cement into place a popular view of Christianity as normatively conservative and historically homophobic. These conservatives thoroughly eclipsed the earlier influence of their liberal co-religionists, and they castigated liberals for having an essentially non-religious or secular point of view. Many of those liberals, by the 1970s, had begun to challenge the earlier antihomosexual interpretations of the Bible. But the irony is this: people like Jerry Falwell were subtly influenced by those supposedly secular liberals. Conservative cultural warriors plucked up liberals’ Freudian-inflected Bible interpretations and recast them as an anti-gay tradition.

DKJ: You rightly take scholars of gay and lesbian history to task for our reluctance, even aversion, to talking about religion, except as an oppressive force. I confess to being one of those historians who has been faulted for ignoring religion. I remember in my own research on the homophile movement of the 1960s being surprised to see that early Mattachine group meetings were often held in Protestant churches. Frankly, I didn’t know what to make of it, since it countered our standard understanding of church hostility to gay rights. How do you explain the absence of religion in LGBT history and how do we move beyond it?

HRW: This anecdote is perfect: of course the Mattachine society met in churches, and of course you were confused! One of the great delights of this project was to connect those seemingly inexplicable local examples to show a broad pattern. Leaders of homophile organizations deliberately cultivated ally relationships with local clergy, and many—if not most—of those homophile organizations got started and stayed afloat with the support of sympathetic churches and clergy. But your perplexity is also part of a broader pattern as well. There are dozens of locally-focused LGBT histories that tell of similar discoveries with the assumption that the sympathetic clergy in their city must have been oddball outliers. So, over and over again, historians working on LGBT history have found it difficult to gain any kind of analytic perspective on these instances of religious support.

The reasons for this difficulty, I’d say, share in the larger cultural perception of religion as normatively conservative and historically homophobic. And LGBT scholars have not been the only ones with this problem—Jon Butler’s 2004 essay, “Jack-in-the-Box Faith: the Religion Problem in Modern American History” suggests that the field of twentieth century American history has suffered from a similar inattention to religion, which tends to be recognized and analyzed as a resurgent conservative force rather than an ongoing influence. An additional dynamic for LGBT history is also that most of the foundational literature in the field was written after the religious politics shifted with the post-1980 consolidation of the Christian Right. The terms of the public political debates certainly reinforced that “standard understanding of church hostility.”

DKJ: You provide new insight into the famous 1965 police raid of the New Year’s Eve Ball at California Hall in San Francisco. This event was organized by the city’s six homophile organizations and supported by local clergy members, who had formed The Council on Religion and the Homosexual (CRH). Most historians who have discussed the New Year’s Eve Ball compare it to Stonewall, since it was a police raid on a gay space. But you suggest this is the wrong comparison. How might we better contextualize this important early example of gay resistance? How does spotlighting the role of religion in this seminal gay rights moment transform our understanding of the history of LGBT social movements?

