Moderated by Judy Tzu-Chun Wu

In December 2021, Alexander Street/ProQuest is launching Queer Pasts, a new digital history platform that will present topical exhibits featuring historical essays and primary sources. Modelled on Women and Social Movements (WASM), currently edited by Judy Tzu-Chun Wu (University of California, Irvine) and Rebecca Jo Plant (University of California, San Diego), Queer Pasts will be available primarily via college and university institutional subscriptions. This roundtable, moderated by Wu, features the coeditors of Queer Pasts, Lisa Arellano (Mills College) and Marc Stein (San Francisco State University), along with two of the project’s early contributors, Laura Fugikawa (Colby College) and Pablo Mitchell (Oberlin College).

What are your goals for Queer Pasts?

Lisa Arellano: We are centrally committed to expanding the field of queer history. As we build this database, we are prioritizing projects that focus on the experiences and perspectives of under-represented historical groups, including people of color and trans people. We’d like to emphasize that Queer Pasts uses the term “queer” in its broadest and most inclusive sense, embracing lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender topics as well as other sexual and gender formations that might be seen as queer today but weren’t necessarily seen as LGBT in the past. In our exhibits, the term “queer” comes into play for non-normative genders and sexualities; for same-sex and cross-gender desires and acts that existed before the rise of LGBT identities and communities; and for more recent forms of gender and sexual transgression that might not call themselves LGBT.

Marc Stein: We also love the idea of presenting peer-reviewed historical essays alongside related primary sources. Each exhibit—and we’re deliberately using that term to evoke the idea of a museum exhibit—will feature an introductory essay by a historian and 20-40 primary sources used by that historian in their work. In a typical journal article or scholarly monograph, the primary sources are hidden from view and not easily accessible; in Queer Pasts, the primary sources will be there for readers to explore and examine.

Lisa Arellano: We are lucky to have WASM as a model; the primary source exhibits in the collection are extensive and enormously useful. In fact, WASM has some exhibits with queer content. Judy, do you want to talk a bit about those exhibits?

Judy Wu: I’m enormously proud of the first primary source document that Rebecca Jo Plant and I published, an oral history collection of trans folks in the Midwest. Created and curated by Jamie Wagman, “Transgender in the Heartland” (https://alexanderstreet.com/products/women-and-social-movements-united-states-1600-2000) features 20 oral histories with transgender women and men who grew up or live in the Midwest, many in small towns and rural areas. Having recently taught at Ohio State University, I recognize the places and contexts that the storytellers share, as they seek to find community in a fairly conservative part of the country.

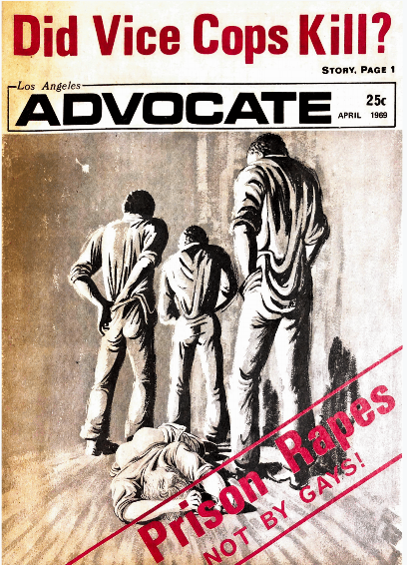

Lisa Arellano: Marc and I hope to find ways to cross index content like this in the future. Our launch in December includes three projects that, we hope, demonstrate our ambitions for the Queer Past database. Pablo Mitchell’s exhibit, “Reclamation Projects: An Archive of Queer Latinidad, 1800-1920,” incorporates a diverse array of sources about queer life in “rooming houses and boarding schools, dance halls and brothels, big city streets and mining camps.” His introductory essay does a great job asking readers to think expansively about what constitutes the “queer latinx past.” Marc’s project, “Power, Politics, and Race in the 1968 Philadelphia Study of Prison Sexual Violence,” focuses centrally on an influential government report on prison sexual violence and includes a diverse array of contemporary journalistic sources. Read together (and analyzed in Marc’s introductory essay), the project enables readers to think carefully about the challenges of using government documents and media sources to do queer history (and in particular African American queer history, trans history, and carceral history).

