Editor’s Note:

Last week, as social media websites flooded with criticism of far right agitator Milo Yiannopoulos for comments he had made in defense of sexual relationships between male youths and adult men, the novelist and essayist Sarah Schulman posted a public comment to Facebook reminding followers that such erotic relationships were once common and accepted within the queer community. Her post provoked over one hundred comments from followers. Some were thankful comments from queer folk who had positive memories of intergenerational relationships they had entered into as youths. Others were angry comments from individuals, queer and straight, who as children had been sexually exploited by adults, or who just vociferously disagreed with what they saw as a defense of child abuse.

As a historian of sexuality, I felt gratitude to Schulman for opening this difficult conversation. The history of sexuality teaches that the meanings of sexual acts, identities, and relationships are shifting. We know that in many times and places, intergenerational sex—especially between male youths and men—was widely practiced.

Today, the consensus within North America and Western Europe clearly identifies such sex as intolerable. But the history of sexuality also teaches us to think critically about “sex panics,” in which certain groups are deemed monstrous and exploited for political ends. Thus, in the interests of promoting critical discussion about the complexity of sexuality in the past and present, the Editors at NOTCHES invited Schulman to expand her Facebook comment, and her ideas about the historical explanations for how attitudes towards intergenerational sex have changed in recent decades.

On February 19, 2016, a white nationalist gay man was propelled to the heights of media glamour, inspiring my following Facebook reflection:

I want to weigh in on the Milo phenomenon. It is a long standing practice for corporate media and straight people to elevate right wing gay men and inflate their visibility and personal power. You don’t have to look back very far to uncover the crowning of then Republican Andrew Sullivan (of “AIDS is Over” infamy) giving him more air time than anyone actually rooted in the queer community. They found this Milo creep to motivate their campaigns against vulnerable people: Trans people, Muslims, Black women, and immigrants. But do not be fooled: this is an old trick powered by corporate interest. Without them he is nothing.

A few days later he was brought plummeting down because of a comment about intergenerational gay male sex. I posted (a shorter version of)R this follow-up:

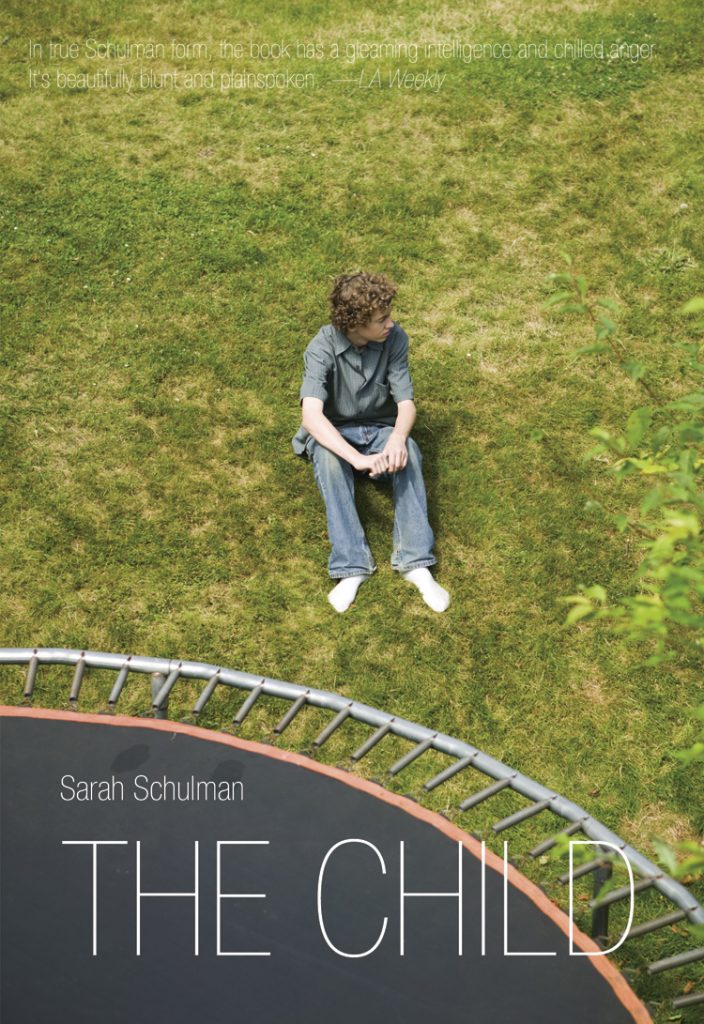

In 1999, I wrote a novel called The Child about a sexual and romantic relationship between two men: a 15 year old and 40 year old. It was influenced by a case in New Jersey where a young man, Sam Manzie, went online looking for an older lover. When his boyfriend was later arrested by an FBI internet sting, Sam was exposed to his homophobic family and humiliated by his parents and the state. He had a psychotic break and murdered a little boy. Ironically, and tragically, the state then tried him as an adult, while still insisting that in relation to his lover, he was a child. This question of being considered too young for pleasure but old enough for punishment intrigued me.

