Dominic Janes

In Freak to Chic: ‘Gay’ Men in and out of Fashion after Oscar Wilde, a unique intervention in the study of queer culture, Dominic Janes highlights that, under the gaze of social conservatism, ‘gay’ life was hiding in plain sight. Indeed, he argues that the worlds of glamour, fashion, art and countercultural style provided rich opportunities for the construction of queer spectacle in London. Inspired by the legacies of Oscar Wilde, interwar and later 20th-century men such as Cecil Beaton expressed transgressive desires in forms inspired by those labelled ‘freaks’ and, thereby, made major contributions to the histories of art, design, fashion, sexuality, and celebrity. NOTCHES is grateful to Bloomsbury for granting permission to reprint this edited extract.

“The old believe everything; the middle-aged suspect everything;

the young know everything.”

Wilde, “Phrases and Philosophies.”[i]

Grand public events at which the guests wore masks and costumes had been popular in many parts of Europe since the later Middle Ages. The practice was particularly associated with carnivals in Venice and became widespread in England in the eighteenth century. Events open to the general public were held at indoor venues but also in pleasure gardens such as those at Vauxhall in south London. The use of masks enabled prominent individuals to mingle incognito. Amusing confusions of identity were encouraged: commoners might ape the aristocracy and pallid Britons assume the guise of swarthy Turks. These events were often attended by women, and perhaps also men, who were interested in selling their sexual services. For such reasons the morally reformist Victorians reinvented these events to fit their evolving notions of respectability. Masks were often abandoned, and more stress was placed on “fancy dress” costumes that represented particular historical characters. Rising incomes meant that the middle classes were able to participate in such entertainments, either in public venues or at people’s private homes, but costumed parties still retained a degree of association with upper-class privilege.

The “fancy” in “fancy dress” referred less to finery than to the notion that you were dressing according to your whim. Victorian fancy dress balls differed from the masquerades of the eighteenth century in that they sometimes had an emphasis on self-revelation. A woman of progressive opinions might, therefore, choose an exaggerated form of rational dress. This enabled her to make a point about her own beliefs and yet to suggest that she found humor in their more extreme expression. Fancy clothing was also expected to reveal rather than conceal class position, and the thought of the working classes dressed in the costumes of famous aristocrats from history duly provoked mirth in Punch. There were social limits on what was acceptable and the fancy dress ball at this time was typically not about sexual experimentation. While such attitudes had not vanished by the interwar period, some people were using fancy dress in a way that pushed the boundaries of revelation in gender and sexuality, as when Virginia Woolf, to take one example, assumed the character of Sappho. Cross-dressing, which had long been used in single-sex schools in theater performances, became a prominent feature of the more daring fancy dress events organized by young people. Understanding how this happened involves looking at the lives and attitudes of a group of people who were referred to in the media as the “bright young things” or “bright young people.”