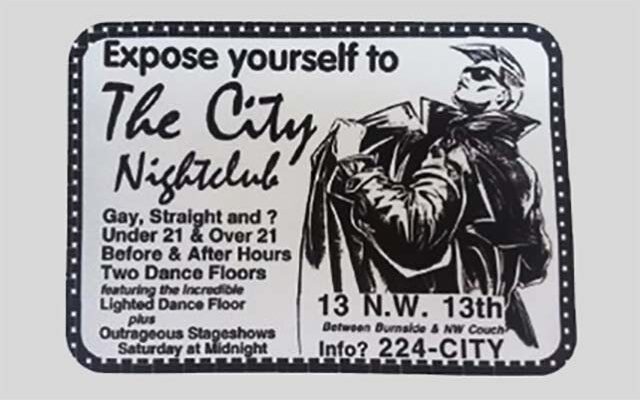

Marc Stein: Lisa’s exhibit, “The City Nightclub: A Community of Queer Youth in Portland, Oregon, 1977-1997,” focuses on an all-ages LGBT nightclub that flourished in the 1980s in Portland, Oregon. Her work helps readers revisit and think critically about some of the fundamental concepts and categories that we use in studying queer history, including youth, age, desire, and consent. We’re also excited about the projects that are planned for the spring, including Laura Fugikawa’s, which is titled “Are There Really Only Two Asian Lesbians in Chicago?”: Queer Asian Visibility and Community Formation in Chicago, 1980s-1990s.”

Lisa Arellano: I was familiar with Laura’s archival work in Chicago from our time together at Colby. When Marc and I began to work on Queer Pasts, I knew I wanted to invite Laura to be one of the first contributors. In Laura’s work, we can see some of the exciting ways that archive formation and historical research are connected.

How did each of you select your topics?

Laura Fugikawa: When I taught in Chicago, my students were unable to locate local histories or primary documents about queer Asians. This inspired me and my colleague (and community member) Liz Thomson to co-create the Queer Asian American Archives (QAAA) at the University of Illinois, Chicago (UIC). Our purpose is to work with community members to collect queer Asian material and oral histories for future historians. With the exception of Gay Asian and Pacific Islanders of Chicago (GAPIC) newsletters from the 1990s, most of the QAAA collection chronicles events after 2000. I saw this exhibit as an exciting opportunity to share material about queer Asian life in the Midwest during the 1980s and 1990s and begin to contextualize the material collected in QAAA.

Pablo Mitchell: When I first started this project, I was a little worried that I might not have enough archival material to focus on a particular period in Latina/o history like the nineteenth century, so I was thinking about a pretty broad time frame, even stretching up to the 1980s or so. Lisa and Marc encouraged me to focus on an earlier period, which I really appreciated. It led me to choose the years 1850 to 1920 or so. I also really wanted it to be Latina/o-focused, not just look at one or two groups, so I worked hard to find a range of sources from Chicana/os and Puerto Ricans as well as Cubans and Central Americans and even a Spaniard.

Lisa Arellano: Marc and I really appreciated Pablo’s willingness to shift the period of his exhibit. As we build the first few rounds of exhibits, we’ve worked hard to create a kind of overall balance of region, population, period, and topic. In the first round, Marc and I both did exhibits that focus on the post-1960 period. For example, I chose my topic because I spent many happy nights at The City Nightclub as a young person and have realized, in retrospect, how remarkable the venue and its proprietor (Lanny Swerdlow) were (and are). Like many queer historical projects, this one is deeply personal. As I did the research, the complexities around youth, consent, and policing developed.

Marc Stein: My project also grew out of my personal history, but more in the sense of my personal intellectual history. In my dissertation (1994) and first book on Philadelphia (2000), I included a few paragraphs about the city’s groundbreaking 1968 study of sexual violence, but I have long wanted to do more with this remarkable source, which Regina Kunzel also highlighted in Criminal Intimacy (2008). I have occasionally revisited the research for conference papers, but Queer Pasts finally gave me the opportunity to re-examine the sources, complete follow-up research, and situate my work in relation to the growing scholarship in carceral studies.

