In 2003, California Governor Gray Davis apologized for the eugenic sterilization of over 20,000 people in the state between 1909 and 1964. Under California’s “Asexualization Law,” superintendents of state hospitals and state homes could choose to sterilize inmates diagnosed as “feeble-minded,” those deemed to have inherited mental disease, and “those suffering from perversion or marked departures from normal mentality or from disease of a syphilitic nature.” The California legislature’s apology explained that the state had been empowered to sterilize anyone with “virtually any human shortcoming or illness,” and that the state disproportionately targeted specific racial groups, including Mexican Americans and African Americans.

The historical category of “mentally defective” doesn’t map neatly onto how we might define “disabled” today. An analysis of the medical and legal discourse surrounding the practice of sterilization in California in the early twentieth century reveals that the categories of sexual deviance and disability were so interrelated that they were almost indistinct. Under the law, institutional physicians subjected girls and women to sterilization including those who were institutionalized in state psychiatric facilities (state hospitals), those in facilities for the “feeble-minded” (state homes), and those diagnosed as “mentally defective.” The category of “mentally defective” included people who today might be labeled mentally or developmentally disabled, as having learning difficulties, mentally ill, physically disabled, as well as those who would likely fit into the range of “normal.”

When applied to women and girls, different criteria identified someone as “mentally defective,” namely, sexual behavior that deviated from narrow gender ideals. Deviant sexual behavior included masturbation; same-sex sex, called “semi-sexualism”; sex outside of heterosexual marriage; incest; and being a victim of non-consensual incest or rape. Eugenicist commentators and institutional practitioners made no distinction between girls and women who were victims of sexualized violence and girls and women who engaged in forms of consensual sex. Eugenicists constituted both as “sex offenders” who could reasonably be targeted for institutionalization and sterilization. Deviant behavior also included sex inside heterosexual marriage that could produce “defective” children; therefore, any sex by physically or mentally differently abled women and girls could be considered deviant.

Two surveys of sterilization conducted in 1925 and 1937 by California eugenicists E.S. Gosney and Paul Popenoe illustrate key aspects of the discourse about mentally defective girls and women. The Human Betterment Foundation (HBF) privately funded these studies of 6,255 and 11,484 cases of sterilization, respectively. The results of the first study were published in scientific journals prior to being put into book form by HBF in 1929. The second study, which largely repeats the claims of the first, was self-published by the Human Betterment Foundation in 1938. Institutional superintendents and oversight boards shared the ideological views of Gosney and Popenoe, as evidenced by Gosney and Popenoe’s claim that “state authorities co-operated unreservedly in this undertaking,” including giving the researchers unrestricted access to patient files at state hospitals and state homes. Institutional superintendents and oversight boards made their own reflections on the necessity of mass sterilization, and the effects on patients, in annual reports to the California State legislature. These state agents made similar claims to Gosney and Popenoe, and often relied on eugenicist social science to back up their assertions. Gosney and Popenoe’s studies stand out because they were comprehensive across multiple years and institutions.

Diagnosing a girl or a woman as “mentally defective” became a means of legally containing her sexuality by allowing the state–often at the urging of parents or guardians–to institutionalize and sterilize them. Gosney and Popenoe described “for sterilization only” girls as “predominantly young women, unmarried though often illegitimate mothers, sexually delinquent and often mentally abnormal.” Their 1937 study similarly asserted that girls are “committed largely because of their promiscuity.”

