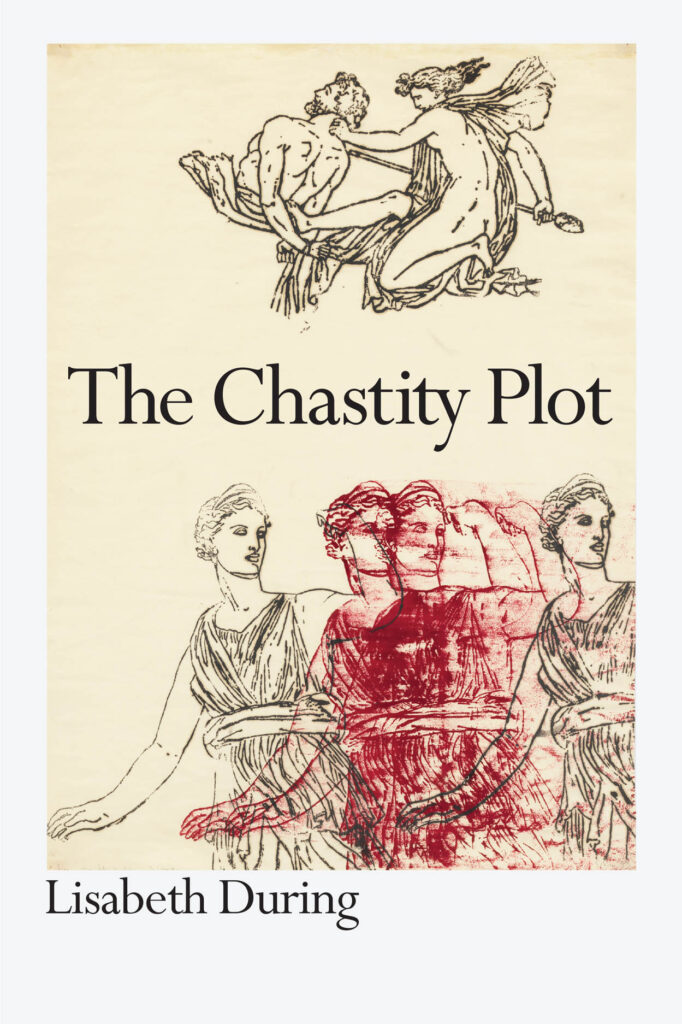

Lisabeth During

In The Chastity Plot, Lisabeth During tells the story of the rise, fall, and transformation of the ideal of chastity. An intellectually ambitious and wide-ranging book, it examines literature, religion, psychoanalysis, and cultural history from antiquity to the modern day. Instead of simply asking what chastity is, During considers what chastity can do, why we should care, and how it might influence our thinking on wider issues including sex, integrity, and freedom. In this post, she reflects on the idea of chastity, and her reasons for writing the book.

In thinking over the scope and ambitions of The Chastity Plot, a number of things come to mind. First, it is a book about the history, the fate, and the contradictions of a particular virtue, chastity. Chastity is an ideal which has been praised and recommended over many centuries. It has been promoted to many different types of communities for many different reasons. Yet its purpose and meaning are by no means clear. The more you look at it, the more chastity looks like a puzzle, the more its survival seems unlikely. That was my starting point, the desire to take seriously this strange notion, to see why – and if – it ‘matters’. (My plan was to subject it to a variety of interpretations, perhaps to attempt a genealogical reading of chastity much as Friedrich Nietzsche did for ‘ascetic ideals’ in general.)

