Bob Cant and Kieran Rose

Bob Cant, a long-time contributor to NOTCHES, joined Kieran Rose, former co-chair of GLEN (Gay and Lesbian Equality Network), in conversation about trade union involvement in the campaigns for lesbian and gay rights in Ireland between 1981 and 1993. Bob and Kieran first met in 1995 when Kieran went to Edinburgh to speak at a meeting during Pride Scotland about lesbian and gay campaigning in small nations. NOTCHES is delighted to share their conversation here.

Bob Cant: The changes that have taken place in Ireland recently in relation to the treatment of LGBT people have been enormous. Ireland long had a reputation as something of a backwater in Europe, and the referendum in 2015 on marriage equality took the whole world by surprise. Such changes, however, did not simply drop from the sky, and I want to go back forty years to the early stages of the campaigns to reform Irish laws in relation to homosexuality. You were particularly involved in the trade union movement, and I would like you to tell us more about your expectations of the trade unions in the early 1980s.

Kieran Rose: The situation for LGBT people in Ireland has been transformed in recent decades from being one of the most repressive to one of the most progressive countries on LGBT issues in the world. The trade unions were our crucial allies from the 1980s on when we had few, if any, such powerful supporters and many influential opponents. The British anti-gay laws had not been abolished on independence in 1922, and the Bishops in the Catholic Church had doggedly and strenuously opposed any attempts at progress for lesbians and gay men. The lesbian and gay movement was quite weak at the time, with few resources and few activists (many emigrated because of very high unemployment at the time). So, trade union support was vital.

The 1980s in Ireland was a torrid time for progressives. The Right was all-powerful, winning two referendums—on abortion (1983) and divorce (1986)—and the Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of the criminalisation of gay sex. The Left and progressives were dispirited by the litany of defeats and by the economic crisis, massive unemployment, and emigration. JJ Lee, the historian and former Senator, has written of how we were ‘stumbling towards the future with tragedy in the North and gloom in the South’.

Many of the lesbian and gay activists in the 1980s were socialists, at least on the Left, and so it was natural for us to be activists in our unions and to look to them for support. I put a motion to the Cork Branch of the Local Government and Public Services Union (LGPSU) in 1982 calling for gay law reform and the inclusion of sexual orientation in the unfair dismissals and employment equality legislation. The motion was later passed overwhelmingly by the union at the national level and set the agenda for the next decade or so.

The Irish Congress of Trade Unions (ICTU) passed a similar motion in 1982, and we then set about getting ICTU to take action to implement the policy. LGPSU and the Irish Distributive and Administrative Trade Union (IDATU), the retail workers union, pushed very hard, against some resistance, to get progress at ICTU level.

In 1987, ICTU published a radical policy document, ‘Lesbian and Gay Rights in the Workplace’. This policy, and the strong support of ICTU and individual unions, was crucial in the achievement of an equality-based gay law reform and inclusion of sexual orientation in the Unfair Dismissals Act in 1993.

Cant: What attitudes were there within the lesbian and gay communities and movement to the possibility of working inside/alongside the trade union movement?

Rose: I think there was overwhelming enthusiasm for working closely with the trade union movement. There is, I think, a tradition of popular support for the trade union movement in Ireland, partly due to its role in the struggle for independence, the memory of the 1913 lockout, protecting the underdog against powerful vested interests, and so on, and we were part of that popular support. One of the key workshops at the First National Gay Conference in Connolly Hall (a trade union conference centre) in Cork in 1981 was the one on working with the trade unions, and the strategy adopted then set the agenda for the next decade or so.

One of the problems for us at the time was that many lesbian and gay activists were unemployed, or in precarious employment, and so often not eligible to join trade unions. In 1982, lesbians, gay men, and others set up the Quay Co-op (a workers’ co-op) in Cork, a bookshop, a cafe, a resource centre. This allowed them to join IDATU and to work within the union to gain support. IDATU and its General Secretary, John Mitchell, were key allies in getting ICTU to take action. Around that time, IDATU members in Dunnes Stores were on strike for refusing to sell products from apartheid South Africa and getting great support from IDATU and John Mitchell.

One of the reasons why lesbians and gay men were so supportive of trade unions was that they were so strongly and publicly supportive of us when our jobs were at risk. A good example of this arose from the scandal at the Kincora Boys Home in Northern Ireland, which was a murky story of child abuse, allegations of security services collusion, and cover ups. When the health board decided to fire all lesbian and gay workers, this purge was resisted by the union, Northern Ireland Public Service Alliance (NIPSA ), particularly one of its officials, Laurence Pimley, and the health board backed down. Jeffrey Dudgeon in 2012 described the huge role of Laurence as ‘heroic’.

