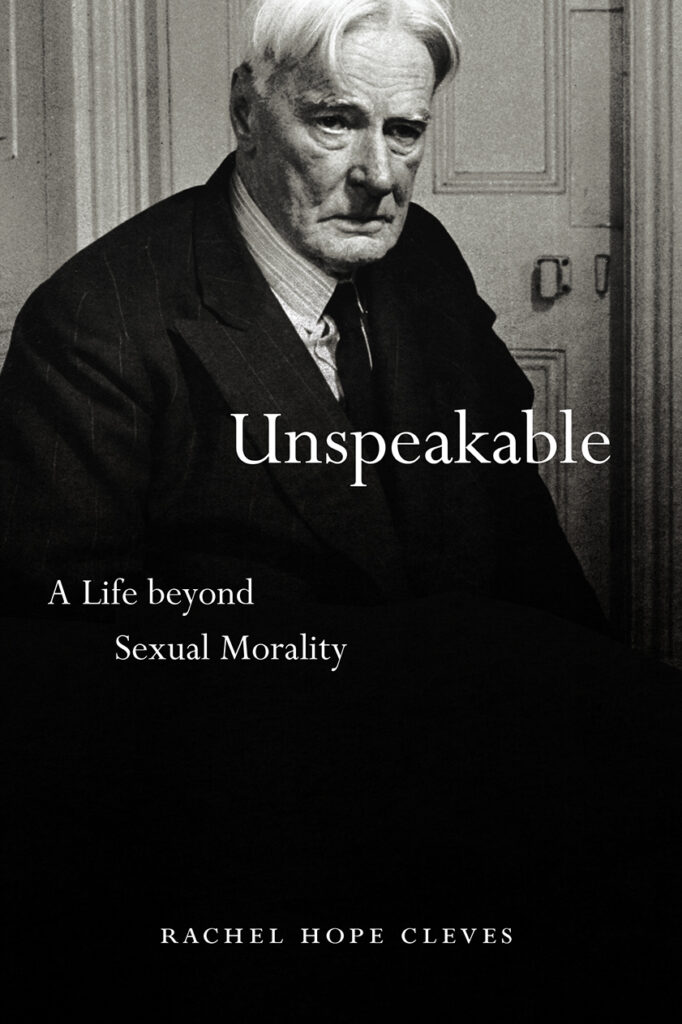

This is the second post in our online symposium on Unspeakable: A Life Beyond Sexual Morality, Rachel Hope Cleves‘s new history of intergenerational sex as revealed by the sexual activities of the once well-known British writer Norman Douglas (1868–1952). As Cleves explains in the introduction, “political disincentives,” “visceral discomfort,” “cultural taboos,” and “the limitation of sources” have long “stymied research into adult-child sex.” In Unspeakable, Cleves insists that we must push through these barriers if we are to understand contemporary sexual politics. “Pedophilia is the third rail of contemporary culture,” Cleves observes. “There is no way to understand the third rail without grabbing hold of it.”

Unspeakable: A Life Beyond Sexual Morality is a captivating book about the life of the infamous British writer Norman Douglas (1868–1952). Rather than a standard biography, as Rachel Hope Cleves explains, her latest monograph is “a history told through the story of a man” (2). Norman Douglas’s life is “a window onto the past” (12), a lens that allows us to see the “ordinariness” of a pederastic sexual system which, though alien and disturbing to many of us today, was far less scandalous in the first half of the twentieth century. Douglas’s sexuality somehow enticed friends and fans who ambiguously engaged in a behavior described by Cleves as “active non-knowing” (61). By analyzing the “wicked” (180) life of a notorious pederast, who searched for child sex in Russia, Great Britain, the Middle East and particularly in Italy, Cleves successfully demonstrates the constructedness and historicity of morality, sexuality, and childhood. The historian emphasizes that our difficulty today in imagining “the appeal of a notorious pedophile” is “a reflection of how sexual morals have shifted since the 1920s” (182).

Norman Douglas was born in a world in which German and British literati glorified neo-Hellenic pederasty and regularly visited Italy – where same-sex practices had been decriminalized in 1889 – to fulfill their erotic fantasies. Douglas, we read in the book, “was very much a man of his time” (281) who “took part in thriving markets in child sex” (281). His pederasty was not a secret to friends and readers, and he wrote freely about his erotic encounters with boys. In his books and everyday life he unashamedly advocated for the legitimacy of intergenerational sex. The British writer relentlessly pursued his sexual appetites throughout his life, and Italy was his favorite place when searching for lovers and partners.

In recounting Douglas’s life, Cleves offers an insight into a socio-cultural system that did not recognize child prostitution as a horrendous crime but rather as an activity that financially supported many poor Italian families. Unspeakable is not the first work to reveal how Northern European men felt themselves seduced by the streets of Venice, Florence, Capri, and Taormina. But Cleves moves beyond the pornographic “fantasies of virile handsome men and beautiful willing boys” (5) that constituted the stereotypical image produced by other nineteenth- and twentieth-century pederasts. By mining sources such as Pino Orioli’s diary, Cleves successfully exposes Douglas’s real-life practices.

