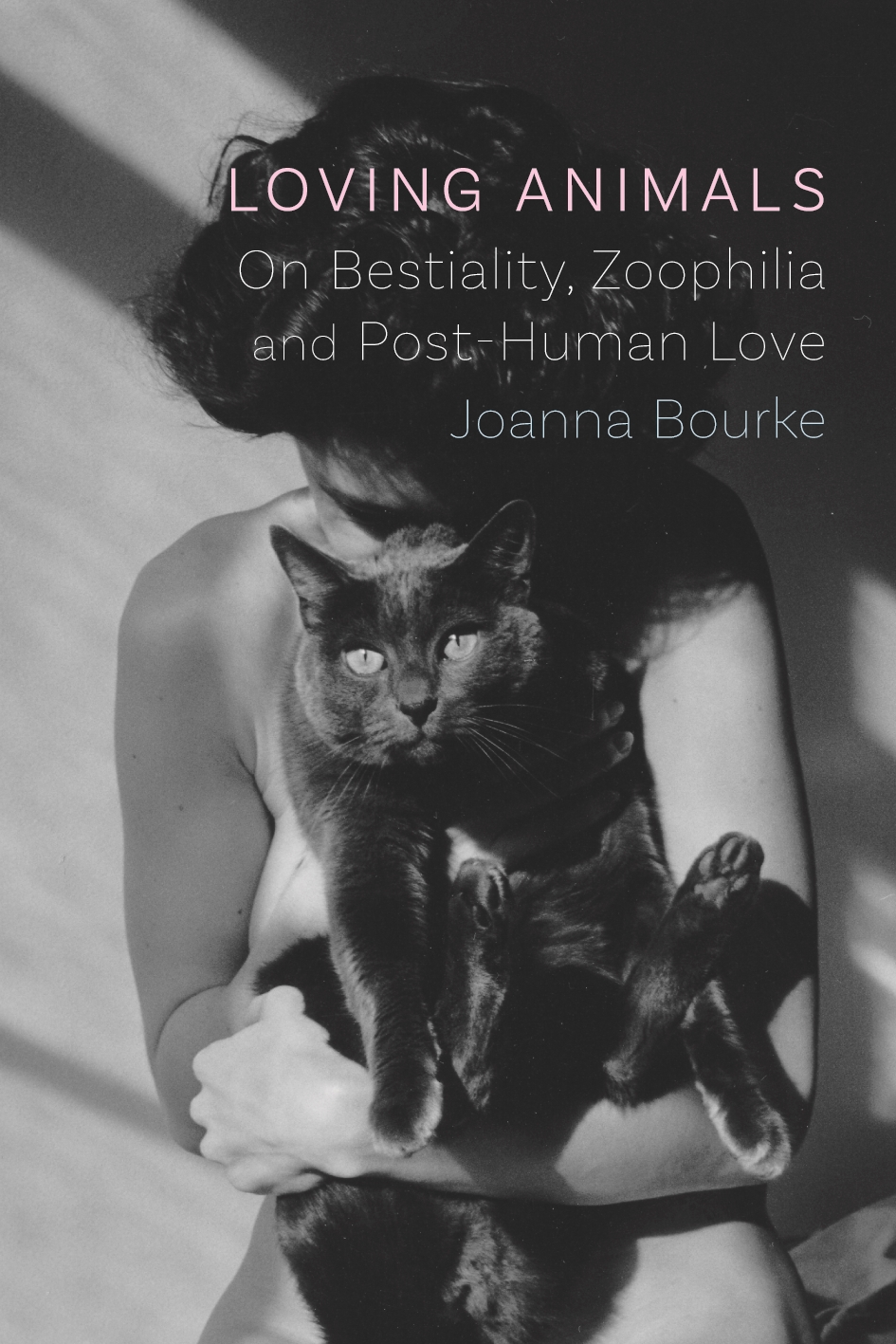

Loving Animals traces through some of the complex and sometimes tricky aspects of our relationships to companion species. This includes legal and religious views about bestiality; the sexual abuse of nonhuman and human animals; the medicalisation of interspecies sexual intercourse; culminating in the diagnosis of ‘zoophilia’ or the (sexual) love of animals. It is not enough to merely critique political and ethical positions on human-animal sexuality: people and ‘pets’ are already in dialogue. This thought-provoking book explores ways for a more equitable, fulfilling, and erotic world for everyone. NOTCHES is grateful to Reaktion Books for permission to reproduce this extract from the Introduction.

People have a poor track record in expressing love for other creatures. We admire exotic ‘wildlife’, while destroying their habitats. We are distressed by the unkind treatment of animals but regulate their slaughter within abattoirs. Western lifestyles are wholly dependent upon farming animals, which involve practices of extraordinary cruelty.

However, many of us sincerely love ‘our’ animals. We call them ‘pets’. In fact, pet ownership probably goes back to Paleolithic times. In the UK, the pet population is around 51 million; 45 percent of people ‘own’ one. Although pet owners are reluctant to allow their animals to act according to their ‘nature’ (and many even euthanize them when they become disobedient, unattractive, or old), there is general agreement that love for pets means giving them food and water, ensuring they get exercise, and talking to them. Half of all pets in the U.S. sleep in the same bed with a member of the human-family. We maintain fictive kin relationships with them. We indulge them, buy them presents, give them names, and look upon them as ‘almost human’. We kiss and caress them.

What we don’t do is ‘have sex’ with them. At least, most of us don’t. Sex with animals is one of the last taboos, the final bastion of human exceptionalism. The prohibition of what is sometimes called ‘bestiality’ distinguishes the human subject from the animal object.

