Tatiana Ivleva and Rob Collins

Un-Roman Sex explores how gender and sex were perceived and represented outside the Mediterranean core of the Roman Empire, focusing on gender constructs and sexual behaviours in the provinces and frontier regions. Drawing on literary, epigraphic, and archaeological evidence, the contributors present new and emerging ideas on the subject of sex, gender, and sexuality in the Roman provinces.

NOTCHES: In a few sentences, what is your book about?

Tatiana: Together with our eight contributors, we explore sexuality and gender, and the perceptions thereof, and material embodiments of sex on the edges of the Roman Empire in the period spanning three centuries, from the late first to the late third centuries AD. The evidence presented in this volume all comes from outside of Roman Italy.

Rob: It is often forgotten the Roman Empire was a vast territorial entity that encompassed many different cultures and languages. However, most research on the topics of sexuality and gender is focused on classical antiquity, Italy and Greece, and examines sources written by a small elite class, consisting primarily of men. But what about all those different peoples that made up the Roman Empire, who had different notions of gender and gender roles, relationships and sexuality? Our book is the first attempt to search for other voices and untold stories at the grassroots level.

NOTCHES: How did you become interested in the history of sexuality and why did you decide to edit a volume on it?

Tatiana: I do not think that in my wildest dreams I would have ever imagined publishing a book exploring sex and sexuality. I consider myself a material culture specialist who studies everyday objects used by the people in the past. In my own work on Roman provinces, I became very interested in the topic of gender, primarily focusing on exploring the lives of migrant women and children that had followed their partners, servicemen and soldiers in the Roman army, through the objects they used in their daily lives and took on their journeys to various corners of the empire. But of course, gender studies are much more than study of women in the past. This, rather naive at that time, realisation drew me to explore the variability in genders and possible variety in sexual relations that may have existed in the regions I was interested in. But I could find only a few studies that questioned the traditional narratives. A chat with Rob revealed that I was not alone in my thinking that gender and sexuality in Roman provincial and frontier contexts are topics in need of research. However, embarking on this new research path was not without ups and downs, especially when you are not yet well versed in the intricacies of gender and sexuality studies but have no-one to consult as both topics are in their infancy in my discipline, neither they are widely taught. It was a rewarding experience however, more on a personal rather than academic level. I had a rather patriarchal upbringing, where I was constantly told to behave ‘like a girl’, dress ‘like a girl’, and choose a profession suitable for a girl. Growing up I have constantly asked myself what does it mean ‘be a girl’. It was a long way coming but I have finally found my answer.

Rob: Do you mean there are people that aren’t interested in the history of sexuality? Seriously though, when people think about sex and sexuality in the Roman context, undoubtedly the first image that comes to mind would be very similar to what is found in Rome, Pompeii or Herculaneum. But as an archaeologist of Roman frontiers, I have often come across sexual imagery, which also permeated the provinces. There are examples of phallic and vulvic carvings, erotic scenes, and other pseudo-sexual subjects found on objects and in various contexts throughout the Roman Empire, yet these are rarely mentioned, let alone studied. In short, despite a rich array of evidence, I was concerned that this evidence from the provinces and frontiers were not being incorporated into the latest scholarship. Coincidentally, Tatiana and I had reached our discontent at roughly the same time, and through discussion we knew we were on to something interesting!

NOTCHES: How far do the essays in this collection challenge popular perceptions of sex and sexuality in Roman provinces and frontiers? Is there one thing that you would particularly like readers (perhaps non-specialists in particular) to learn from this book?

Tatiana: The book challenges two entrenched views in Roman provincial scholarship. First, that sexually-explicit imagery is all about sex and is not worthy of a proper academic study, and second, that gender norms in provincial setting mirrored the Roman norms, operating at the centre of the Empire.

One of our sections is titled ‘Seeing (beyond) sex’ focusing on what is often considered to be explicit sexual imagery. One paper examines knife handles depicting what appear to be acrobatic sex acts involving three or more individuals. But can these actually be labelled as depicting ‘sex acts’? We believe many would, unconsciously, perceive such images as sexual and grotesque or titillating, but the paper challenges that assumption. Our general message here is what is sometimes perceived as having pornographic connotations by modern standards were not perceived as such in the Roman provinces and frontiers. This is not new for scholars of Roman sexuality, but this premise has hardly been expressed for the artefacts and carvings found outside the Mediterranean core.

The perception of ‘being a man’ and ‘being a woman’ in a provincial setting also varied. Conventional fixed understandings of what it meant to be ‘a masculine man’ and ‘a feminine woman’ in our discipline sidelined the complexities the contributors to our volume were able to detect.

