Moderated by Carolyn Bronstein and Whitney Strub

In honor of the publication of Porno Chic and the Sex Wars, we invited Jennifer Nash, Joe Rubin, Gillian Frank, Carolyn Bronstein, and Whitney Strub to participate in a roundtable on sexual representation in the 1970s United States. In this final round, the contributors discuss some lesser-known texts that shape their understandings of the era. Be sure to check out parts one and two!

Part of the goal in this collection was to move beyond the iconic texts that dominate historical memory of pornography in the 1970s (Deep Throat and Boys in the Sand, for example) and recapture the more diverse, complex pornographies that proliferated, in film, print, and elsewhere. To that end, if you were to select one or two texts to add to the pornographic canon that should help shape how we remember Seventies smut, what would you pick and why?

Joe Rubin

Thanks to an ever increasing interest in the era of theatrical hardcore features, cinephiles and academics have begun exploring a diverse range of films and filmmakers from the 1970s and 80s. Nonetheless, so much of the focus still seems to be on better known and easily accessible works, while more obscure titles, even those directed by established auteurs, have rarely been given the revivals they deserve. If I were able to add two titles to the overall rubric of ‘crucial’ hardcore films, I would select Jerry Douglas’ Both Ways (1975) and Alex deRenzy’s Little Sisters (1972).

Douglas’ film, an exceptionally well-written character drama, traces the double life of Donald Wyman, a well off family man who has taken a secret male lover. Douglas, who had previously explored bisexuality in his play and subsequent screenplay for Score (1972), uses the hardcore feature format to both explicitly present Donald’s sexual exploits and to investigate a subject-matter (male bisexuality) that was basically off limits even in many exploitation films of the period. By working in the realm of “pornography,” Douglas was given a creative freedom to tell a story he deemed important and the result in Both Ways is a stirring drama which forces both its characters and the viewer to confront ideas that are all too often ignored.

DeRenzy’s film is the polar opposite of Douglas’. It is a broad comedy played out almost like a hippie-era fairy tale. Its thin story, of two young girls kidnapped by pirates while their mother tries to locate and rescue them, is merely a framing device for a series of strange and humorous scenarios to play out. Among the eclectic cast of characters are an obese woman and her forest lover, a group of singing drag queens, and an environmentally conscious elf. While deRenzy is fortunate to be among the handful of prolific hardcore filmmakers to have been granted the well-deserved status of an auteur, many of his early features (mostly radically minded and socially progressive documentaries) have remained unavailable, thus denying those interested in exploring his filmography a chance to fully examine the breadth of his career. Sisters has much more in common with the underground films of George Kuchar and John Waters than what many imagine as the sort of formulaic stylings of sex films made around 1972 (the year Deep Throat came out). It serves as a valuable reminder of the extensive ties many pioneering directors of hardcore had to the underground and experimental film and art communities.

Gillian Frank

I love this question because it invites us to think broadly about the range of 1970s texts that aroused desires. My essay for this volume explores Evangelical sex advice manuals for women and places them within an expansive pornographic canon. This inclusion may be surprising for at least two reasons: Evangelicals are widely but mistakenly believed to be anti-sex; and religious sex advice manuals proselytized even as their content was far more than missionary.

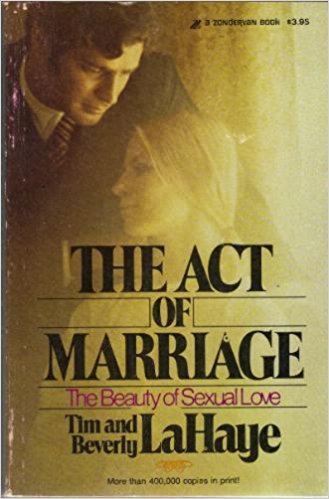

Sex manuals such as Marabel Morgan’s Total Woman (1973) and Tim and Beverly LaHaye’s The Act of Marriage (1976) didn’t just blur the line between pornography and religious genres that speak about sexuality; these text show how the boundaries between pornography and religious sexual forms are probably not as rigid as we think. Consider Morgan’s invitation to women to dress up like “a pixie or a pirate—a cowgirl or a show girl” and to be loud during sex. “Don’t clam up,” she wrote, “The silent-movie days are gone. He’ll respond to your sounds of love.” Hear similar echoes of this injunction for women to perform a vocal and visual sexuality in Tim and Beverly LaHaye’s book: “Chuck your inhibitions. Though modesty is an admirable virtue in a woman, it is out of place in the bedroom.”