Why is sex with animals such a taboo? While all other arguments about human exceptionalism have been dismantled, bestiality remains off-limits. It is only in very recent years that some people have begun to undermine the absolute prohibition on zoosexuality. Are their arguments dangerous, perverted, or simply wrongheaded? Or are we entering a new and more amorous phase in human-animal relations? And what does it mean to love nonhuman animals? More pertinently: what does it mean to love?

This book explores the modern history of human sexual encounters with other species. How have British and American commentators talked about sex with animals and what changing meanings have been attached to ‘bestiality’ or ‘zoophilia’? I am curious about debates about whether people who are sexually attracted to nonhuman animals are psychiatrically ill. Do they have a ‘paraphilia’, a psychiatric term combining the Greek prefix ‘para’ meaning ‘besides’ with ‘philia’ meaning ‘love’? Or are they just normal people who happen to have a minority sexual orientation? Given the fraught debates about consent in human-on-human sexual encounters, it is worth asking whether nonhuman animals can ever consent to libidinal relations with humans?

I am no fan of arguments based on human exceptionalism. The fundamental premise of this book is that bestiality is not an affront to the ‘dignity of man’; neither does it degrade people ‘below the level of animals’, as philosopher Immanuel Kant decreed. Kant believed that humans possess an inherent dignity, but I suggest that nonhuman animals do as well. Indeed, nonhuman animals possess inviolable rights to have their interests and preferences respected. They do not exist to serve human ends. Their lives matter to them, as do ours.

I argue that ‘queer theory’ can help us understand inter-species erotics. The concept of ‘queer’ has many meanings. It used to refer to individuals or behaviours designated ‘strange’, even ‘weird’. From the 1970s onwards, however, the concept was embraced by the gay movement to refer in positive ways to themselves. LGBTQ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer) identities celebrated their difference from heteronormativity. Queer theorists have gone even further, deconstructing and rejecting binaries such as heterosexual/homosexual, masculine/feminine, mind/body, reason/emotion, culture/nature, and human/animal. They resist the dominant culture’s accusation that queer people are ‘unnatural’, perverted, and offensive. They valourise difference. A queer theorist such as Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick laments the ‘cultural practice of sorting people into kinds’ and applauds the openness of queer definitions. ‘Queer’ cross-species love, therefore, can be seen as a further repudiation of attempts to insist on constrained sexualities. But its radical anti-essentialism also sits uneasily with the zoo’s demands for rights and their insistence on identity politics. ‘Z’ or post-human love is the most disruptive of the ‘queers’.

This is why this book embraces a post-humanist discourse that acknowledges the embodiment and embeddedness of the animal in the world. I will be suggesting that animals are actors in society. This serves to challenge the anthropocentrism of history, human exceptionalism, and the idea that ‘culture’ is an entirely human preserve. Although we can never truly ‘know’ the Other, I believe that we can make sensible deductions. This book, therefore, is a contribution to a new turn in animal studies away from rights-speak towards ‘rites’, performativity, hybridity, inter-relatedness, and queerness.

We need to emphasize not only the risks of harm to animals (which is the important contribution of animal rights scholars and others), but also their need for affection, companionship, and pleasure. Happiness is morally relevant. There are no limits to erotic creativity. We can all imagine ways of being companionate with an animal: a form of trans-species connectedness. Both human and nonhuman animals experience the world through encounters, collaborations, conflicts, and bonds of affection. As I discuss throughout this book, the main way humans interact with animals – including companion species – is violent, thoughtless, and zoocidal. But it doesn’t have to be that way. In the words of philosophers Sue Donaldson and Will Kymlicka in Zoopolis: A Political Theory of Animal Rights, the first things humans must do is ‘recognize that animals are trying to communicate’. We must then be attentive to ‘individual repertoires’, such as vocalizations and gestures, before ‘respond[ing] appropriately’. It is a dialogic, co-created exchange since the animals in our lives must know that ‘attempts to communicate with us are not a wasted effort’. As a result, interspecies relationships can be complex, rich, and fulfilling. Love – that most intimate and vulnerable emotion – is itself a ‘coup de foudre’; it is ungovernable. By being ‘open to otherness’, we might finally find ourselves edging towards becoming true companion species.

Joanna Bourke is Professor of History at Birkbeck, University of London, and a Fellow of the British Academy. She is also the Gresham Professor of Rhetoric and the Principal Investigator of a Wellcome Trust-funded project entitled “SHaME” (Sexual Harms and Medical Encounters). She is the prize-winning author of thirteen books, including Loving Animals. On Bestiality, Zoophilia, and Post-Human Love (Reaktion Books).

Joanna Bourke is Professor of History at Birkbeck, University of London, and a Fellow of the British Academy. She is also the Gresham Professor of Rhetoric and the Principal Investigator of a Wellcome Trust-funded project entitled “SHaME” (Sexual Harms and Medical Encounters). She is the prize-winning author of thirteen books, including Loving Animals. On Bestiality, Zoophilia, and Post-Human Love (Reaktion Books).

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com

1.- Animal rights: the author should mention the castration that is inflicted to every pet.

2.- I think that sex with animals may be condemned by the same reasons you don’t have sex with children: it is a question of mental maturity and capacity of the pet to decide, to be free and able to say “yes”.

This is Joanna. The person who mentioned castration is absolutely right. Also the casual sexual cruelty of “ordinary” animal husbandry (just think artificial insemination practices — “rape racks”). I devote a lot of space in the book to these comparisons. I also agree about the need to interrogate questing of consent and why sex with children is always wrong. Consent is preoccupation of the book.

You should really read the book, both of your points are discussed.