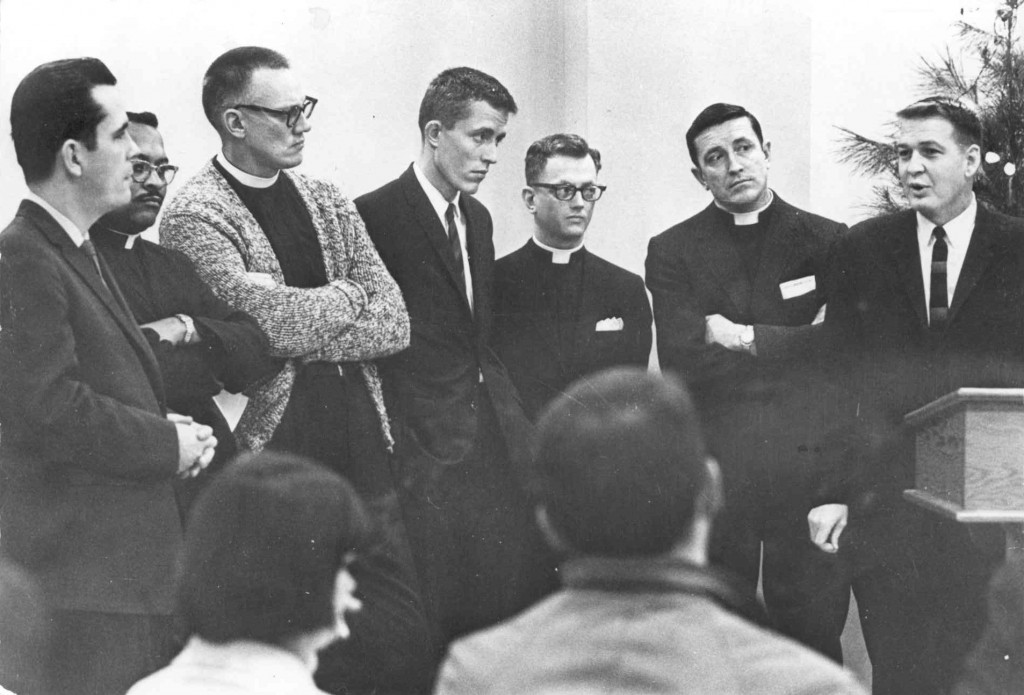

HRW: What I argue in that chapter is that homophile activists in San Francisco were comparing their struggle for homosexual rights to two other movements in which clergy played a key role in the visual politics of moral resistance. Those two movements were the British movement for homosexual law reform, in which Anglican clergy played a publicly supportive role, and the movement for African American civil rights, which prominently featured Reverend King as well as influential Jewish and Catholic religious leaders. Homophile leaders in San Francisco founded the CRH to harness moral authority that had been so important to these contemporaneous struggles for justice.

Quite a number of historians have discussed the formation of the CRH, but they missed the national networks that formed as a result of this organization. One reason for that inattention, as mentioned above, was the perception that the San Francisco clergy represented a local anomaly. But the other issue was that the comparison to the rapid movement growth attributed to Stonewall made the extent of the CRH’s national influence seems inconsequential. I became really curious about why these clergy were joining in the homophile movement. I found that there were various institutionally supported projects within liberal-leaning wings of Mainline Protestant churches, which trained ministers for urban ministry, social justice, and young adult programming. Those networks also helped to enable clergy alliances with homophile groups. And then those urban social justice ministries provided support for building the national networks in the homophile movement.

DKJ: Like many historians of the gay rights movement, you are engaged in the process of debunking the popular narrative that places Stonewall at the origin of the movement. But rather than simply making the obvious historical point that organized LGBT activism already had a twenty-year history by 1969, you analyze this origin story through the lens of religion. You observe that the way we commemorate the Stonewall riots each year in pride celebrations is “strikingly religion-like.” You draw fascinating parallels between these pride commemorations and Christian narratives and practices, suggesting that these commemorations offered “a perfect vehicle for fusing gay and religious identities into a seamless whole.” (141) Tell us how this fusion works and what it means for our broader understanding of gay identity and politics after Stonewall.

HRW: As I worked on this history, it was impossible for me to miss the ritual and religious imagery found in the popular histories of Stonewall and the commemorative practice of Gay Pride Parades. Every year—to this day—LGBTQ people in New York and in hundreds of other cities gather for an annual day of commemoration, which remembers a Friday night act of violence with a celebratory Sunday march for “Gay Pride.” (The riots at the Stonewall Inn actually began early Saturday morning) This commemorative practice began the year after the riots at the Stonewall Inn, when activists planned an anniversary demonstration to celebrate the one-year “birthday” of gay liberation. They planned the route of the march to reenact a symbolic journey from shame to pride—activists met outside the shuttered Stonewall Inn (seen at the time as a symbol of oppression) and marched to Central Park for an outdoor “Be-In.”