Or consider the frankness with which the LaHayes explained to women how they might make their man climax.

Gently massaging the genital region, she should run her fingers over his penis, pubic hair, scrotum and inner thighs. She should be very careful not to put pressure on his testicles located inside his scrotal sac, as this can be quite uncomfortable. With her hand around the shaft of the penis, she should begin massaging up and down. As her motion becomes more rapid, her husband’s body will grow more rigid, and she will be able to verify his response to her touch. This motion should be continued until he ejaculates. Before beginning this exercise, the wife should have several tissues on hand to absorb the discharge.

The LaHaye’s encouraged mutual masturbation, extensive foreplay, and a range of sexual positions for married heterosexual couples. And although their prose is far from breathless, one can hardly ignore its potential to arouse a solitary reader. The act of reading sexual advice could engender pornographic pleasure regardless of the reader’s motivation for seeking out the information.

In short, I would invite us to consider how a number of religious texts, even ones that disavow sexual expression, can be explicit, graphic and productive sites for fantasy and desire.

Jennifer Nash

My interest remains in thinking about the place of black erotics on the 1970s pornographic screen, and this commitment informs my choices. Because of my ongoing preoccupation with Desiree West, and with archiving hardcore’s first black female star, I’d suggest placing Sexworld (1978) in the canon. With its elaborate narrative focusing on the potential pleasure of technology to unleash unknown or otherwise repressed sexual longings, and its representation of its black female protagonist playfully inhabiting racial stereotype, it remains—at least to me– a fascinating piece of the 1970s porn archive. I would also love to see more scholarly and popular attention to Lialeh – a 1974 film where the aesthetics of porn and Blaxploitation meet (in my book, I call it the blax-porn-tation aesthetic). With its cool soulful soundtrack (performed by Bernard Purdie), and its investment in sexual autonomy as a practice of black freedom, Lialeh invites scholars (and fans) to think about the collaborations between pornography and other genres. Lialeh is also fascinating because it disrupts the oft-rehearsed scholarly periodization that it was the 1980s that saw the birth of the all-black film.

Whit Strub

Central to the ways Carolyn and I conceived Porno Chic and the Sex Wars was emphasizing the different media forms that pornography took, so for these closing remarks, I’ll take film and she will discuss print media. For my part, I’d like not only porn studies scholars, but also film scholars and cultural and urban historians more generally, to give pornography more serious attention as a defining feature of the terrain they purport to cover; you really can’t do full justice to those topics without acknowledging its sheer pervasiveness. So when film historians think about the almost fetishistic use of location shooting (a sort of “money shot” in its own way, when it came to proving bona fides in an idealized gritty authenticity) of the New Hollywood, they should also account for the fact that hardcore filmmakers often outdid the Scorseses, De Palmas, and Friedkins when it came to really exploring the urban landscape. I also think it’s incumbent upon scholars in those fields to think about both straight and queer representations, and to that end, I’d nominate Jerry Douglas’ The Back Row (1972) and Shaun Costello’s Fiona on Fire (1978) as exemplars of this urban-porno style. Douglas’ film charts a cartography of desire, following a gay couple as they cruise one another across Manhattan, carefully noting the specific places—Times Square, Washington Square park, porn theaters, etc.—that facilitate their courtship, and gay eros itself. Costello’s film, a dark riff on the classic film noir Laura (1944), contains some of the misogynist violence very typical of hetero-porn of its era, but also depicts a rich urban social world rife with both pleasure and danger.