What’s your favorite primary source in your exhibit?

Lisa Arellano: Without a doubt, the door sign from The City nightclub—it says (among other things) “no overt heterosexual behavior” (all in capital letters). I remember loving this sign as a teenager and I knew I wanted to include it in the exhibit.

Marc Stein: In my case, it’s so hard to choose! I’m fascinated by Michael Selber’s 1969 article in The Los Angeles Advocate about prison sex and prison sexual violence, primarily because he wrote as an ex-prisoner who was gay. I’m also glad I got to include short homophile newsletter articles by two Philadelphia lesbians whom I interviewed thirty years ago. And there are several mainstream media articles that allow us to think about what it might have been like to be a trans woman who was sexually violated in prison and then publicly humiliated in court.

Pablo Mitchell: I really like the sources on boarding schools and colleges like the ones from the all-boys Peugnot School in New York City and the all-women St. Mary’s Academy. In some respects, the sources are thin, just the names of the students and their home countries, but they also point to the intimate, even queer, potentials of same-sex spaces. The sources, like the class list in the St. Mary’s Academy annual catalogue from 1899, also offer the fascinating possibility that many more Latinas and Latinos may have journeyed far from home to get an education than we know about it and that some of them may have formed new, intra-Latina/o intimacies in the dining halls and classrooms and dorm rooms across the US in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Laura Fugikawa: My favorite primary sources are the Chicago-based queer Asian newsletters. Each publication was a collective effort and reveals what ideas and events were important to the newsletter creators. While often different in content and style, the newsletters were a crucial way queer Asians reached out to one another locally and globally. The newsletters also were sites for self-expression, analysis of international LBGTQ news, and announcements of upcoming political events–items often not covered in US Asian and queer publications.

What was the biggest challenge you faced in producing your exhibit?

Pablo Mitchell: I think the biggest challenge was just finding the primary sources. Latina/o folks obviously engaged in all kinds of queer sexual activities and intimacies in the 19th and early 20th centuries. But actually finding documents about these experiences can be kind of hard, especially source about ordinary people who tended not to leave many written records of their lives. I’m really indebted to the terrific work other scholars have done in uncovering many of these sources and hope that this exhibit can help us find even more of these kinds of documents.

Laura Fugikawa: While there are great queer and Asian American histories about Chicago, there is little queer Asian history of Chicago and the Midwest. The experience of putting this exhibit together really highlighted the importance of oral histories to contextualize the archival material.

Marc Stein: Obtaining copyright permissions is often the greatest challenge in producing exhibits like these. As project editors, Lisa and I have really appreciated the hard work of Pablo, Laura, and our other contributors in dealing with this—it’s work that often is hidden from view and not recognized as much as it should be. For example, LGBT periodicals are generally very accommodating, but mainstream periodicals often see opportunities to make profits with licensing agreements. I was very fortunate that one of Philadelphia’s main newspapers from the 1960s, the Evening Bulletin, is no longer publishing, and I was able to persuade the Philadelphia Inquirer to let me reprint a good number of their articles without having to push too hard on the argument that publishers with long histories of anti-LGBT bias should not be making further profits on old content. Beyond that, I would say that it was challenging to access the voices of imprisoned African Americans (more than 80% of Philadelphia prisoners in the late 1960s) and imprisoned trans people (whose stories we encounter in my exhibit through the prism of biased government documents and media sources).

Lisa Arellano: I want to join Marc in acknowledging our contributors’ hard work behind the scenes. I also agree with Marc about access and voice, though my source issues were smaller in scale and more personal. In the case of The City, a number of the primary documents are in people’s personal collections. I was very lucky that Lanny Swerdlow and Gregory Franklin (who did a lot of video work at the club) were willing to help me. But there are some other sources that were not available. My exhibit focuses on the recent past; people are very invested in their own memories of what happened.

What is uniquely valuable about presenting your work on the Queer Pasts platform? How do you want readers to make use of your exhibit?