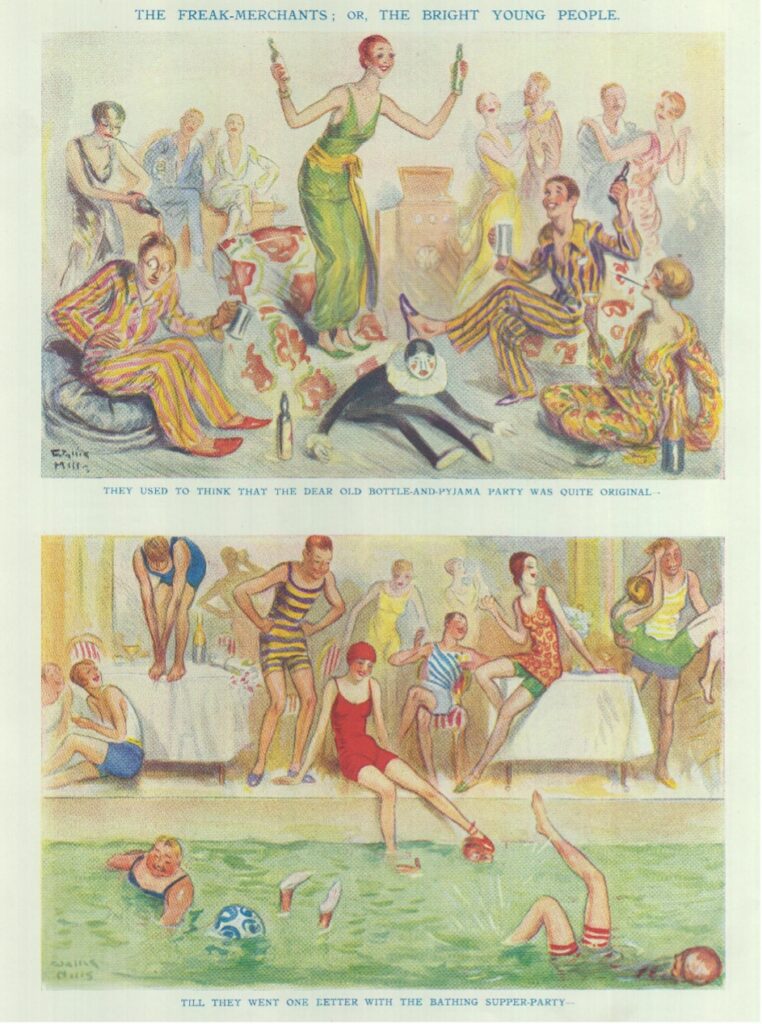

Many of the members of this set were queer, and some of them, such as the photographer Cecil Beaton, were to play an important role in making outré styles chic. This was not the same as the construction of a proudly homosexual identity, since the resulting cultural work employed the concept of “freakery” as a luxurious eccentricity. It was, however, radical in so far as it was conceptually derived from the phenomenon of freak shows of marginalized individuals such as bearded ladies that often accompanied circuses. Freakishly innovative fancy dress was not inspired by earnest theorizing, nor by reading pamphlets by Edward Carpenter on “the intermediate sex.”[ii] This had the result that homoeroticism, when it did emerge as an implication of certain freak performances, remained marginal and socially problematic. In 1930 Punch published a pair of cartoons titled “The Freak-Merchants” (fig. 1), which showed a group of young people who had developed a fad for swimming parties in their frivolous search for new sensations.[iii] By this date, the antics of a relatively small but highly visible and well-connected group of socialites had been making the headlines for several years. Masquerade parties had been wildly popular since the eighteenth century, but the association with freakishness as an aspect of society high jinks was new. In the society magazine The Sketch, the columnist “Mariegold” reported in 1920 that “freak parties” were enjoying a vogue among the younger set.[iv] A circle of London-based individuals competed to host events where innovation was key, no matter how bizarre, or indeed queer, the results. In retrospect, it was all too easy to dismiss the phenomenon as a mere expression of social decadence, especially as the high point seems to have been reached in the months just prior to the Wall Street Crash, which began at the end of October 1929. After that, there was less money available for partying and a considerably less indulgent public mood toward the foibles and eccentricities of the economically and socially privileged few.

Queer men were prominent as both guests and hosts of freak parties. What was widely acclaimed as one of the last major freak events, the Red and White party, was hosted on November 21, 1931, by the rich American Arthur Jeffress (who was a patron and partner to the artist Francis Bacon’s friend the photographer John Deakin). Two years earlier, an entertainment given by the aesthetes Stephen Tennant and Brian Howard had been saluted in a headline in The Sketch as a “Greek ‘freak party’: the great urban Dionysia.”[v] In June of the same year, the critic Robert Byron, who was also queer, was providing readers with commentary on “freak parties” in the pages of Vogue (illustrated by Cecil Beaton).[vi] It is important to stress that the personal styles on display at such events were often deliberately at odds with normative constructions of gender and sexuality, involving, as they characteristically did, elements of burlesque, anachronism, and cross-dressing. This was, in other words, partying that should be taken as seriously by cultural critics as it was by the traditionalists and moralists who condemned it and who were delighted when it fell out of fashion.

So, who were the “bright young things,” and what did that term imply? The cartoons in Lewis Baumer’s Bright Young Things: A Book of Drawings (London: Methuen, 1928) are full of stereotypes of fast young men, ditzy “flappers” and manly young women. Their image in the interwar media has had a huge influence on the way in which they are understood today. A representative view of this social group appears in D. J. Taylor’s Bright Young People (London: Vintage, 2008). He adopts something of a moralizing tone toward them as snobbish youngsters who did little more than become famous for being famous. They were few and they were metropolitan. They were, however, as Taylor admits, hugely influential as a result of the media attention that they attracted. A core of individuals who knew each other well thus came to influence a generation. And many of them were ‘gay’ in both the earlier sense of ‘happy’ as well as in the later sense of the word:

Homosexuality was as characteristic of the Bright Young People as a cloche hat or an outsize party invitation. No English youth movement, it is safe to say, has ever contained such a high proportion of homosexuals or—in an age when these activities were still illegal—been so indulgent of their behaviour.[vii]