Indeed, the talented and prolific Costello’s immense body of work, largely ignored by scholars until very recently, points toward the yet-unwritten histories of pornography that await further work. Laura Helen Marks’ essay on his funny, unsettling Dickens adaptation The Passions of Carol (1975) in Porno Chic, as well as Neil Jackson’s article on his controversial rape-driven thriller Forced Entry (1972) in a recent Porn Studies dossier on “Canon Fodder” edited by David Church (to which I contributed an essay on Bacchanale {1970}, an ostensibly straight early hardcore feature directed by two gay brothers), suggest directions for future scholarship—there are numerous such creative, idiosyncratic filmmakers in hardcore history who deserve rediscovery, from Anthony Spinelli to Roberta Findlay. While some have passed away, often leaving little in the way of archives, others are around and accessible: Jerry Douglas is donating his papers to NYU, and Costello blogs parts of his memoirs of the era (along with recipes, polemics, and more), which complements recent autobiographies by other porno culture-workers such as director Larry Revene and actor Howie Gordon. Scholars make insufficient use of these, but they are rich, valuable texts—as are the essays and oral histories on the deeply researched Rialto Report. Let’s stop imagining that 1970s hardcore began and ended with Deep Throat!

Carolyn Bronstein

Reading through these comments, and thinking about the overall intent of the Porno Chic and the Sex Wars collection, I want this closing comment to emphasize the diversity of sexual communities that 1970s pornographies served. This is such an important historical and contemporary aspect of pornography that does not get sufficient attention, and is often overlooked when people evaluate “pornography” as a whole. A good case in point here is the February 10, 2018 anti-porn op-ed penned by conservative columnist Ross Douthat for the New York Times. Insisting that hard-core porn ought to be something that we are forced to quest after like criminals “in dark corners,” Douthat conjures images of “online gangbangs” and anal sex and argues that these exposures are destroying the hearts and minds of our youth. Of course, this charge has been leveled at popular culture for decades, from the ruinous lewd dancing taking place in early 20thcentury dance halls to the sexually explicit 1980s song lyrics of Prince and Madonna, both targeted for censorship by the Parents’ Music Resource Center. Those who object to pornography, a narrative that has been relatively constant since the 1950s, frequently fail to consider how its messages and images can inform, empower and include those on the margins. Campaigners for Charles Keating’s Citizens for Decent Literature saw only moral degeneracy in the Beebo Brinker lesbian pulp novels written by Ann Bannon between 1957 and 1962, whereas those with a more progressive view saw the stories’ optimistic endings as paving the way for social acceptance of lesbianism and a gay rights revolution.