Marc Stein: I’m excited about sharing these incredible government, media, and social science sources about prison sexual violence—in scanned originals and searchable transcripts–alongside my introductory essay. I hope this will encourage other researchers—undergraduates, graduate students, faculty, and independent scholars—to follow up with the research leads I’ve provided and do more work on prison sex and prison sexual violence. For classroom teachers, I think our exhibits are easily adaptable for reading, writing, and research assignments. All of them could be used in trans, gender, sexuality, and historical methodology courses, and Lisa’s would be great for courses on the history of youth, Pablo’s for Latinx history courses, and Laura’s for Asian American and Chicago history courses. For activists and advocates, I hope my project will raise the profile of prison sexual violence as an ongoing problem and motivate people to work on the shameful history of “cruel and unusual punishment” in carceral institutions.

Lisa Arellano: I’m excited about the interdisciplinarity of our project. I do primary source research and teach courses about the past—but I come from an interdisciplinary background. A number of other early contributors come from interdisciplines and all of our exhibits invite multidisciplinary engagement. For me, as an interdisciplinary scholar, this kind of historical work is especially interesting.

Laura Fugikawa: It is my hope that the introductory essays accompanying the primary documents will provide critical background information and inspire researchers to engage with topics and themes with which they might be less familiar. This material may provide new insight into queer politics and Asian American communities in Chicago.

Pablo Mitchell: As someone who uses a lot of primary sources in my teaching, one of the things I really like about this exhibit is the chance it gives other teachers to use these primary sources. I would love it if a teacher would download, for instance, the article about Luisa Capetillo with a picture of her wearing men’s clothes and make copies and distribute it to their class and talk about it.

What topics would you like Queer Pasts to explore in the future?

Lisa Arellano: We are currently working with contributors on projects on mid-19th century black “drag” in Washington, D.C., and Baltimore; non-normative genders in rural communities in the late 1800s and early 1900s; the enforcement of sexual and gender norms in the Mexican diaspora in the United States in the early 20th century; LGBT student activism in Michigan in the 1960s and 1970s; and HIV bans on immigration in the early 1990s. In addition to these projects-in-development, we are in conversation with scholars working in a number of important topical areas—carceral queer subjectivities, lesbian and transgender border wars (and alliances), Queer Asian Pacific Islander activism in San Francisco, black lesbian social and political life in mid-twentieth century Philadelphia and New York, and black lesbian feminism. In all cases, our editorial intent remains the same—to prioritize projects that focus on the experiences and perspectives of under-represented historical groups. We are also being careful to attend to regional differences and temporal breadth, and to remain welcoming to inter- and multidisciplinary approaches to studying the past. In the not too distant future, we hope to create an open call; but the first few years will be comprised of recruited work. On that note, have you given any more thought to our invitation to do a project on Mom Chung, Judy?

Judy Wu: It’s so fun to be able to revisit the life of Margaret Chung, the first American-born Chinese female physician. She adopted masculine clothing and a male name at one point in her life. And then a publicly maternal identity as she adopted over a thousand, mostly white-male sons into her “family” during the Sino-Japanese War and World War II. Their fictive kinship embodied the inter-racial and inter-national alliance between the U.S. and China. Chung also developed romantic and erotic relationships with other women, mostly white ethnic women. Her life was featured in Unladylike 2020, and she was featured as part of an outdoor museum on LGBT History in Chicago, Illinois, sponsored by the Legacy Project, some years back. I also had a chance to write about her life during World War II more recently for a collection that Nick Syrett and Amy Sueyoshi are editing. I need to think about what primary sources I still have in my possession and which I might relocate to put together a collection.

Marc Stein: I’m thinking about doing a project on New York City sodomites in the early 1800s, in part because we think users will be very interested in earlier historical content. We also are working to identify and recruit projects on queer disability history, early lesbian history, and Native American history. Meanwhile, we’re beginning to think about whether to expand beyond U.S. history, and if we do, how we would handle primary sources in languages other than English and Spanish and whether we want to limit ourselves to North America or go global. With thirty exhibits planned for our first five years, we have important choices to make about how we want this platform to develop. We’re looking forward to seeing how people make use of the first three exhibits and what reactions people have.

Judy Wu: Thank you so much Lisa, Marc, Laura and Pablo. I love the idea of these primary source exhibits that will allow us to explore queer pasts through textual, visual, and material sources. This digital access is particularly meaningful, given the pandemic and the increasingly scarce access to research and travel funding. You’ve opened up this rich world of diverse identities and experiences to researchers, teachers, students, and community members who are eager for this knowledge.