Rob: I found it remarkable that it still remains unquestioned that the millions of individuals that lived hundreds, even thousands of miles away from Rome in the provinces, all of the diverse origins and perspectives, understood these notions in singular and fixed ways.

Tatiana: Our contributors reveal a steady number of examples showing multiple masculinities and femininities enacted in various ways, some sometimes under the ‘all-Roman’ umbrella, some sometimes consciously challenging the ‘Roman way’.

NOTCHES: What are the sources used in the book? Were there any particular challenges in using them?

Tatiana: Various sources were used to explore the topics, ranging from literary to epigraphic sources to objects of material culture. While each source posed opportunities and challenges of their own, it was the material culture that was the most challenging one, also because artefacts are rarely used in the analyses of past genders and sexualities.

Rob: Material culture comprises one of the biggest datasets for the past, considerably more than the handful of surviving texts. It is also found more widely across time AND space, meaning that investigating material culture allows us to understand those issues around sexuality and gender where we do not have accounts written by contemporary individuals as well as how things have changed over time. For example, the burial of a person is a complex act, performed by a living community to fulfil a range of social and ideological functions. Interrogating how a society chooses to commemorate a man or woman, including what objects may be included in the burial, or if there is a tombstone, is very revealing about social values around gender, age, and status.

But how can one explore material and visual indications of sex, as objects do not provide as direct an answer as a written piece of evidence. You must understand its context and think about the entire life history or biography of a single object – who made it, when, and for what reason? How did the object end up where it was found? How was its use changed over time (or not)?

Tatiana: By way of example, four contributors focus on phallic imagery and objects made in a form of a phallus. What we, as editors, found interesting, and surely our readers may see it in the same light, is the diversity of perspective. We encountered phalli in their flaccid and erect state; on objects which combine images of vulvas with images of phalli in both rested and excited state.

Tatiana: Yes, the list can go on. Exploring how each object, each image was perceived by individuals whose voices we cannot hear, accounting for the context it was found in, clearly presented a challenge.

Rob: For us, it was rewarding that each contributor provided a valuable perspective and insight that enriched study of phallic symbolism, rather than simply repeating the same message.

Tatiana: And the same conclusion is valid for other case-studies discussed. There is no fixed overarching bridge that drew all chapters together: multiplicity of perspectives highlighted the multivocal nature of material culture and other sources.

NOTCHES: Has working on this book changed your perspective on Roman sexuality? Did you find an answer to your question how was sex(uality) in the Roman provinces different from sex(uality) at the heart of the Empire? Did any new questions arrive?

Tatiana: Roman sexuality was our starting point in order to delve into the topic of gender, sex and sexuality in provincial and frontier settings. We did however find out that despite our attempts to create a picture of sexuality and gender devoid of ‘Roman’/ Mediterranean perceptions, we were unable to take Rome out of the equation. We can say that one way or another we did not deliver on the goal we set for ourselves. But that is OK; not all research yields positive or expected results, or provides the final say on the topic of study. While working on our book, there were glimpses of individual contrasting-to-Rome practices and preferences that could be inferred, but there were only a few. I personally think that the reason lies in the absence of studies exploring sexuality in pre-Roman times, with only a handful of works tackling Iron Age gender. It is a challenge in its own right, of course, as many of these societies did not leave explicit evidence of their perceptions on gender and sex(uality). As far as I am aware, there are no books or special issues with the title ‘Pre-Roman Sex.’

Rob: Numerous glaring holes resurfaced during research for the book and commissioning contributors. For example, well-published and readily accessible digital resources and museum collections of northwestern European countries provided the evidence for many case studies, but comparable studies from Central Europe, the Near East and Black Sea region were not possible. We would love to see other scholars take the subject forward, pushing through any stigma of a ‘shameful’ topic and study it from their respective province.

One thing that frequently arose while working on the book was reconsidering how we express and articulate complex concepts as gender and sexuality, given the diverse cultural backgrounds and ages of the contributors – you could say our cultural baggage. We were all used to communicating within expected academic norms, but sometimes the words conveyed more about acceptable expression of sex and/or gender than actually communicating meaning. It meant that we all had to articulate more clearly to reduce misunderstanding.

NOTCHES: This book is about the history and archaeology of gender, sex and sexuality, but what other themes does it speak to?

