Julio Cesar Capó, Jr

Welcome to Fairyland is a transnational queer history of a relatively new city (Miami proper was incorporated as a city in just 1896). In paying particular attention to how constructions of gender, sexuality, race, ethnicity, class, age, ability, and nation collided in the city and beyond from the 1890s to 1940, the book explores the conditions in which certain practices, behaviors, and ideologies became normative and others were policed and categorized as perverse, unnatural, and criminal.

This transnational urban history disrupts a nation-state-driven narrative by emphasizing how Miami was a contested colonial space. It highlights the central role that migration, trade, and tourism to and from the Caribbean played in shaping that which became normative and that which became transgressive in the city. It traces the lives of people who engaged in same-sex sexual acts, those who partook in interracial encounters, migrants and immigrants policed at the borders and city, tourists and slummers, sex workers, male and female impersonators, queer entertainers, and mannish and modern women. They all worked in creative ways to carve out a space of their own in the city white urban boosters heavily promoted as “Fairyland.” In this way, the book explores the textured and varied meanings of “Fairyland,” as the moniker came to represent radically different things to discrete groups of people.

NOTCHES: What drew you to this topic?

Capó: Well, I guess the most immediate answer is that I’m from Miami and I have always been both really interested in learning more about its history and development. I’ve also been a bit frustrated by the lack of real scholarly attention paid to this city. So, this project interested me very deeply on both a personal and professional level. I have also long wanted to see the fields of queer history and sexuality history really push the limits of national and urban history by adopting a transnational framework in their analysis of the past; in particular, I wanted to see the fields highlight and elevate the experiences and voices of people of color who had been left out of far too many narratives. I also trusted my deep skepticism that the so-called silences of the archives were a foregone conclusion that rendered some histories unknowable or untraceable. In this way, I think the influences of my other areas of specialty—particularly the fields of (im)migration, ethnicity and race, Caribbean, and Latinx studies—are very much coming together in this work. Certainly, studying Miami allowed me to make several of these key connections and to demonstrate how colonial and imperialist projects proved central to shaping how norms have been constructed over time and how they shaped queer subjectivities in the city and beyond.

Clearly, most of the questions I was asking when I first undertook this project had long consumed me and I felt they merited greater attention and exploration. I think in that way I sought to bridge the several histories and fields I had long engaged in, as they all seem to come together in productive ways in my exploration of Miami’s past. How could we understand the municipal incorporation of Miami independent of the War of 1898, for instance, or how do we study the end of Prohibition in Miami and the United States without factoring the effects of a massive revolution in nearby Cuba that same year? Or, more broadly, how could we fully appreciate the significance of the greater public visibility of homosexuality in the urban landscape without a clearer understanding of the racialized and surprisingly queer origins of bourgeoning heterosexual identities and consumer cultures?

Although Welcome to Fairyland is my first book, this project was realized in a slightly less traditional way in that it wasn’t based on my dissertation research. My dissertation project looked to queer Miami in the post-World War II era and it highlighted the role that queer immigrants, in particular, played in shaping sexual and racial politics during the Cold War era. As I began revising my dissertation during my postdoc, I realized I first needed to set the foundation for that project by conducting more primary research on Miami’s early years; after all, it was quite different from the major cities we already knew quite a bit about for the early twentieth century like New York or San Francisco. At first, I thought I would write a new chapter or two to set up queer life in early Miami, but when I revisited the archives to do just that, I found evidence that challenged much of what I thought I knew about this earlier period and decided to explore it further. In doing so, I found rich evidence that indeed challenged long-established narratives and periodizations in queer history alongside our understanding of tourism, transnationalism, the Caribbean (particularly the Bahamas, Cuba, and Haiti), the U.S. South, and urbanization. The evidence took me on a very different and I thought very exciting path. By the 1940s, one can see clearer signs of more legible and public communities in Miami that came together at least in part through their gender and sexual difference, particularly the former. I will continue to engage several of these questions, themes, and frameworks—as well as many new ones—in my next monograph, which is a revision on my dissertation project. Tentatively titled A Queer Refuge: Miami after World War II, that work explores the role Miami’s racial and ethnic communities played in affecting social and political change in an era of growing LGBT politics.

NOTCHES: This book is clearly about the history of sex and sexuality, but what other themes does it speak to?

Capó: One of the things I hope readers take away from Welcome to Fairyland is how embedded histories of gender and sexuality are in shaping the world around us. Any exploration of changing meanings of gender and sexual expression must fundamentally engage with questions of race, ethnicity, class, age, ability, and nation. While my book certainly offers new insight in queer and sexuality history, I hope it also reorients some of the ways we think about (im)migration, urbanization, tourism, trade, colonialism, and race relations in the United States and parts of the Caribbean.

NOTCHES: How did you research the book? (What sources did you use, were there any especially exciting discoveries, or any particular challenges, etc.?)

Capó: In adopting a transnational framework, my archives also existed outside of the United States. While I did research in archives and research depositories throughout Florida and other parts of the United States, the National Archives of the Bahamas proved critical to my analysis. To a smaller extent, I also relied on research I had conducted in Cuba and Haiti for my work on post-WWII queer Miami to document the changes that occurred after the 1940s in the book’s epilogue.

My source base was pretty varied and often quite unique; I found evidence in some traditional sources, but there were also several surprises that really inspired me to explore new ways of thinking about what constitutes a historical archive. I looked to criminal records, immigration logs, colonial sources and correspondence from the Bahamas, letters, court cases, and newspaper accounts that I, at times, coupled with evidence culled from films, songs and sheet music, literature, poetry, paintings and artistic renderings, postcards, staged performances, advertisements, and even everyday objects like matchbooks or a piggybank.