Judy Tzu-Chun Wu is a professor of Asian American Studies at the University of California, Irvine, and the director of the Humanities Center. She authored Dr. Mom Chung of the Fair-Haired Bastards: The Life of a Wartime Celebrity (University of California Press, 2005) and Radicals on the Road: Internationalism, Orientalism, and Feminism during the Vietnam Era (Cornell University Press, 2013). Her forthcoming book, Fierce and Fearless: Patsy Takemoto Mink, First Woman of Color in Congress (New York University Press, 2022), is a collaboration with political scientist Gwendolyn Mink. Wu is currently working on a book that focuses on Asian American and Pacific Islander Women who attended the 1977 National Women’s Conference and co-editing Unequal Sisters, 5th edition, with Routledge. She is also a co-editor of Women and Social Movements in the United States, 1600-2000 (Alexander Street Press), editor of Amerasia Journal, and co-president of the Berkshire Conference of Women Historians.

Lisa Arellano, formerly an associate professor at Colby College, is a research associate in Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies at Colby and a Visiting Professor of Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies at Mills College. Her research and teaching focus on comparative social movements, critical historiography, and violence studies. Her first book, Vigilantes and Lynch Mobs: Community, Nation and Narrative, was published by Temple University Press in 2012. She is co-editor, with Amanda Frisken and Erica Ball, of the Fall 2016 issue of the Radical History Review, entitled, “Reconsidering Gender, Violence and the State.” Arellano’s current book manuscript, Disarming Imagination: Violence and the American Political Left, addresses high profile rape revenge cases, anti-violence activism, militant political movements, and dis/utopian political literature.

Lisa Arellano, formerly an associate professor at Colby College, is a research associate in Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies at Colby and a Visiting Professor of Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies at Mills College. Her research and teaching focus on comparative social movements, critical historiography, and violence studies. Her first book, Vigilantes and Lynch Mobs: Community, Nation and Narrative, was published by Temple University Press in 2012. She is co-editor, with Amanda Frisken and Erica Ball, of the Fall 2016 issue of the Radical History Review, entitled, “Reconsidering Gender, Violence and the State.” Arellano’s current book manuscript, Disarming Imagination: Violence and the American Political Left, addresses high profile rape revenge cases, anti-violence activism, militant political movements, and dis/utopian political literature.

Marc Stein is the Jamie and Phyllis Pasker Professor of History at San Francisco State University. He is the author of City of Sisterly and Brotherly Loves: Lesbian and Gay Philadelphia, 1945-1972 (University of Chicago Press, 2000); Sexual Injustice: Supreme Court Decisions from Griswold to Roe (University of North Carolina Press, 2010); Rethinking the Gay and Lesbian Movement (Routledge, 2012); and The Stonewall Riots: A Documentary History (NYU Press, 2019). He also served as editor-in-chief of the Encyclopedia of LGBT History in America (Scribners, 2003) and guest editor of “U.S. Homophile Internationalism,” a special issue of the Journal of Homosexuality (2017). His next book, Queer Public History: Essays on Scholarly Activism, will be published by the University of California Press in 2022.

Laura Sachiko Fugikawa is an assistant professor at Colby College in American Studies and Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies and a co-founder of the Queer Asian American Archives housed at the University of Illinois-Chicago. They are currently working on their book manuscript Displacements: The Cultural Politics of Relocation, an examination of the mid-twentieth century government-sponsored racial and spatial practices directed at Native and Japanese Americans.

Pablo Mitchell is Professor of History and Comparative American Studies at Oberlin College. He is the author of West of Sex: Making Mexican America, 1900-1930 (2012) and Coyote Nation: Sexuality, Race, and Conquest in Modernizing New Mexico, 1880-1920 (2005). He is also the co-editor of Beyond the Borders of the Law: Critical Legal Histories of the North American West (Kansas University Press, 2018). A paperback edition of his Latina/o History textbook, Understanding Latino History: Excavating the Past, Examining the Present, was released by ABC/CLIO in 2017.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com