In the Republic in 1988, Christopher Robson and his union, Union of Professional and Technical Civil Servants (UPTCS), negotiated a ground breaking equality agreement with the Civil Service that stated that discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation or medical condition, including HIV/AIDS status, ‘would not be tolerated’. This policy was then rolled out to the rest of the public sector, ironic given that we were still criminals in the eyes of the State.

It was ironic, too, that other civil servants around the same time were opposed to funding of Gay Health Action (GHA) workers on the basis that it was promoting safer sex practices, and that as gay sex was criminal it would be contrary to ‘public policy’. At a meeting with the Minister for Labour, Bertie Ahern (later to be Taoiseach, or Prime Minister, and a key player in the Peace Process who was also a former trade union activist), the trade unions strongly supported funding for GHA workers. Bertie Ahern paused the meeting to talk to his civil servants separately and, when the meeting with the trade union officials resumed, the funding for GHA was agreed. Apparently, in his private meeting with his civil servants, Bertie Ahern said: ‘Ah, come off it, lads, we can’t be refusing this funding.’

The high-profile media coverage of trade union support also shaped the narrative around our campaign as being about equality, civil rights and workers’ rights, and about fairness. This narrative was key in all our later successes, including the marriage-like Civil Partnership Act of 2010 and the victory in the marriage equality referendum of 2015, where trade unions again played a key role. This public and practical solidarity was also a great morale boost for us at a time when we felt quite beleaguered, especially in the 1980s. No wonder we were so enthusiastic about working with and supporting the trade union movement.

Cant: One of the things which interests me about the reforms of 1993—and perhaps you could briefly spell them out—is the fact that they went much further than just de-criminalisation of homosexual activity in the way that was the case in different parts of the UK and also in other countries. Was the fact that Ireland is a small country part of the reason for that? Can you tell us more about the whole focus on equality?

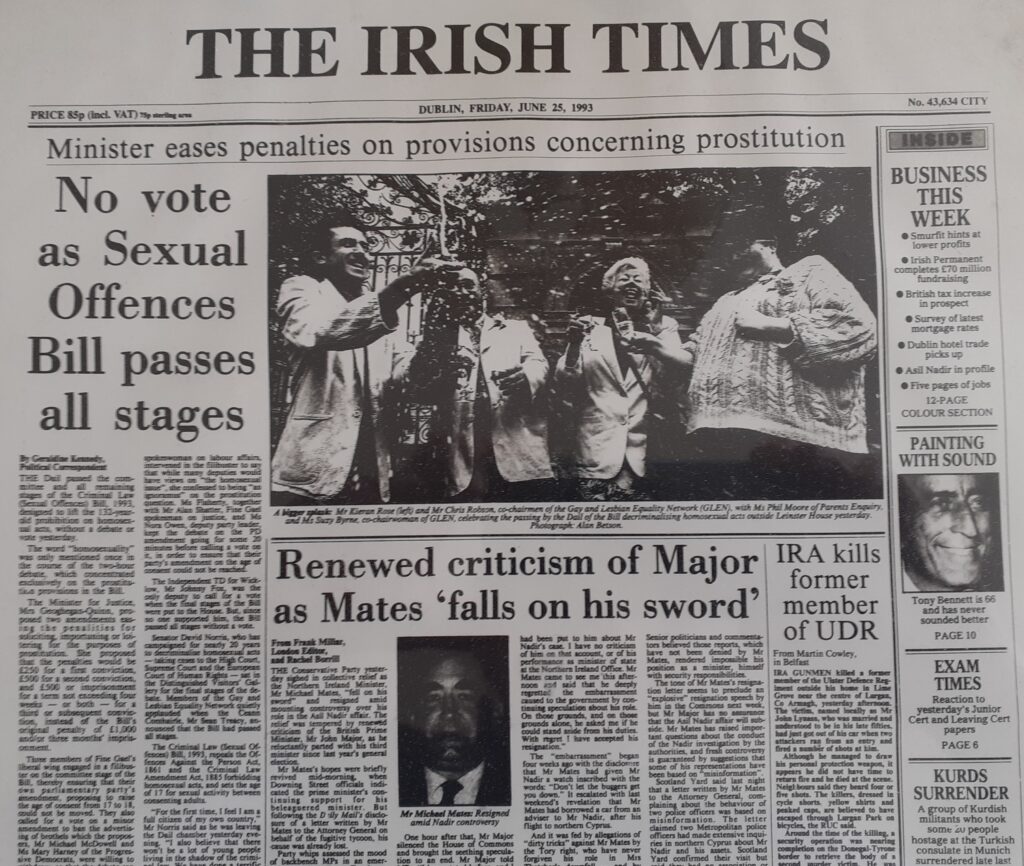

Rose: When the Gay and Lesbian Network (GLEN) was set up in 1988, it made a deliberate strategic decision to take a broad equality-based approach. Not only did we focus on demands in relation to sexual law reform, but we also included socio-economic demands, in terms of general equality legislation and inclusion of sexual orientation within the terms of the Unfair Dismissals Act. The equality and work-related objectives were not surprising as Christopher Robson and myself were both co-chairs of GLEN and also trade union activists.