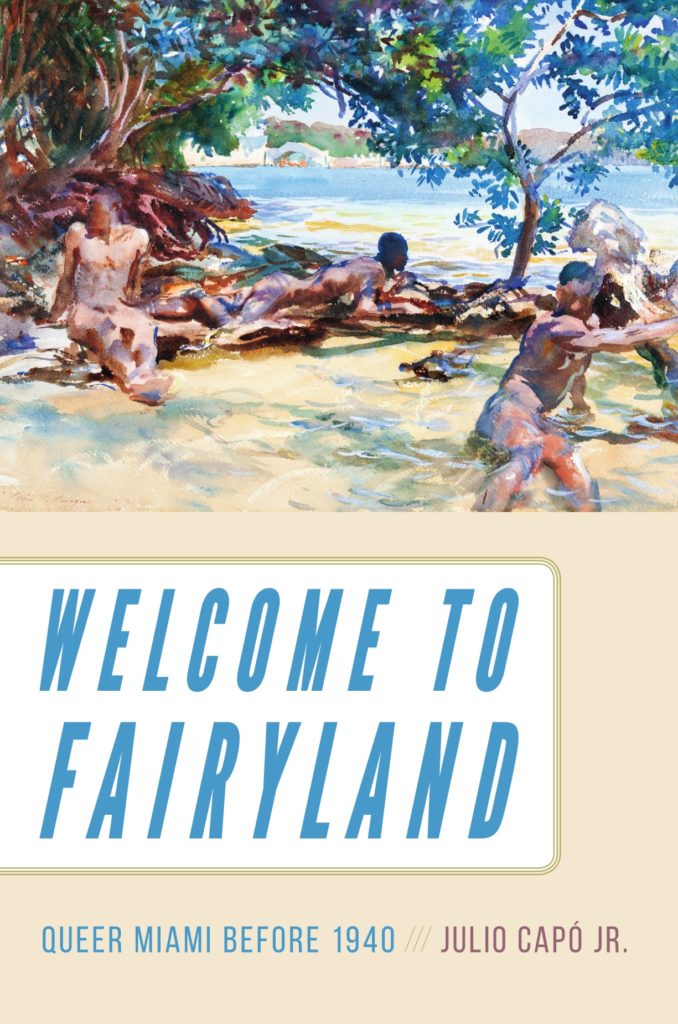

I was really drawn to two sources in particular. I found a great deal of inspiration in some of the paintings that famed artist John Singer Sargent created during his visit to Miami in 1917. I linked these to the creation of a racialized queer erotic in the city, just as a disproportionate number of Bahamians were accused of sodomy and other sexual crimes. I was also really fascinated by a piggy bank from the late 1930s or early 1940s I found in the likeness of “Mother Kelly,” who was a gender-bending entertainer and operator of an eponymous nightspot in the area. The piggy bank was incredibly playful and tongue-in-cheek in its strategic placement of the coin slot, which clearly allowed people to imagine what else might penetrate Mother Kelly’s rear side.

NOTCHES: Your book is published, what next?

Capó: Before I entered graduate school I worked as a journalist writing and producing the morning news. I have always been really interested in finding ways of making sense of our world today with a keen understanding of how the past took shape and what we stand to learn from those experiences.

I’ve been writing about queer Latina/o/x and immigrant issues for over a decade now and when the Pulse nightclub massacre devastated our world in June 2016, I shared the anger, frustration, and the overwhelming feeling of loss and despair so many others felt and still feel. The vast majority of those who lost their lives that night were queer Latinx; the massacre was indeed a manifestation of violence that was decades in the making. I am writing a book that places Pulse in the long history of violence, erasure, and displacement of Latinx and queer folks. How can we understand the tragedy at Pulse, for instance, independent from the United States’s neoliberal experiments in Puerto Rico that sparked numerous waves of migration, or the effects of gentrification on queers and people of color? I’m not telling the story of what took place at that gay club that night, but rather how the events of Pulse fit into a much longer history we must directly engage with as we continue to fight for social justice. When I complete that book, I’ll return my focus on queer Miami in the post-World War II era and revise my dissertation for publication.

Julio Cesar Capó, Jr. is Associate Professor of History and the Commonwealth Honors College at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. Capó researches inter-American histories, with a focus on queer, Latinx, race, (im)migration, and empire studies. His book, Welcome to Fairyland: Queer Miami before 1940 (University of North Carolina Press, 2017), has received six honors, including the Charles S. Sydnor Award from the Southern Historical Association recognizing the best book in Southern history. Capó’s work has appeared in the Journal of American History, Radical History Review, Diplomatic History, and Journal of American Ethnic History, with a forthcoming piece in Modern American History. A former journalist, he has also written for Time, The Washington Post, The Miami Herald, and other outlets. He is co-chair of the Committee on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual & Transgender History and has held fellowships at Yale University and the United States Studies Centre at the University of Sydney.

Julio Cesar Capó, Jr. is Associate Professor of History and the Commonwealth Honors College at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. Capó researches inter-American histories, with a focus on queer, Latinx, race, (im)migration, and empire studies. His book, Welcome to Fairyland: Queer Miami before 1940 (University of North Carolina Press, 2017), has received six honors, including the Charles S. Sydnor Award from the Southern Historical Association recognizing the best book in Southern history. Capó’s work has appeared in the Journal of American History, Radical History Review, Diplomatic History, and Journal of American Ethnic History, with a forthcoming piece in Modern American History. A former journalist, he has also written for Time, The Washington Post, The Miami Herald, and other outlets. He is co-chair of the Committee on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual & Transgender History and has held fellowships at Yale University and the United States Studies Centre at the University of Sydney.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com