In 1965, a Jewish couple living in Venezuela contacted the Jewish Child Welfare Bureau (JCWB) of Montreal and asked about the possibility of adopting a Jewish child. The JCWB declined their request and told them that due to the small number of Jewish children eligible for adoption, they only placed children with permanent residents of the city. They tried to entice the Venezuelan couple to adopt children that were harder to place: mixed-race children born to white Jewish mothers and Black Canadian fathers.

Montreal’s Jewish Child Welfare Bureau reflected the widely held view in Jewish communities that reproductive intra-faith sex was vital to shoring up racial-religious boundaries and to reproducing Jewish religion and ethnicity. Indeed, Jewish institutions such as the JCWB regulated reproduction and reproductive outcomes, including adoption, in order to construct and preserve Jewish identity in interracial and interethnic contexts.

For the gatekeepers of the Jewish community of Montreal in the postwar period, their understanding of Jewishness only extended as far as their racial prejudices. Jewish religious law specifies that religion descends through the maternal line. Therefore, any child born to a Jewish woman is automatically considered Jewish. When faced with the children of Ashkenazi Jewish mothers and Black Canadian fathers, the JCWB redrew the boundaries of Judaism along racial lines.

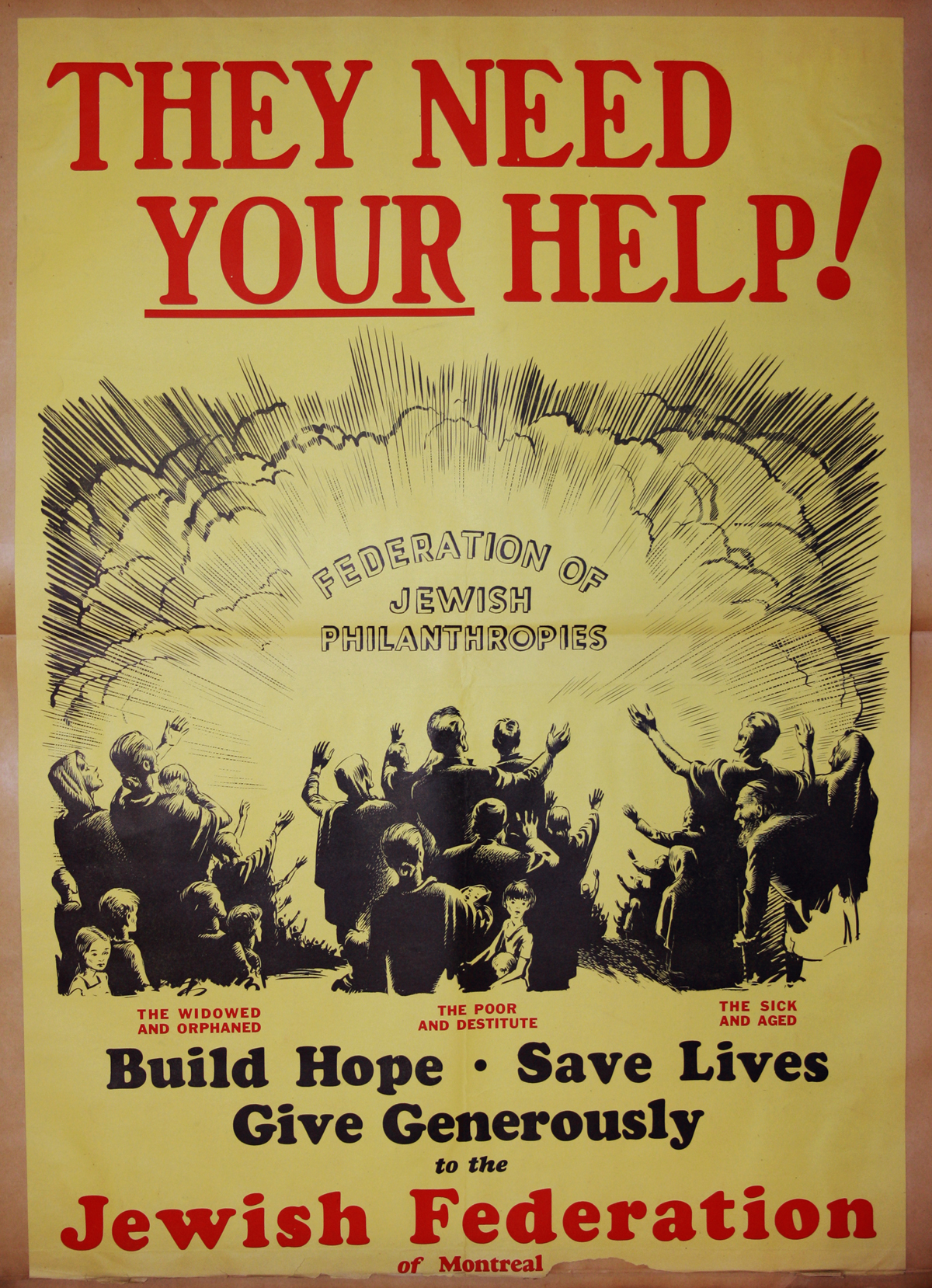

The two solitudes—the ongoing disconnect between Anglophones and Francophones—shaped legal adoption in Quebec, which began with the 1924 Quebec Adoption Act. Within a year, the Catholic Church used its tremendous political influence to have the law modified so that non-Catholic families could not adopt Catholic