When Lietbert, bishop of Cambrai died in 1076, he had lived a long and full life. Bishop for twenty-five years, he had travelled on pilgrimage to Jerusalem, founded the Abbey of the Holy Speulchre, and suffered persecution at the hands of Robert I, count of Flanders. Lietbert was also renowned for his piety, and in particular his sexual continence. He was allegedly so keen to remain chaste that he refused to touch his genitals even when urinating, in case he accidentally became sexually aroused.

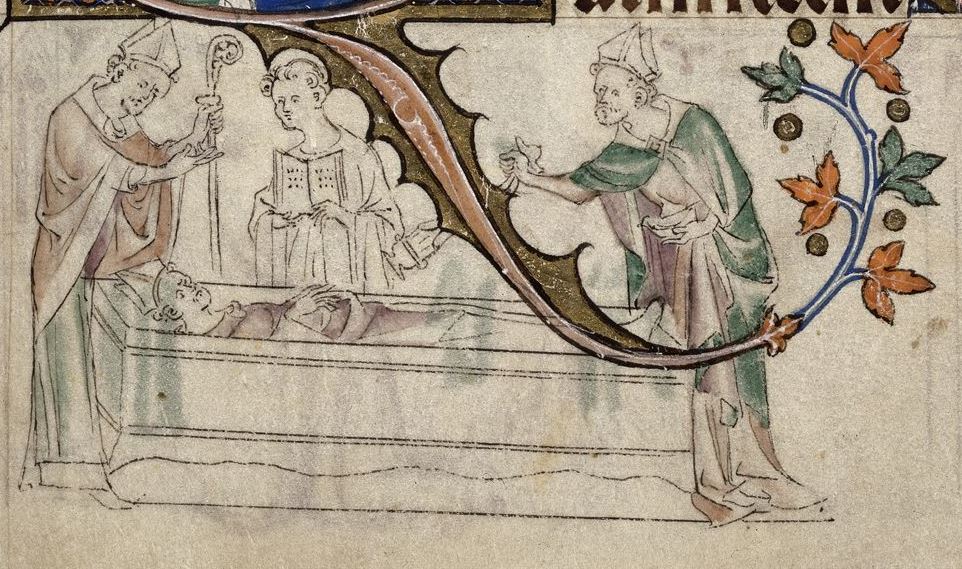

It was, however, only after Lietbert’s death that his reputation for celibacy was properly confirmed, by means of a miracle. When the bishop’s corpse was being washed for burial, his hands moved and placed themselves over his genitals. Only when the washing was completed, and the bishop’s lower body suitable covered, did his hands fall back to his sides. According to Lietbert’s biographer, the miracle provided proof that the bishop had maintained his sexual purity, and remained a virgin for his entire life.

Episcopal hagiographies were full of details which were intended to prove that the bishop had lived his life in a state of virginity, but the ultimate proof of his sexual purity could only be obtained after his death. Lietbert’s moving corpse is a particular striking example of this, but more passive bodies could also provide evidence of virginity. The condition of a corpse was believed to reflect the individual’s conduct during his lifetime: rapid decay was indicative of sin, whereas bodily incorruption (especially when accompanied by the appearance of vast quantities of balsam) was thought to reflect sexual purity.

Consequently, several hagiographies contain lengthy descriptions of the physical appearance of the bishop’s corpse. In the case of high-status individuals such as bishops, it was usual for at least a week to elapse between death and burial, and during this time the corpse was often put on display. For example, when Hugh, bishop of Lincoln died in London in 1200, his body was carried to his cathedral city and then lay in state in Lincoln Cathedral. After such a journey, a normal corpse would be beginning to decay, but Hugh’s body was remarkable for its perfection: it remained remarkably clean and lifelike, ‘clearer than glass, whiter than milk…and redder than the rose.’ Similarly, the corpse of St Wulfstan of Worcester ‘shone bright like a gem, and was white with a remarkable purity’, whilst Richard Wyche of Chichester’s body ‘shone with such a brilliant whiteness’ that it was like ‘a white lily.’

Translation (the movement of a corpse from its original burial place to a more substantial, shrine-like tomb) offered the chance to have another look at the saint’s remains, which would hopefully have remained undecayed. For example, the popular cult of Remigius of Lincoln (1067-92) was bolstered by the discovery that his corpse remained incorrupt 32 years after his death. The corpse of Archbishop Theobald of Canterbury (1139-61) was similarly perfect when his tomb was opened in 1180, causing some to hail him as a saint.

The most striking description of a virgin-bishop’s corpse relates to Edmund of Abingdon, archbishop of Canterbury, who died in 1240. Seven years later (shortly after his canonisation), his body was moved to a new shrine. Richard Wyche was present at the translation of St Edmund, and recalled the perfection and sweet smell of the corpse: ‘The entire body, particularly the face, was found unharmed and looked as if it was suffused with oil. We interpreted this as a favour merited by the intact virginity he promised and afterwards kept when he espoused the statue of the Blessed Virgin with a ring.’ Edmund’s exemplary life suggested that he was a true virgin, but his perfect corpse provided the definitive proof.

It is a well-known fact that the medieval church had a keen interest in the sexual behaviour of its members, and especially of its saints. The frequency with which perfect corpses are found in the biographies of medieval bishops reflects a lesser-known preoccupation with male virginity- a phenomenon which has received very little attention from medieval historians. The historiographical focus on female sexual purity should not blind us to the vital importance of virginity for medieval clergymen, not least in demonstrating that an individual was a perfect man, a perfect priest- and potentially a perfect saint.

Katherine Harvey is Wellcome Trust Research Fellow at Birkbeck College, University of London, where here research focuses on the pre-Reformation English episcopate. Her first book, Episcopal Appointments in England, c. 1214- c. 1344, was published by Ashgate in January 2014, and she has also written several articles on the medieval episcopal body. Her current research project is ‘Medicine and the Bishop in England, c. 1100- c. 1500.’ She tweets from @keharvey2013

Katherine Harvey is Wellcome Trust Research Fellow at Birkbeck College, University of London, where here research focuses on the pre-Reformation English episcopate. Her first book, Episcopal Appointments in England, c. 1214- c. 1344, was published by Ashgate in January 2014, and she has also written several articles on the medieval episcopal body. Her current research project is ‘Medicine and the Bishop in England, c. 1100- c. 1500.’ She tweets from @keharvey2013

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com