Tatiana: It speaks to various themes actually, with nearly every chapter bringing to the surface some other topics. It is impossible to cover everything, so I will focus on a few that caught my eye as an editor and contributor. The chapter on ‘sexual acts’ on knife handles devotes attention to the topic of ancient humour and spectacle. For me, it is quite an eye-opener that the image on such quotidian object might have been ‘a citation joke’ or allusion, now completely lost on us. It is like looking at a cartoon in The New Yorker but having no idea why it is funny. That the objects might have been used as props during performance of sexual act either ‘in words, gestures, nudity and narrative’ in the public arena of spectacle adds to the discussion of the nature of entertainment on the edges of the Roman world. It is not all about gladiator fights or theatrical performances. A few chapters talk about magic and the use of pseudo-sexual imagery in creating personalised spells. Mix-and-matching different objects of phallic and vulvic forms created personalised apotropaic toolkits suitable for various occasions, and this speaks volumes about the beliefs and daily habits of people in the provinces.

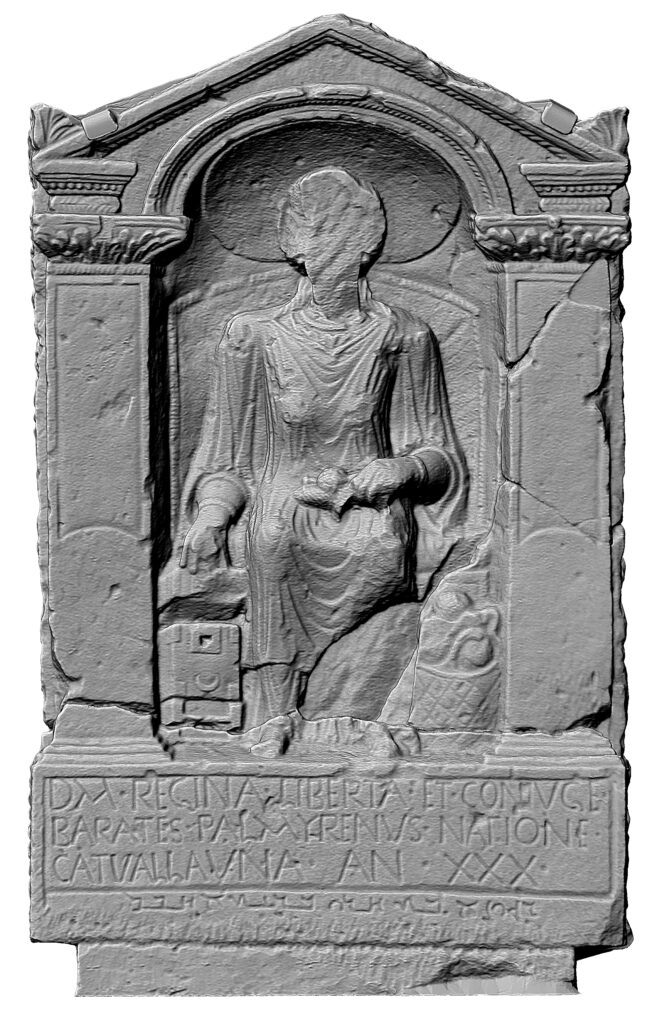

My own chapter on same-sex sexual relationships in the Roman army touches upon the topic of slavery. In trying to disentangle the nature of relationships between partners, it became obvious that unquestionably all recorded relations between master and their (former) slave, whether of same-sex or opposite-sex, are read within the framework of love and consent. Just see how the world-famous Romano-British couple Barates and Regina is interpreted as a love story between Palmyrinian merchant and a former slave girl from native British tribe. Is there a place for love in the context of a slave-owning society, I asked? To many the answer would be obvious, but for those working in Roman provincial studies, it seems to be uncomfortable and inconvenient to consider.

Rob: Humour! For me, there is always an element of ‘hehe’, because if I am honest, I have the humour of an adolescent boy. In fact, that led me to generate a typology to better categorize and analyze phallic carvings. Typology is a regular tool used by material culture specialists, and there was not one for phallic carvings, but typologies are quite often boring (… this is a type II.B.4 and so forth…). So I decided to make mine fun, and use slang to help underscore the different shapes of the carvings, like the rocket or a kinky-winky. But that combination of colloquial vulgarity and serious academic research does not sit comfortably for everyone.

NOTCHES: How do you see your book being used in the classroom, and what would you assign it with?

Tatiana: The book is suitable to appear on a variety of undergraduate and graduate syllabi. However, my dream that it will prompt the creation of a new sub-discipline and subsequent rolling course under the banner of ‘Gender and Sexuality in Roman Provinces’ within Roman archaeology.