children. The amended law stipulated that adoption would be restricted by religion and that a child’s religion would be determined by the religion of the child’s mother. Religious institutions, in turn, became responsible for regulating adoption within their own communities. The JCWB—a division of the Baron de Hirsh Institute, the largest Jewish philanthropic organization in the city—thus came to oversee the adoption of Jewish children in Montreal.

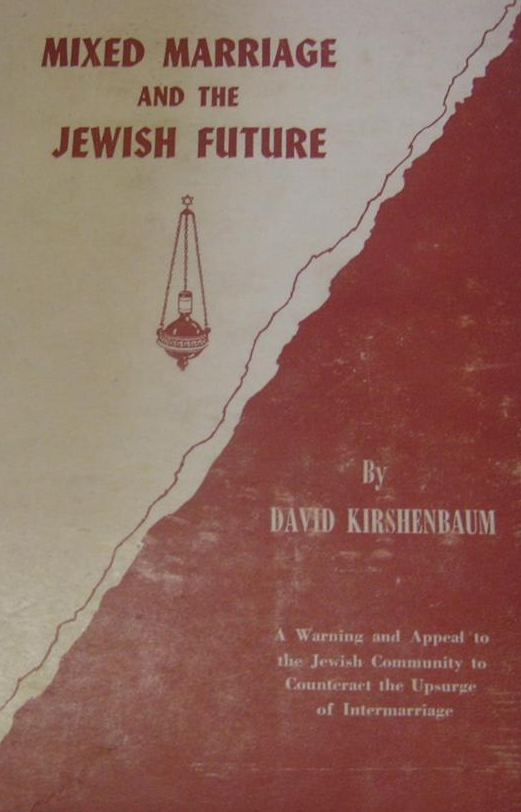

In the postwar period, most of the Jewish children available for adoption came from unmarried Jewish mothers. A number of these women had interfaith relationships. Montreal’s tightly knit Jewish community frowned on interfaith relationships and interfaith marriages led to ostracization. The stigma was such that the intermarriage rate for Montreal’s Jewish women in the 1960s was less than 5%. I interviewed 35 Jewish women about their experiences growing up in Montreal during the 1950s and 1960s. Five of these women admitted to having dated non-Jewish men. Each narrator explained that these relationships were temporary, since non-Jewish men were not considered to be acceptable spouses. Narrators related that their parents would “sit shiva” for them if they were caught dating non-Jewish men, which was (and is) the Jewish parent’s way of saying “you’re dead to me.” One woman even described how her father warned that if he ever caught her dating a non-Jewish boy, he’d “break every bone in his body.” Jewish women were also explicitly forbidden from dating Black men. For instance, one of my interviewees, Leah, came home to see her daughter entertaining a Black man. After he left, she turned to her daughter and asserted: “You’re not going out with a schvartze!”