While we actively studied the lesbian and gay campaigns in other countries, we knew that we would have to adapt them to suit the particular circumstances and history of Ireland, its particular barriers and opportunities. In an article in Lesbian and Gay Visions of Ireland (1996), I wrote that if ‘the political projects developed in other countries in such radically different circumstances were transferred to Ireland, unthinking and undigested, without regard to the particular problems and opportunities that existed here, they would have been almost bound to have failed.’

The twin aims supported one another. Gay law reform was high on the political agenda and in the media. Following a decade-long legal case initiated by David Norris, the European Court of Human Rights in 1988 decreed that the criminalisation of homosexual activity was a breach of privacy. The government had to repeal the law, and so this gave us an opportunity to promote the wider equality and human rights agenda. The Right wanted to focus the debate on gay law reform around buggery and disease; we wanted the debate to be around equality, human rights, and fairness.

We set up the Campaign for Equality in the early 1990s, a coalition of various groups such as trade unions, women’s organisations, and people with disabilities to support GLEN’s twin demands including wide-ranging equality legislation to protect and promote the rights of all groups vulnerable to discrimination.

One of the advantages of a small country is that people and groups representing different sectors know one another and work together. Practically, groups had to work together because most had few resources. Christopher Robson and myself worked with the Irish Council for Civil Liberties on their 1990 book, Equality Now for Lesbians and Gay Men, making the intellectual case for an equality-based law reform and equality legislation including various groups. It also called for legal recognition for lesbian and gay couples. We persuaded the Labour Party to publish an Equal Status Bill that included sexual orientation in 1990 and, with Labour in a coalition government in the mid-1990s, this type of legislation was enacted, setting up an implementation body, the Equality Authority (following merger it is now the Irish Human Rights and Equality Commission). Lesbian and Gay Rights at Work was an informal group of trade unionists in the 1980s, and one of our successes was to convince the Board of Employment Equality Agency to call for its remit to be extended beyond gender and marital status to include sexual orientation and other grounds.

For GLEN it was all about making equality a reality in people’s everyday lives. When homosexual activity was de-criminalised in 1993, the commitment to equality ensured that there was an equal age of consent and an equal right to privacy for both homosexual and heterosexual activity. At the height of our lobbying campaign in 1992, we made a proposal to the Combat Poverty Agency to carry out a study on issues of poverty and discrimination and lesbians and gay men. This study, ‘Poverty: Lesbians and Gay Men: The Economic and Social Effects of Discrimination’, was published in 1995, a fairly unique analysis at the time.

Cant: There is sometimes a complacency that sees Ireland is as being largely within the shadow of the UK; developments in lesbian and gay rights are often perceived as following on from the example of its larger neighbour. What your story shows us is that a small nation can draw upon its own history and its own traditions in such a way as to embed lesbian and gay rights securely in its national narrative.

Bob Cant has been a teacher, a trade unionist, a community development worker in Edinburgh, a Haringey activist and an editor of several collections of LGBT oral history. He now lives in Brighton and his first novel, Something Chronic, was published in 2013. Bob tweets from @bobchronic

Bob Cant has been a teacher, a trade unionist, a community development worker in Edinburgh, a Haringey activist and an editor of several collections of LGBT oral history. He now lives in Brighton and his first novel, Something Chronic, was published in 2013. Bob tweets from @bobchronic

Kieran Rose has been a gay activist and trade unionist since early 1980s. He was a co-founder of GLEN the Irish Gay and Lesbian Equality Network in 1988 and was involved in all key progress: gay law reform (1993), equality legislation (1998), civil partnership (2010), and civil marriage equality (2015). He was appointed as a Commissioner of the Irish Human Rights and Equality Commission in 2014 by the President of Ireland Michael D. Higgins. Kieran wrote Diverse Communities: The Evolution of Lesbian and Gay Politics in Ireland (1994). He tweets from @kieranarose

Kieran Rose has been a gay activist and trade unionist since early 1980s. He was a co-founder of GLEN the Irish Gay and Lesbian Equality Network in 1988 and was involved in all key progress: gay law reform (1993), equality legislation (1998), civil partnership (2010), and civil marriage equality (2015). He was appointed as a Commissioner of the Irish Human Rights and Equality Commission in 2014 by the President of Ireland Michael D. Higgins. Kieran wrote Diverse Communities: The Evolution of Lesbian and Gay Politics in Ireland (1994). He tweets from @kieranarose

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com

5 Comments