Unspeakable pushes us to consider a world where pre-pubescent and adolescent boys – and more rarely girls – were sexually involved with older men, often with their parents’ complicity, in exchange for money and sometimes social advancement. Cleves invites scholars to ask new – and uncomfortable – questions about the history of family and childhood in liberal and Fascist Italy. Moreover, her findings compel us to analyze continuities and discontinuities in the history of sexuality, family, and youth in Italy before and after 1945. Douglas’s biography helps to bring into view a broader reconceptualization of youth, childhood, and juvenile sexuality in Italy. But it also encourages us to ask new questions about the ways in which the “economic miracle” and massive migration from South to North affected sexual attitudes and behaviors in post-Fascist Italy.

After WWII, as Cleves explains, Douglas wanted to escape his British “exile” and return to Italy at all costs. He could not stand his life in London anymore. He wanted to spend his final years having sex with boys in his favorite country. Once back to his beloved Capri he was warmly welcomed by the population. The citizens of Capri granted Douglas honorary citizenship of the island and treated him as a benefactor until his very last days. His funeral was an event, where Douglas’s coffin, followed by friends, admirers, and dozens of locals, was carried in procession through the island, giving the writer a last chance to “say farewell” to the alleys, squares, and panoramas that were the inspiration for his literary production and the backdrop to his “libertine” life. Douglas’s burial also symbolically marked the demise of the pederastic era.

Cleves’s analysis ends where my own research begins. Reading Unspeakable, reading about the sexual system in which men like Douglas operated, we can better understand why post-Fascist Italy was obsessed with the necessity of monitoring the sexuality of male children and adolescents. Exactly seven months after Douglas’s death, on September 7, 1952, the Chief of the Italian Police Giovanni D’Antoni sent a newsletter to all Prefects and police stations. This initiative had nothing to do with Douglas directly, but it was somehow related to the underworld he had inhabited for decades. In his communication entitled “Omosessualità-repressione” (Homosexuality-repression) D’Antoni explained that the recent murder of the Roman doctor Quintino Livio Caucci at the hands of two older male teens had once again drawn many Italians’ attention to “the disgusting homosexual phenomenon.” Examining Caucci’s apartment the police found, among his documents, a long list with the names of about 300 boys and young men who, as evidence suggested, had had multiple sexual encounters with the old doctor in the last two or three years. D’Antoni maintained that, even if the Italian law did not criminalize homosexuality, the police had to monitor homosexuals and keep track of their activities. The Italian police promised to fight against homosexuals, “inverts,” and pederasts, and implement measures to prevent the “corruption” of the Italian youth. In the 1950s the Italian government (led by the Catholic Christian Democrats) and the popular press carried out a wide-ranging “battaglia per la moralità” (fight for morality) to police sexual behavior, curb public indecency, and protect adolescents and children from men the campaign described as predators.