There are several reasons why this set has not been seen as central to queer history in Britain. The left-wing slant of much lesbian and gay liberation has produced a literature that tends—often with good reason—to be wary of social elitism and critical of past failures to establish an agenda for law reform. In racial terms they were pale, if hardly stale. However, much cultural change has been shaped by queer members of the social elite whose creativity, even if often closeted, should not simply be dismissed. Furthermore, in comparison with mainstream attitudes of their time, they were progressive on issues of social mobility. Upstarts, so long as they were ‘amusing’, were welcomed. They focused neither on identity politics nor on establishing neat categorizations of homosexual versus heterosexual. This does not always make them easy to analyze, or indeed to like. For example, what is one to make of Evelyn Waugh? He bullied “sissies” when at school and parodied them in his bright-young-things novel Vile Bodies (1930). He became a husband and a father, yet same-sex desire formed the emotional core of Brideshead Revisited (1945), a novel in which he looked back with nostalgia at the lives of the aristocratic elite during the interwar years. And what are we to make of the public reception of the group? It is no easy task to judge precisely who knew what about whom. The People was probably not far wrong in July 1927 when it declared that an event attended by Stephen Tennant dressed as the Queen of Sheba and by the bisexual actress Tallulah Bankhead as a male tennis star was “one of the queerest of all the ‘freak’ parties ever given in London.”[viii] But was the writer using the term “queer” to mean homosexual? And if so, was that how most contemporary readers would have interpreted it? Perhaps not.

In the light of such challenges, it is tempting to set the boundary of proof high and to assert that unless there is clear testimony to the contrary, what we are seeing here is not directly an expression of same-sex desire. However, the way in which these people and their parties were interpreted was regularly suffused with suspicions of sexual nonconformity. Whether or not they self-identified as “homosexual,” it is quite clear that many of the men and women involved in the inner or outer circles of the bright young things were well aware of the unorthodox nature of their own sexual desires. This can be seen from letters, diaries, and privately circulated texts such as Lord Berners’s fantastically camp story The Girls of Radcliff [sic] Hall. This literary confection was supposedly written in a frenzied few hours at some point in the mid-1930s. The “girls” in question are in fact a set of queer men, most of whom had been bright and young a few years earlier. A number of significant people are known to have possessed a copy, including the writers and critics Clive Bell, Cyril Connolly, Michael Sadleir, and Carl Van Vechten. Connolly’s copy is annotated with a list that identifies the main characters:

Lizzie Johnson, Peter Watson

Millie Roberts, Robert Heber-Percy

Miss Carfax, Lord Berners

Olive Mason, Oliver Messel

Madame Yoshiwara, Pavel Tchelitchew

Daisy Montgomery, David Herbert

Cecily Seymour, Cecil Beaton.

The relationship between Robert Heber-Percy, who was to be Lord Berners’s heir, and Peter Watson, with whom Cecil Beaton was infatuated, appears thus: “Millie was growing into a very pretty girl. She had latterly become less of a tom-boy and given up perpetually playing her silly pranks. She developed a decided talent for ‘chic’ and really looked very smart. Lizzie was proud of being seen about with her and was delighted at being able to show her off to her girlfriends as ‘her latest conquest.’”[ix]

Counterfactual history is often used to explore a range of alternative political trajectories, but it could also be put to social and cultural uses such as to speculate as to what might have happened had Oscar Wilde not lost his libel case in 1895. He might very well have avoided prison and a pauper’s death in Paris in 1900. Had he lived, he would have been sixty in 1914 and could well have attended the freak parties of the 1920s as a bright old thing.

