Alison Clark Efford and Viktorija Bilić

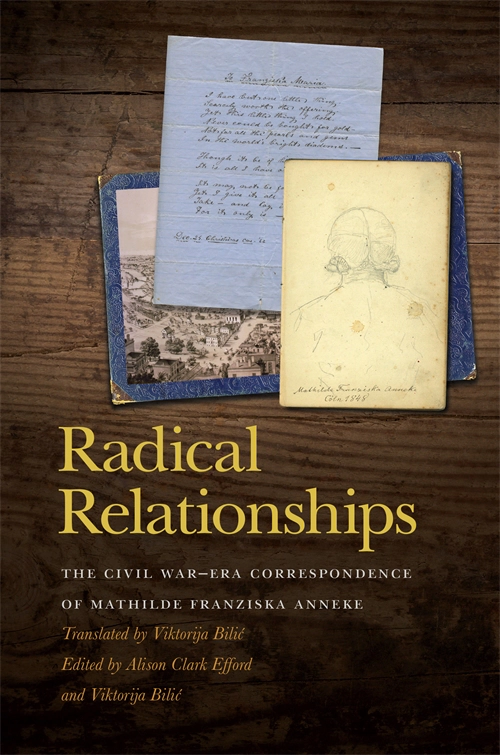

Radical Relationships presents a selection of edited, translated letters that narrate the intense, cohabiting “romantic friendship” between German American feminist Mathilde Franziska Anneke and Anglo-American abolitionist Mary Booth from 1859 to 1865.

NOTCHES: In a few sentences, what is your book about? Why will people want to read your book?

The letters documenting Mathilde Franziska Anneke and Mary Booth’s relationship provide a remarkable resource for queering nineteenth-century romantic friendships between women. Historians have written about such relationships before, but this set of correspondence emphasizes a quality that remains elusive: The fact that romantic friendships were not constrained by today’s categories of lesbian or straight, sexual or platonic. Mathilde and Mary did not identify as lesbians, and we do not know what they did in bed, but “just friends” hardly captures their passion or household dynamics.

Historians of sexuality will also be interested in the women’s response to the trial of Mary’s husband Sherman Booth for “seducing” (raping) a fourteen-year-old.

In addition to the themes, the book has an extraordinary narrative arc. Mathilde and Mary participated in an attempted jailbreak, international travel, the machinations of leading European radicals, and the fallout from the court martial of Mathilde’s husband, all before their relationship was cut tragically short.

NOTCHES: Your book is a collaboration. Who did what?

Neither of us could have pulled off this project alone. The historical research influenced the translations, and the translations influenced the historical analysis.

Viktorija, an expert translator, was responsible for translating the German letters into English. I (Alison) researched and wrote most of the footnotes and main introductions, while keeping an eye on narrative and thematic concerns as we selected the letters to include. But that characterization of the division of labor hardly reflects the intertwined nature of our collaboration. We consulted each other and revised each other’s work every step of the way.

NOTCHES: What drew you to this topic, and what questions do you still have?

I read some of Mathilde’s letters in the archive when I was working on my first book and was captivated. They are plentiful, revealing, and cover dramatic events and powerful feelings. Mathilde is not unknown. She fought in the German Revolutions of 1848–1849, published the first woman-run feminist periodical in the United States, and became an important US suffragist. But her letters are in German in the old Kurrentschrift, so they are not particularly accessible, even to German-speaking researchers.

I suggested the project to Viktorija. She immediately saw the potential for a partnership that would advance the practice of historical translation through collaborative work that involved the historian and the translator as a team.

In terms of remaining questions, I recently learned that Andi Zimmerman at George Washington University is working on queering nineteenth-century communism. Their ideas have piqued my interest in Mathilde’s place among the German radicals who were involved in the 1848 revolutions and also resisted heteronormative family structures.

NOTCHES: This book engages with themes of sex and sexuality, but what other themes does it speak to?

It provides a window into transatlantic radicalism at the time of the US Civil War, showing how migration, feminism, abolitionism, socialism, and military service related to each other.

NOTCHES: How did you research the book? What especially exciting research discoveries did you have?

The Anneke Family Papers are housed close to us at the Wisconsin Historical Society, but contextualizing the letters required researching farther afield. Viktorija spent time in German archives to place Mathilde in her German literary context, clear up confusing references, and create a corpus of parallel texts for the task of translation. We had a great time traveling to Zurich together to track down the specifics of Mathilde and Mary’s life in the Swiss city between 1860 and 1864.

Everything about the research surprised us! I knew that the women expressed their love for each other effusively, but I didn’t expect jealousy to surface as it did. I had no idea the letters would reference Sherman Booth’s rape trial. Mathilde and Mary clearly thought he was guilty, but they wouldn’t publicly support the girl he raped. Nevertheless, Mathilde still decided to help organize an armed attempt to break Sherman out of jail when he was imprisoned for his abolitionist activity—another surprise. The correspondence also included material on the personal lives of German radicals living in Zurich, and Mathilde and Mary wrote a lot about health and parenting.

NOTCHES: What stories were left out of the book?

The book’s strength and its weakness is its narrow focus. I would love to be able to compare Mathilde and Mary’s romantic friendship to other relationships: between men and between women of different backgrounds. Although Mathilde and Mary were often desperately poor, they were white, middle-class, educated, and respected. They wrote about African Americans, but did not interact with people who were not white.

NOTCHES: How do you see your book being used most effectively in the classroom?

The book provides accessible and engaging primary sources that students can use to reflect on queer lives in the nineteenth century and the limitations of the ways we categorize relationships today. I would pair it with Carroll Smith-Rosenberg’s “The Female World of Love and Ritual” in Signs (1975!) or excerpts from Martha Vicinius’s Intimate Friends, Saidiya Hartman’s Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments, or Matt Brin’s Poor Queer Studies. Students might use the letters to compare and evaluate different characterizations of the Mathilde-Mary relationship such as Chapter 4 of Mischa Honeck’s We Are the Revolutionists and Joey Horsman’s “A German American Feminist and Her Female Marriages: Mathilde Franziska Anneke, 1817–1884” on Fembio. (Interested instructors can find open-access teaching materials on Radical Relationships on the press website.)

NOTCHES: Why does this history matter today?

I hope lesbians continue to claim nineteenth-century romantic friendship as part of their history, but it can inspire other people too. Working on the book has given me an inspiring sense of how relationships can resist commonly accepted categories. Broadening our understanding of the intimate connections that come with excitement and support is potentially powerful. Especially in the midst of a global pandemic, women’s friendships can save us when institutions fail and empower us to change institutions for the better.

Alison Clark Efford lives in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, and is an associate professor of history at Marquette University. She is the author of German Immigrants, Race, and Citizenship in the Civil War Era. She has published in journals such as the Missouri Historical Review and the Journal of the Civil War Era and in several edited collections.

Alison Clark Efford lives in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, and is an associate professor of history at Marquette University. She is the author of German Immigrants, Race, and Citizenship in the Civil War Era. She has published in journals such as the Missouri Historical Review and the Journal of the Civil War Era and in several edited collections.

Viktorija Bilić, who received her doctorate from Heidelberg University, is an associate professor of translation and interpreting studies at the University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee. She is the author of Historische amerikanische und deutsche Briefsammlungen: Alltagstexte als Gegenstand des Kooperativen Übersetzens and numerous articles.

Viktorija Bilić, who received her doctorate from Heidelberg University, is an associate professor of translation and interpreting studies at the University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee. She is the author of Historische amerikanische und deutsche Briefsammlungen: Alltagstexte als Gegenstand des Kooperativen Übersetzens and numerous articles.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com