By chastity I mean the practice of sexual restraint, and that generally includes such related ideals as virginity, modesty, continence and (often) celibacy. At its most extreme the cult of chastity calls for the total renunciation of sexual activities and even sexual feelings, a very difficult demand indeed. Modified, or domesticated, chastity refers to a practice of sexual self-control rather than utter abstinence, and here its significance is felt by women much more than by men, who have traditionally been allowed greater license, their sexual desires being considered either too urgent to restrain or too privileged to prohibit. Accordingly the code of chastity is, in the main, gendered, with the qualification that radical chastity – absolute renunciation – has been an ideal for males at least in one tradition, the Christian. Modified chastity, as history shows, does not need to preclude marriage, but it introduces into the world that dubious figure, the modest maiden and her counterpart, the fetishised virgin. These are popular, and they also are objectionable to many feminists, for good reasons. My book gives them some place but reserves its greatest interest for the figure who says no to marriage and makes a commitment to a very challenging form of asceticism, no matter how bizarre his departure from social norms may seem. (Usually, as my book shows, this figure is masculine, and adds to masculinity an interesting variation.)

The absolute renunciant, in my language, is literally or figuratively the ‘eunuch’, and the eunuch is one of history’s most curious heroes. In the eunuch’s prestige, I think you can see a rebellion against the norm of marriage, and the ubiquity of the ‘marriage plot’. If domesticated chastity, the more feminised version, encourages sweetness and submission, timidity and ignorance, the radical chastity of the eunuch is far more empowering. In the early days of chastity’s cult among the Christians of the Eastern Mediterranean, the eunuch was a star, equal in stature and glamour to the martyr. The eunuch represents a different mode of being, one untethered to society and to survival in the body: rejecting marriage, fleeing the city and its comforts for the sterility of the desert, the Christian ascetic offered a path to the condition of the disembodied angels, free from the flesh and its demands. Thus for early Christians, who expected an imminent end to the world, the eunuch was the pioneer and the virgin was the prototype of the kingdom of heaven, where there would be no marrying, no bearing of children and not even a distinction of gender. Such an ideal is unique to Christianity, even if other religious traditions also admire sexual restraint and self-denial as spiritual techniques. The ‘eunuch’s plot’ inspired me. Why had this appeared as a glittering prize in the history of religion and morals? And why does it now seem so implausible and unattractive?

We have often been told that Western culture demands repression, that it is dualistic in its privileging of mind over body, reason over the passions. If that is true (and I am not so sure it is), then the fuss about sexual virtue must be either the symptom or the cause of some of what Sigmund Freud called our cultural discontents. We have inherited a scheme of values in which saying No to our impulses and desires is generally considered a sign of maturity, even (though perhaps less so now) a mark of the ‘superior’ person, the ‘civilised’ person. I adopted Freud’s suspicion of the civilising process, his association of the bias against sex with the prevalence of ‘neurosis’. We conspire, Freud argued, against ourselves, against our own happiness. We have made ourselves strangers to our drives and pleasures. But why did this happen, and what reasons were given? Freud assumes the deed was done; I want to ask after its rationale. Why ever was the absence of sex considered a good thing, something to which morally ambitious persons would aspire? Why was refraining from sex understood as an advantage, a sacrifice someone might consider if they wanted to be ‘perfect’, if they found the ordinary achievements of life just too easy or unstrenuous? Why, for instance, did the Christian Church opt for a celibate clergy and restrict the membership of its spiritual elite to those who shunned sensuality and proved themselves immune to carnal appetites? As we know, that choice was responsible for some very unwelcome outcomes, not only a disgraceful and criminal abuse of the young and the vulnerable but also an ambivalence towards the flesh and a sense of pollution or shame infecting the whole range of human erotic possibilities. If chastity is indeed the toxin many critics of Christian morality think it is, it is hard to see why anyone would take the time to examine it as closely as I proposed to do.