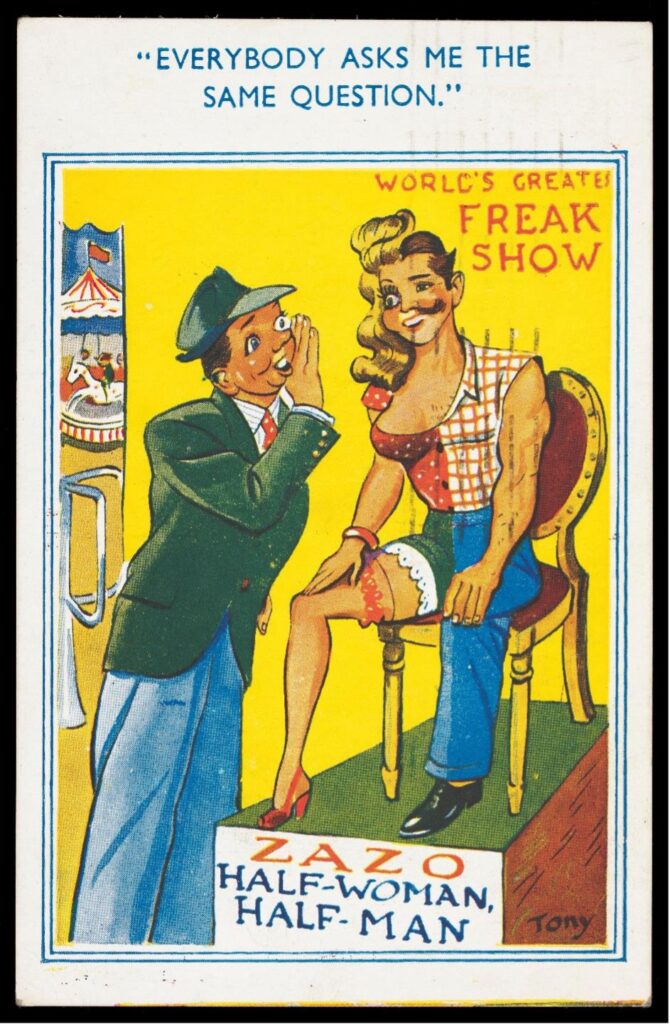

What happened, in reality, was that the stylishness of freaking was a transient cultural phenomenon and ostentatious play with gender ambiguity came increasingly to be mocked. The old style of freak shows continued, particularly in seaside resorts, to entertain the British with extremes of height, girth, hirsuteness and mutation. The bawdiness of the seaside postcard was firmly heterosexual and presented queer men, when they were noticed at all, as bizarre spectacles. This can be seen from a postcard by “Tony” which implicitly compared a young homosexual man with a “half-woman half-man” on display at the “World’s Greatest Freak Show” (fig. 2).[x] By the mid-century freak was no longer chic and the fact that it had ever been so had been conveniently forgotten.

Dominic Janes is Professor of Modern History at Keele University, UK. He is a cultural historian whose specialism is the study of texts and visual images relating to Britain in its local and international contexts since the eighteenth century. He also teaches and researches on the wider histories of gender, sexuality and religion and is Professorial Fellow in the School of Fine Art and Photography, University for the Creative Arts, UK. His latest book is Freak to Chic: ‘Gay’ Men in and Out of Fashion after Oscar Wilde (Bloomsbury, 2021).

Dominic Janes is Professor of Modern History at Keele University, UK. He is a cultural historian whose specialism is the study of texts and visual images relating to Britain in its local and international contexts since the eighteenth century. He also teaches and researches on the wider histories of gender, sexuality and religion and is Professorial Fellow in the School of Fine Art and Photography, University for the Creative Arts, UK. His latest book is Freak to Chic: ‘Gay’ Men in and Out of Fashion after Oscar Wilde (Bloomsbury, 2021).

[i] Oscar Wilde, “Phrases and Philosophies for the Use of the Young,” in Wilde, Epigrams; Phrases and Philosophies of the Use of the Young (London: Keller, 1907), 139–45, at 144.

[ii] Edward Carpenter, The Intermediate Sex: A Study of Some Transitional Types of Men and Women (London: George Allen and Unwin: 1912).

[iii] Arthur Wallis Mills, “The Freak Merchants; or, the Bright Young People,” Punch 178, Almanack (1930), unpaginated.

[iv] “Mariegold,” “Mariegold in Society,” Sketch, March 13, 1920, 482.

[v] Anon., “Society’s Greek ‘Freak Party’: The Great Urban Dionysia,” Sketch, April 17, 1929, 126.

[vi] Robert Byron, “The Perfect Party’” Vogue 73, no. 12 (June 12, 1929): 43–45 and 86.

[vii] Taylor, Bright Young People, 203.

[viii] Quoted and discussed in Alison Oram, Her Husband Was a Woman! Women’s Gender-Crossing in Modern British Popular Culture. London: Routledge, 2007, 80.

[ix] Gerald Berners, The Girls of Radcliff Hall, ed. John Byrne (London: Montcalm and the Cygnet Press, 2000), vii, 69 and 95–96.

[x] “Tony,” “‘Everybody Asks Me the Same Question’” (London: E. Marks, c.1953).

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com