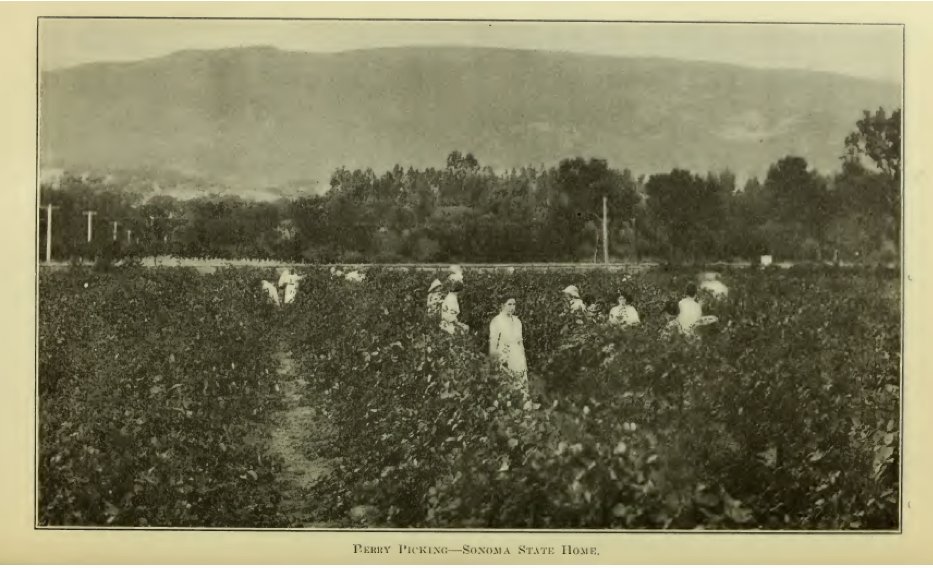

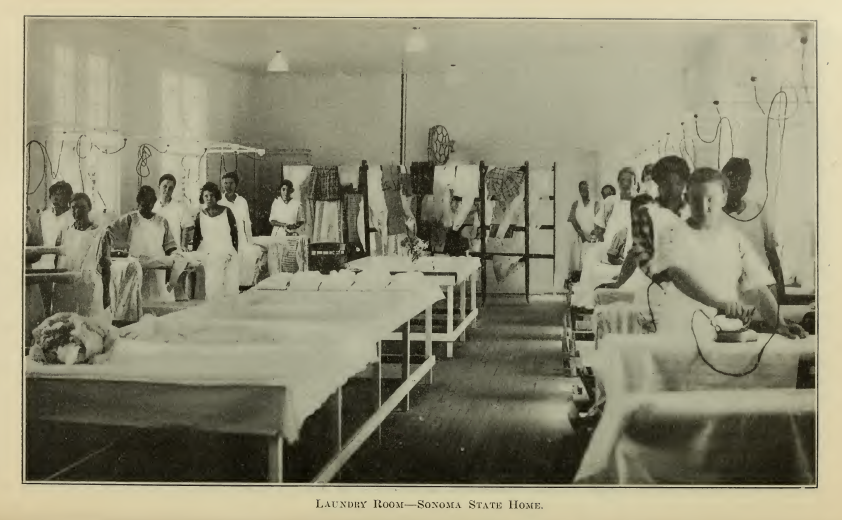

Under the very terms of the state’s Asexualization Law, sterilization was essential to the process of girls and women “making good” and being eligible for release from institutions. Once diagnosed and committed, institutions expected “mentally defective” women and girls to “make good” in order to be released on parole. “Making good,” according to Gosney and Popenoe, entailed girls and women being “disciplined and taught the habits of neatness and industry, from whence they may be returned to the community as self-supporting.” Gosney and Popenoe further defined “disciplined” as being “inhibited” and mobilizing “foresight, self-control, and judgment” in relation to alcohol and to sex.

While they argued that sterilization would protect society from girls’ and women’s “undesirable, probably illegitimate, children,” Gosney and Popenoe insisted it would not protect society from other effects of female extramarital sex. They noted that, “reproduction is by no means the only anti-social contribution such a girl can make.” Even non-reproductive sex acts, they believed, could harm society.

The possibilities for “making good” were limited. For mentally and physically different women, motherhood was out of the question. Gosney and Popenoe also targeted racial minorities and immigrants noting “an excess of insanity among the foreign born” and claiming that “the rate of mental disease among Negroes is high” thus “Negroes exceed their quota,” in the overall population. Gosney and Popenoe’s anxiety about women’s sexuality demonstrates that the eugenicist view of society rested on a foundation of fiercely policed ableist and racist gendered norms.

Eugenicists treated sexual violence as evidence that victims were mentally defective even as they viewed those same women as susceptible to sexual assault. Gosney and Popenoe warned that those with “the lowest level of intelligence” might be taken advantage of by men, and advised parents and guardians to sterilize their mentally defective children to prevent unwanted pregnancies. They referred to the case of a girl whose parents thought she was so physically “deformed” that no man would want her, yet she was “raped by a delivery man and gave birth to a child, whereupon she was sent to Sonoma to be sterilized.” This paragraph reminds us of the fact that girls, especially disabled girls, have been at high risk for sexual violence. However, Gosney and Popenoe stuck to their notion that “mentally deficient” girls were “oversexed.” They implied that girls labeled mentally defective were at least partially responsible for the sexual violence they faced, including any extramarital pregnancy that resulted from an attack. Gosney and Popenoe offered institutionalization, sterilization, and on-going state supervision through parole as solutions to sexualized violence.

Eugenicists thus forced girls and women who were medically and legally diagnosed as mentally defective to bear not only interpersonal sexualized violence, but also the reproductive violence of the eugenic state. Through discursive slippages between descriptions of sexual deviance, sexual violence, and disability, and through the medical practices legally justified by these discourses, the diagnosis of mental defectiveness legitimated the state’s reproductive control of sexually promiscuous and sexually violated girls and women in eugenics era California.

The apology for the sterilizations from the California legislature recognized, by pointing to “virtually any shortcoming or illness,” that the category of disability applied by the early twentieth century Asexualization law does not match our current conceptions of disability. Yet a close discourse analysis suggests there were consistent patterns of who eugenicists and institutional practitioners targeted for sterilization. The importance of illuminating these historical conflations of sexuality and disability is political: it provides support for political solidarity, on issues like reproductive justice, across entrenched identity categories.

Jess Whatcott is a PhD candidate in the department of Politics at University of California Santa Cruz, with emphases in Feminist Studies and Critical Race and Ethnic Studies. Their dissertation research examines how institutionalization intervened on the sexual deviance of women and girls in early twentieth century California. In a previous life, they taught at Humboldt State University, primarily in the Critical Race, Gender, and Sexuality Studies department, and organized with the prison abolition and prisoner solidarity organization Bar None.

Jess Whatcott is a PhD candidate in the department of Politics at University of California Santa Cruz, with emphases in Feminist Studies and Critical Race and Ethnic Studies. Their dissertation research examines how institutionalization intervened on the sexual deviance of women and girls in early twentieth century California. In a previous life, they taught at Humboldt State University, primarily in the Critical Race, Gender, and Sexuality Studies department, and organized with the prison abolition and prisoner solidarity organization Bar None.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com