I found that many people thought it was easy to identify the motives behind the chastity ideal. Yet the thinking here did not satisfy me, even while I recognised the feminist significance of a critique of female chastity. Encouraging women to be chaste, modest, virginal and even sexless, denouncing them if they were not, was something men were inclined to do, in an economy anxious to protect the ‘purity’ of the family line. A faithful and discreet wife was a highly valued possession; marrying a maiden who came blushing and ignorant to the marital bed was reassuring to the male ego. Praising chastity came naturally to those patriarchal traditions which promoted a double standard and relied on the subordination of women. When Virginia Woolf proposes chastity as a ‘profoundly interesting subject’ for a female scholar, she has this history in mind, and her ‘interest’ is an ironic one. Accepting the norm of chastity, she says to women in her ‘A Room of One’s Own’, is fatal to the woman who seeks freedom and creativity, to the women who demands an education and expects to fight for her own independence. A woman who is worried about chastity will not trust her own desires; she will expect to be protected and coddled; she will confine her sphere of operations to the home and private life. But there is another ‘chastity’, Woolf continues, which has a different meaning. Chastity can also signify autonomy, integrity, the choice of a life removed from familial bonds and, in particular, released from the duties of sexual and social reproduction. Chastity in that sense is a privilege, not a restriction, even if it does involve a measure of sacrifice or, at least, ascetic discipline.

From my research I did come to agree that Christianity was the greatest single influence in chastity’s history, the prime shaper of the power and prominence of this ideal. Earlier theories of the ideal moral life, such as those formulated by the Stoic philosophers and other Greco-Roman thinkers, also argued that sexual moderation was indispensable. But they did not view sexual desire as an enemy, as something demonic. Indeed, the patronage of Aphrodite was too important to ancient religion: defying her, as the eunuch does, could only lead to trouble. And for other cultures which flourished in the time of Christianity, the effort to dispense with marriage would have seemed insane, hardly an ideal to promote. Marriage was too important to the survival of society, too crucial to the formation of social networks and institutions, not to speak of its role in increasing or safeguarding wealth. So the Christian call for a life free of sex and marriage was profoundly odd.

As I see it, present evangelical Christians, who believe themselves to be protecting sexual virtue and purity, have seriously misunderstood the curious unworldliness of the Christian message of renunciation. Their motives are not to abolish marriage but to strengthen it by means of an ideology with some rather disturbing features. While the radical chastity of early Christianity – rejected of course by the Reformers – could be seen at times as suspending gender hierarchy and opening a spiritual/cultural space for women religious, the new chastity is adamant that gender hierarchy must stay in place. In reaction against feminism, but also against the sexual revolution and the acceptance of a much more varied sexual and gender horizon, the evangelical chastity campaign argues for the traditional double standard, expecting that women will have weaker sexual drives and are therefore responsible for the maintenance of a moral code their male counterparts do not have to obey. This state of affairs is one I find disagreeable, and if that is what people today think of when they hear the word chastity, it is no wonder that its reputation is poor.

I do see the present moment as a time when sexual ethics are significantly on the agenda: toxic masculinity, harassment, crudity, and violence are more and more threatening, and our ways of controlling them seem quite inadequate. I doubt that chastity will become the message of the sexual ethics and politics we need, but it is certainly worth reconsidering some of the values it has been associated with throughout history. Queen Elizabeth I found it a key to her enjoyment of sovereignty and independence; feminists of the late 19th century were attracted to the celibate life, and both artists and athletes, thinkers and soldiers, have at times turned away from erotic complications for the sake of their concentration, or perhaps of their soul. My case for chastity is meant to be ironic, but it does have a serious side.

Lisabeth During is associate professor of philosophy and aesthetics at Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, New York. Her new book, The Chastity Plot, was published by The University of Chicago Press in April 2021. The book is the first part of a larger project on ‘The Miseries of Heterosexuality’, and her forthcoming publications include ‘She Did it in Her Sleep: Comatose Rape and the Problem of Knowledge’ and ‘Is Impotence Funny?’

Lisabeth During is associate professor of philosophy and aesthetics at Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, New York. Her new book, The Chastity Plot, was published by The University of Chicago Press in April 2021. The book is the first part of a larger project on ‘The Miseries of Heterosexuality’, and her forthcoming publications include ‘She Did it in Her Sleep: Comatose Rape and the Problem of Knowledge’ and ‘Is Impotence Funny?’

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com