For now, the most suitable place for the book would be in the classroom discussing classical sexualities as it represents the diversity of evidence available from the Roman Empire. It can for instance be used alongside the classic volume Roman Sex by John Clarke, because our title is a response to his, and other volumes on Ancient and Classical Sexuality, which privilege the Mediterranean perspective. One assignment could be to compare and contrast the use of vulvatic and/or phallic symbols in Rome, Athens or Sparta, Roman London and in one of the military forts of the frontier. Or analysis of how same-sex sexual relations were enacted in Rome and in the Roman army. The possibilities for comparison are endless. The book can also be used in the course on ‘Archaeology of Sexuality’ to explore the potentials and limitations of material culture in investigating the genders and sexualities in the pre- and historical periods. For instance, our contributor Stefanie Hoss used it in her class called ‘Gender in Roman Provincial Archaeology’, where several case-studies from the book were used in the discussions pertaining to practical application of the gender theory to the archaeological record.

Rob: The book is not limited to the courses on gender and sexuality however. I have used it in my class ‘Armies and Frontiers of the Roman Empire’ as a means of considering a theme – gender relations and sexuality – in a subject that often focuses on traditional martial and ‘masculine’ subjects.

Tatiana: Agreed! Modules such as ‘Art and Archaeology of the Roman Empire’ can use various chapters from the book for the discussions on Roman-period art of sex and sexuality questioning where does sexual imagery ends and pseudo-sexual one begins (using our chapter ‘Seeing (beyond) Sex’ as a reading material). Other options include modules on Archaeological Theory. I have used some of the Roman-period examples when I was invited to give a lecture in one such course asking students to consider whether an object/an artefact has a sex and/or gender, especially when it is made in a form of a phallus, a universal icon of manliness.

NOTCHES: Why does Roman and Un-Roman sexuality matter today?

Tatiana: Gender and sexuality studies show there is no ‘one-size-fits-all’ ideal. On many occasions we contested hegemonic perspectives, brought from the shadows the voices and experiences of those individuals conveniently forgotten because they did not align with the expected norm, and contextualised everyday realities in which pseudo-sexualised imagery seemed to be omnipresent. Many scholars have effectively shown that there is no uniform, rigid version of Roman sexualities, and our book extended this to the provincial context. Essentially, ancient sexuality and the study thereof teaches us to be open to ‘outside-the-box’ interpretations, leaving the comfort zone of conventional and often regressive notions. And in that regard it matters as it helps to deconstruct harmful stereotypes and encompass multiple voices.

Rob: The Roman Empire was as multicultural as contemporary societies, and it is important to appreciate and understand gender and sexual diversity in the past as much as in the present. Furthermore, understanding gender and sexuality in Roman societies helps to further humanise these distant peoples, highlighting similarities to and differences from our own cultures.

Tatiana Ivleva studies provincial corporeal culture in its various embodiments, ranging from personal dress adornments made of copper-alloy and glass to the epigraphic visibility of sexual and other relationships. Her publications include Embracing the Provinces: Society and Material Culture of the Roman Frontier Regions (2018) and papers on migration and mobility, family formations in the Roman army, and experimental archaeology. Tatiana is a Visiting Research Fellow at Newcastle University.

Tatiana Ivleva studies provincial corporeal culture in its various embodiments, ranging from personal dress adornments made of copper-alloy and glass to the epigraphic visibility of sexual and other relationships. Her publications include Embracing the Provinces: Society and Material Culture of the Roman Frontier Regions (2018) and papers on migration and mobility, family formations in the Roman army, and experimental archaeology. Tatiana is a Visiting Research Fellow at Newcastle University.

Rob Collins is a specialist of Roman frontier studies and small finds, with a particular focus on late antiquity; his research explores themes of identity, place, and regionality. His monograph, Hadrian’s Wall and the End of Empire (2012), was the first comprehensive study of a late Roman frontier. Other publications include Hadrian’s Wall 2009-2019 (2019), Roman Military Architecture on the Frontiers (2015), and Finds from the Frontier (2010). Rob is a Senior Lecturer at Newcastle University.

Rob Collins is a specialist of Roman frontier studies and small finds, with a particular focus on late antiquity; his research explores themes of identity, place, and regionality. His monograph, Hadrian’s Wall and the End of Empire (2012), was the first comprehensive study of a late Roman frontier. Other publications include Hadrian’s Wall 2009-2019 (2019), Roman Military Architecture on the Frontiers (2015), and Finds from the Frontier (2010). Rob is a Senior Lecturer at Newcastle University.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com