The pressure on Jewish women to avoid interfaith and interracial relationships was so great that when faced with an accidental pregnancy with a non-Jewish man, many chose to surrender their children for adoption. The case of Ms. F, who approached the JCWB in March of 1958, was fairly typical. She was, at the time, six months pregnant. When asked about the child’s father, Ms. F specified that although she was very fond of him, “she could not marry him as she comes from an orthodox background and apart from her family’s feelings about it, she has strong feelings of Jewishness and could not marry a Gentile.”

The existence of Jewish children born to non-Jewish and non-white fathers presented a serious threat to the imagined Jewishness of the community. These babies were visual evidence of racial transgressions, proof-positive that at least some Jewish women were having sexual relationships with Black men.

As the number of unwed mothers who gave up children for adoption grew in the 1950s and 1960s, the JCWB’s Board of Directors and Adoption Committee rigorously screened prospective adoptive children to determine their Judaism and their overall fitness. Some children were not considered adoptable because they demonstrated existing or potential mental and physical disabilities. Included in the same “unadoptable” category were children from “mixed racial” backgrounds. Children who were deemed “unadoptable” were usually sent to institutional care. Where “problems such as mixed racial factors exist[ed]” the JCWB was willing to “place children for adoption outside our jurisdiction.”

Unfortunately, most of the case records of the JCWB have not survived, due to an institutional policy that they be destroyed after ten years. However, in the remaining files, there are five cases of children who were declared unadoptable for reasons of “mixed racial heritage.” The fact that these records survived suggests such children were far more common than previously thought. The JCWB referred to children from these mixed backgrounds as “mulatto” or “coloured.” In nearly all of these cases, these “unadoptable” children were born to a Jewish mother and a Black father.

Whereas social workers from the JCWB deemed mixed-race babies born to Jewish women unfit for adoption to Montreal’s Jewish families, they viewed children born to Jewish mothers and non-Jewish “white” fathers from Montreal’s Protestant and Catholic communities as adoptable. In these cases, social workers emphasized that such children were Jewish, because they had Jewish mothers. For instance, the JCWB offered “Ms. S” the agency’s services for foster care and adoption should she desire, even though the child’s father was married and Roman Catholic. They even offered legal assistance in establishing the woman’s right to her child, should it be disputed. These adoption regulations suggest that the JCWB, like the broader community, blurred the racial categories of “Jewish” and “white.” These babies were marked as religiously and racially untainted and therefore could be construed as Jewish.

So what happened to these mixed-race children? The archival trail offers scant information. In one case, a mother retrieved her child after she married. In another case, the JCWB sent a four-and-a-half-year-old child to a foster home in Israel. But there is no information about what happened to the remainder of the children. The Venezuelan couple mentioned in the introduction never responded to the offer of a child from a mixed-racial background.

The unplanned pregnancies of single Jewish women, particularly when these pregnancies were the result of interracial or interethnic unions, foregrounds the identity work being done by Jewish institutions. Put slightly differently, the ways in which a father’s race shaped the adoptability of children born to Jewish mothers reveals the complex and racialized construction of Jewishness at midcentury in Canada. This racial history of adoption in the Montreal Jewish community also speaks to how sexuality both reinforced and blurred the boundaries of who counted as Jewish in the postwar period.

Andrea Eidinger is a sessional instructor in the Department of History at the University of British Columbia. She holds a doctorate from the University of Victoria in Canadian history, with an emphasis on the history of gender and ethnicity in postwar Canada. She is also the creator and editor of Unwritten Histories, a blog devoted to revealing hidden histories and the unwritten rules of the historical profession.

Andrea Eidinger is a sessional instructor in the Department of History at the University of British Columbia. She holds a doctorate from the University of Victoria in Canadian history, with an emphasis on the history of gender and ethnicity in postwar Canada. She is also the creator and editor of Unwritten Histories, a blog devoted to revealing hidden histories and the unwritten rules of the historical profession.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com