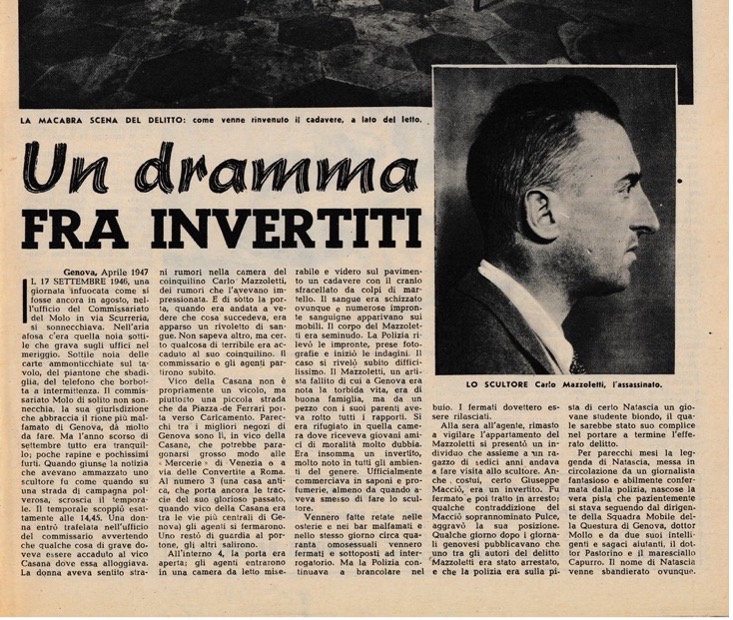

Mussolini’s regime, which forced Douglas to leave Italy in 1937, had dismantled the cronaca nera (crime news) by prohibiting the public discussion of crimes against public morality and decency. Under Fascism, newspapers were not allowed to mention pederasty, infanticide, or “vices” linked to the sexual sphere. People like Douglas and their relationships with locales were cause for concern and could not be discussed by Italian journalists. Once the regime was over, and the press was free again, newspapers and magazines enthusiastically began covering stories and topics that had been forbidden for years. Readers were particularly fascinated by crimes, and publishers knew that they could capitalize on sensationalist news filled with lurid details. Individuals and activities deemed to be of a negative moral, political, and social value, ended up holding a high commercial one. Browsing magazines and newspapers in the second half of the 1940s and in the early 1950s, Italy seemed to be rife with robberies, murders, prostitution, sexual perversion, and violence. Homosexuality, pederasty, and male prostitution were lumped together as one of the worst evils affecting the Italian population. Juvenile deviancy was presented as a dangerous social problem, and journalists asked the new state to intervene, rescue the Italian children and – with them – the future of the nation.

Journalists were not alone in underlining the “moral depravity” that had seemed to be infecting for years numerous boys and girls – particularly in the Italian South. The writer Curzio Malaparte, in his book La Pelle (The Skin, 1949), wrote of the child sex market in Naples after the end of WWII and accused foreign “inverts” of having irremediably spoiled far too many young Italian men and boys with their easy money. Media and writers, speaking the unspeakable, exposed the pederastic system to the eyes of the Italian population. The “active non-knowing” of a few, who knew about the child sex market and glossed over it, became the outraged awareness of many who asked to protect the children.

When Douglas died in the early 1950s the neo-Hellenic era seemed to be over. However, the Mediterranean kept “seducing” foreigners, and young hustlers continued to prostitute themselves. Reading Michael Davidson’s Some Boys (1970) or browsing magazines and newspapers in the 1950s and 1960s it is evident how Italian youth and children were still seeking out for long-term “benefactors” or short-term clients. But, unlike Douglas’s encounters, these ones did not seem to happen in the public eye. Acts of physical intimacy between children and adults were not displayed in the piazza anymore. Men like Douglas were no longer celebrated but rather decidedly condemned.

Writing the history of intergenerational sex is a complicated matter. It is hard to reconstruct the lived experiences of the youth and make their long-silenced voices heard. Finding instances where boys and adolescents involved in paid sex activities speak or represent themselves directly is extremely rare. We often lack precious ego-documents that would allow us to comprehend how these children and adolescents gave meaning to their experiences and interpreted their own behaviors. In my own research about male prostitution in post-Fascist Italy I am often unable to say how young prostitutes understood and talked about themselves, their activity, and their sexuality. Young prostitutes, as historical subjects, have often been silenced and their lives have remained most of the time opaque and unintelligible. Middle- and upper-class intellectuals, writers, and diarists told us who these prostitutes were, how they looked like, what they did, what they liked and what they did not like, but, most of the time, the voices of these young men remained hopelessly unheard.

Rachel Hope Cleves, by examining the letters written by Eric Wolton, René Quilicus Mari, and Emilio Papa, was able to recover the voices of some of the boys who had long-term relationships with Norman Douglas. But, similarly to the Sicilian models photographed by Wilhelm von Gloeden, the majority of Douglas’s Italian lovers – Michele, Pasqualino, Silvio, Luciano, Ettore, and many others – do not talk. By saying this I do not want to criticize a book that is incredibly successful in pushing readers to think critically about “children’s agentic sexuality” (87). However, in my opinion, we need to highlight how the “seduction of the Mediterranean” is still a literary and erotic topos for the most part narrated by foreign neo-erastai (adult males). A history of intergenerational sex recounted from the standpoint of the Italian children remains still largely untold.

Unspeakable is a scholarly gem that reminds us that historians of sexuality “cannot avoid an entire range of human behavior because it arouses feelings of disgust” (7). Rachel Hope Cleves’s book is a must read for people interested in the history of sexuality, the history of youth, the history of family, and the history of Italy. Unspeakable, in reconstructing the ways in which intergenerational sex moved from ordinary to aberrant within just a few years, reminds us that sexual mores are far less stable than we imagine, and that attitudes towards sexuality are prone to vary continuously. We cannot predict how sexual norms will change. This book warns us that, given the intrinsic fluidity of sex, sexuality, and gender, we do not know who will be the next one to be ostracized.

Alessio Ponzio is an Assistant Professor in Modern European History and History of Gender and Sexuality at the University of Saskatchewan. His first English-language monograph explored the totalitarian youth educational projects of Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany. His current book project focuses on media discourses concerning homosexuality, male prostitution, and sexual citizenship in post-Fascist Italy.

Alessio Ponzio is an Assistant Professor in Modern European History and History of Gender and Sexuality at the University of Saskatchewan. His first English-language monograph explored the totalitarian youth educational projects of Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany. His current book project focuses on media discourses concerning homosexuality, male prostitution, and sexual citizenship in post-Fascist Italy.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com