I’m not the first historian to highlight the importance of the pride commemorations to the making of the so-called “Stonewall Myth,” which mistakenly credits the Stonewall riots as the beginning of the modern movement for gay rights. But instead of adjudicating the truth claims of the myth, I show how the symbolic meanings that gave undue credit to Stonewall also communicated ideological meanings for shaping a new self. Even more important, those ideological meanings also echoed Christian religious narratives about suffering and rebirth.

This reframing of the Stonewall narrative also helps to foreground a part of 1970s gay history that often remains at the sidelines, and that is the rapid growth of gay-welcoming religious groups. By 1978, for example, the Metropolitan Community Church was the largest national grassroots gay organization in the United States. Gay-welcoming Catholic, Jewish, Mainline Protestant, and even Evangelical and Mormon groups also began during these years—which counters the dominant picture of the 1970s as a radically secular moment of activism. The Stonewall narrative, as I show in that chapter, provided an important resource in which the formation of an “out and proud” identity was also a spiritual project.

DKJ: One of the rhetorical tropes you often use is one of visibility—you suggest that your goal is to “make visible” ideas and concepts that have been hidden from us for decades, particularly the interconnections between religion and the gay rights movement. One of the ways you make these connections visible is by showing how some Protestant churches were at the forefront of efforts for tolerance and inclusion. If we move away from an oil and water model that understands organized religion as repulsing gay rights, how then should we conceptualize the historical relationship between Protestants and gay rights in the United States?

HRW: I am arguing that in many ways “gay rights” as we know it took shape as a Protestant political project. It’s easy to identify the religiosity of anti-LGBT efforts, but my book argues that the opposite is just as true: religion, and especially Protestantism, has profoundly shaped pro-LGBT movements and politics. We don’t see that influence because of the way our analytic register for “religion” has focused primarily on instances of conservative opposition. However, when we broaden the register for religion to give analytic attention to those churches and clergy that have played roles of support, we also begin to see the distinct ways that they have influenced the rhetoric and ideals of pro-LGBT movement building.

I would also add—my aim for making this influence visible is not to vindicate religion in general or liberal Protestantism in particular. Rather, I wish to encourage further attention to the ways that the seeming secularism of LGBT rights has been shaped by a Protestant paradigm.

David K. Johnson is an Associate Professor of History at the University of South Florida. He specializes in American political and cultural history since World War II with a particular interest in issues of gender, sexuality, and the LGBT community. His first book, The Lavender Scare: The Cold War Persecution of Gays and Lesbians in the Federal Government, (University of Chicago, 2004) has become the basis for a documentary film currently in production by Emmy-award winning director Josh Howard. He also co-edited The U.S. Since 1945: A Documentary Reader (Wiley-Blackwell, 2009), an anthology of primary source documents for students studying modern American politics and culture. Johnson is currently completing the book “Buying Gay: Physique Magazines, Censorship, and the Rise of the Gay Movement,” which chronicles the rise of a gay commercial network in the 1950s and 1960s.

Heather White is Visiting Assistant Professor in Religion and Queer studies at University of Puget Sound. Her first book, Reforming Sodom: Protestants and the Rise of Gay Rights was published by the University of North Carolina Press in 2015. The book has been featured in Huffington Post, Religion and Politics, the L.A. Review of Books, and Religion Dispatches, and it was listed in the top ten “best LGBT nonfiction of 2015” by the Bay Area Reporter. She is also co-editing an anthology (with Gillian Frank and Bethany Moreton), titled Devotions and Desires: Histories of Sexuality and Religion in the Twentieth Century United States.

Heather White is Visiting Assistant Professor in Religion and Queer studies at University of Puget Sound. Her first book, Reforming Sodom: Protestants and the Rise of Gay Rights was published by the University of North Carolina Press in 2015. The book has been featured in Huffington Post, Religion and Politics, the L.A. Review of Books, and Religion Dispatches, and it was listed in the top ten “best LGBT nonfiction of 2015” by the Bay Area Reporter. She is also co-editing an anthology (with Gillian Frank and Bethany Moreton), titled Devotions and Desires: Histories of Sexuality and Religion in the Twentieth Century United States.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com

One Comment