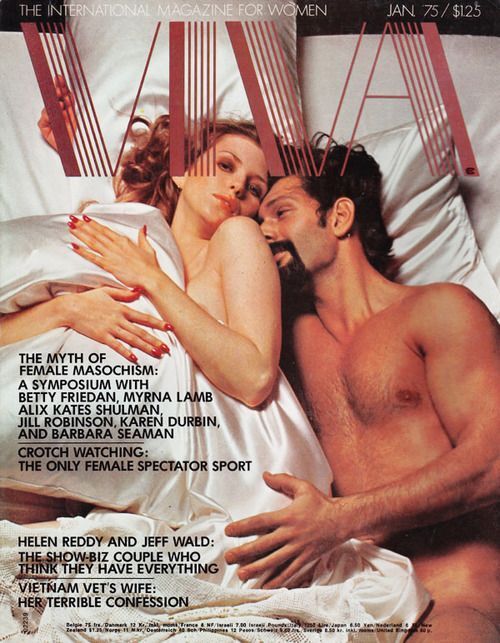

In the Porno Chic collection, Whit and I consciously included scholarship that expanded our knowledge of 1970s-era pornography for non-traditional audiences. We recognized that print media were easier to acquire and enjoy in private settings than films in the pre-videocassette player years, and we conceptualized pornography broadly as material that united or helped shape erotic communities. As Gill has discussed above, the marriage manuals written for Evangelical Christians were an attempt to bring religious, conservative Americans into the sexual revolution. It was impossible to ignore the social impact of advice books like Alex Comfort’s The Joy of Sex (1972), which spent eleven weeks in the top spot of the New York Times’ best seller list and more than 70 weeks in the top five. Nancy Friday’s My Secret Garden: Women’s Sexual Fantasies (1973) offered a groundbreaking catalog of women’s desires. Sharing what had previously been considered taboo, Friday was dismayed by the extent of female sexual repression and lamented “that women today, at the turn of the century, would still think they were the only Bad Girls with erotic thoughts.” Christian marriage manuals did not challenge the sexualization of American culture, nor try to turn back the tide, but rather sought a way for devout husbands and wives to participate.

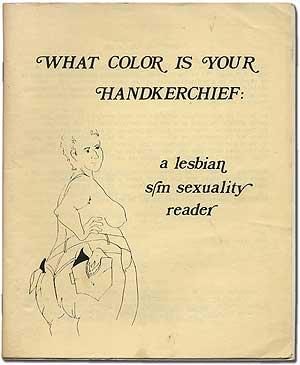

At the same time, pornography played an important role in establishing visible erotic communities for sexual minorities. Alex Warner wrote in Porno Chic about the sexual guides What Color is Your Handkerchief? (1979) and Coming to Power (1981) by the San Francisco Bay Area SAMOIS collective, which announced the existence of a vibrant lesbian SM community. Inviting and encouraging, these books explained the rules and conventions of SM play to the uninitiated and provided information about area meet-ups and gay bars where one could see an SM demonstration and find sexual partners. Nicholas Matte wrote about the circulation of trans print publications like FI News, noting that these publications did community-building work helping trans people and the trans amorous find one another for social, political and sexual purposes. The realities of market-driven, mass pornography also encouraged the fetishization of trans people, but the visibility provided by the community-minded publications was an important first step toward liberation. My hope as we consider pornography in the 1970s and in today’s contemporary contexts, is that we remember the diversity of subject matter and users, rather than focusing on the worst exemplars and calling for bans and censorship.

Carolyn Bronstein is the Vincent de Paul Professor of Media Studies in the College of Communication at DePaul University, and an affiliated faculty member in the Department of History and the American Studies Program. She is the author of Battling Pornography: The American Feminist Anti-Pornography Movement, 1976-1986 (Cambridge, 2011) and coeditor with Whitney Strub of Porno Chic and the Sex Wars: American Sexual Representation in the 1970s (University of Massachusetts, 2016).

Gillian Frank co-hosts Sexing History. He is a Postdoctoral Fellow in the American Studies Program at the University of Virginia. Frank’s research on sexuality, race and religion in the twentieth-century United States has appeared in Gender and History, Journal of the History of Sexuality and Journal of Religion and Popular Culture. He is currently working on a book entitled Making Choice Sacred: Liberal Religion and Reproductive Politics in the United States Before Roe v Wade. Gillian tweets from @1gillianfrank1.

Jennifer C. Nash is an Associate Professor of African American Studies and Gender & Sexuality Studies at Northwestern University. She is the author of The Black Body in Ecstasy: Reading Race, Reading Pornography (Duke University Press, 2014), which was awarded the Alan Bray Prize by the GL/Q Caucus of the Modern Language Association. She is also the editor of Gender: Love (Macmillan). She has published in journals including GLQ, Social Text, Feminist Theory, and Feminist Review.

Joe Rubin is an American film archivist and co-founder of the acclaimed home video company, Vinegar Syndrome. His work to restore and preserve American hardcore feature films has been featured in The New York Times, Playboy, The Village Voice, and elsewhere.

Whitney Strub is an Associate Professor of History and director of the Women’s & Gender Studies program at Rutgers University, Newark. He co-directs the Queer Newark Oral History Project. He is the author of Perversion for Profit: The Politics of Pornography and the Rise of the New Right (Columbia, 2011), and Obscenity Rules: Roth v. United States and the Long Struggle over Sexual Expression, and he blogs about Newark, film, and queer history.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com

Fascinating post, thanks to all the different and diverse people writing!