Up until that time, when I was growing up, it was normal for gay men in my world to openly include their teenage sex with older guys as a reported regular and positive part of coming out histories. There was no stigma around discussing these experiences, even if the relationships were socially transgressive—and they figured prominently in the works of writers like Edmund White’s The Beautiful Room Is Empty and John Preston’s stories about his teenage years.

But a few paradigm shifts occurred at the end of the twentieth century. The facts of intergenerational sex were not concealed, indeed—in the West—gay men looked for centuries to the Greeks for affirmation of love between generations, and the worship of youthful male beauty. The aesthetic transformation that came with Oscar Wilde and the addition of camp to classics, was made more visible by his ruinous relationship with a younger man, Lord Alfred Douglas. Gay Liberation, of course, emerged as a sex and love movement, looking to expand possibilities for all people in the realms of desire, exploration, love, gender, and relationships. The age of consent was a central subject in the discourses of that era—with groups like Gay Youth and North American Man/Boy Love Association (NAMBLA) having organizational ties around the subject (see my interview with Aner Candelario in The ACT UP Oral History Project). As the community institutionalized, NAMBLA—an organization that needs to be rehistoricized—was the first gay organization to be excluded, in a sea of contention, from the LGBT Center in New York City, a distinction shared only with the New Alliance Party and Palestine Solidarity Activists (the latter was reinstated after thousands of people protested over two years). But the casual acknowledgement of teenage male sex with adult men, as a common part of gay experience became—I would say—abruptly halted, in my anecdotal view, by three events.

1. Starting in the late 1980s, the Catholic Church became embroiled in scandal. Again, this is an event that needs real work by a real historian to be understood in a queer context, but long-term sexual abuse by priests began to be widely exposed. It became clear that the sexual restrictions and social dysfunctions of the clergy had created a culture in which sexual abuse was significant. More importantly, the hierarchy of the Church was revealed to be condoners and enablers of abuse, by covering up accusations and putting accused priests on placement rotations. However, I believe, that real exploitation by priests became conflated with the simultaneous reality of gay sexual expression in the oppressive world of Catholicism. The gay desire of young men, living in oppressive homophobic and yet male supremacist and homosocial Catholic Church culture, had means of expression in the Church’s gay subculture. And as some of these relationships also came to light, they became conflated with abuse. I think that the evidence for this conflation is that the public conversation of priest abuse did not also include an emerging category of recognized gay male desire and sexuality within the Church. All male sexuality in Church context became framed as “abuse” in the popular discourse.

2. By the 1990s, home computers were becoming normal parts of bourgeois and even some working-class lives. Certainly employment had transformed homes into workplaces, which disrupted intimacy. And intimacy itself shifted as contacts, information, and relationships became available in new ways. Real friends could be blocked, while strangers could be pursued. Internet dating made sexual contact with the “stranger” increasingly possible. Internet porn availability allowed anyone to see any act or naked body about which they had curiosity or attraction. Both the sexual realities and imaginaries inflated. And as computers interrupted family relationships and became avoidance instruments, the relationships of children to computers became an arena of confusion. In this environment, anxiety about the integration of computers, as pleasure objects, into daily life fueled public panics about “internet predators” and other outside adult dangers to children. The possibility of online predators became a national obsession, with television shows devoted to entrapping men. Of course this fixation on unknown, outside adults being dangerous to children via machines obscured the ever-present danger that children face within their own families.

3. As the AIDS crisis forced mass gay visibility, especially through the formerly restricted mass media, gay respectability politics in the drive towards same-sex marriage prioritized images of gay relationships and sexuality based on the predominant heterosexual model. At that millennial nexus, these stories about desirable and positive intergenerational gay male sex disappeared from the public discourse. Gay marriage emphasized the white appropriate couple, with an illusion of monogamy and implied HIV negativity, as the poster models. This was part of the erasure of the concept of queer sexual culture as something different from heterosexual expectations and norms.

And PS: it took me ten years to get that damn novel published, but I did, and it is still in print.

The events of this week show us yet again that someone receiving approval and reward when we mimic myths about heterosexual life including ideology about white, cis gender, and Christian supremacy, can get taken down for displaying difference or resistance to those tropes in a way that exposes repressed sexual histories.

Sarah Schulman is a Distinguished Professor of the Humanities at College of Staten Island and a Fellow of the New York Institute for the Humanities. Her most recent books are Conflict is Not Abuse, a plea for people to negotiate on all levels of social interaction, and The Cosmopolitans, a novel set in Greenwich Village in 1958. She tweets from @sarahschulman3

is a Distinguished Professor of the Humanities at College of Staten Island and a Fellow of the New York Institute for the Humanities. Her most recent books are Conflict is Not Abuse, a plea for people to negotiate on all levels of social interaction, and The Cosmopolitans, a novel set in Greenwich Village in 1958. She tweets from @sarahschulman3

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com