Ellen S. More

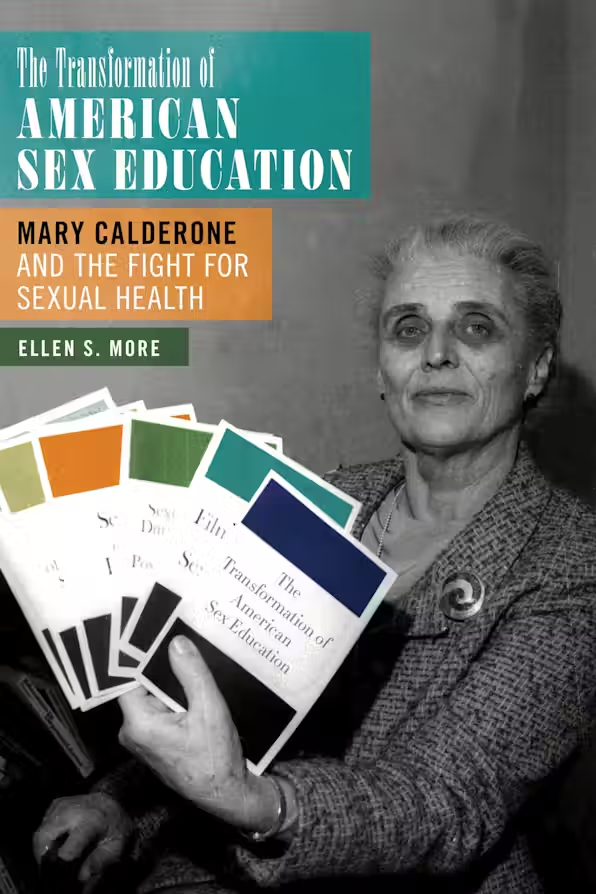

In The Transformation of American Sex Education: Mary Calderone and the Fight for Sexual Health, I tell the story of sex education in the United States from the 1950s to the present and the complicated, but central, role of Dr. Mary Calderone in its liberation from the timid approach known as “family life education.” Calderone (1904-1998), who co-founded the Sexuality Information and Education Council of the U.S. (SIECUS) in 1964, was previously the medical director of Planned Parenthood. Her commitment to eliminating the shame and embarrassment experienced by many (most?) parents, teachers, and students when talking about sexuality—something she had experienced herself—made her a powerful force for change.

Calderone’s work marked only the first phase of sex education’s transformation. Indeed, it triggered an intense reaction from newly politicized evangelical Christians and their new allies among right-wing politicians as well as personal attacks on Calderone herself. The appearance of “abstinence only sex education” and a new fearfulness based on the spread of HIV/AIDS, spurred further refinement of sex education approaches by SIECUS and other groups. Between 1989 and 1991, SIECUS leader Debra Hafner, in collaboration with others, defined the approach she titled “comprehensive sex education” (CSE). In 1991 SIECUS and two other groups published the first CSE national guidelines. My book therefore begins with Calderone herself but moves on to tell the story of the movement she set in motion, its supporters, and its encounters with right-wing religious and political opponents. Using archival resources and personal interviews, it describes the work that has been done through public schools, the Children’s Aid Society, the Unitarian Universalist Association, and the Planned Parenthood League of Massachusetts between the 1980s and the current day.

NOTCHES: Why will people want to read it? Why does it matter today?

EM: My first answer to those questions is a quotation from an opinion piece in the New York Times from 2022 by sex education researchers Eva Goldfarb and Lisa Lieberman: “After Roe, Sex Education is Even More Vital.” Today, when women—especially poor women—in the United States are facing extreme challenges to their autonomy, self-respect, and health, school-based sex education is vital to their ability to avoid unwanted pregnancies and to secure a sense of sexual competence and self-respect. Young people of all races and gender identities largely lack inclusive health education even in sex education classes. My book tells the story of the transition in the U.S. from family life education to curricula that are not marriage-centered but, rather, focused on sexual health. It also tells the history of the country’s failure to overcome well-funded, extremist campaigns to frighten parents into retreating from these gains and, indeed, to use sex education as a tool to whip up support for extremist political candidates everywhere from local school board elections to national political campaigns. My book tells a history that has not yet run its course.

It begins this story through the complex figure of Dr. Mary Steichen Calderone, whose fight to instill healthy attitudes about human sexuality arose from her own conflicted experiences as a child. Calderone was the daughter of the celebrated photographer Eduard Steichen and grew up among artists and wealthy patrons of her father. Yet by her early twenties she was floundering in an unhappy marriage with two young daughters, no money, and no sense of direction. Her ability to overcome these obstacles and become a respected (and demonized) national figure, known as the “grandmother of sex education,” is a compelling story.

NOTCHES: What drew you to this topic?

EM: In 1984, as I was beginning research for an earlier book on the history of women physicians in American medicine, I was unexpectedly asked to interview Mary Calderone. She had recently retired from SIECUS but even at 80 years of age, she was still a well-known figure. When she appeared in my office I was astonished at her vitality, theatricality, and intensity. She willingly launched into the story of her life, including tales of her famous father, and the abuse she suffered as a child when her mother bound her hands in metal enclosures to prevent her from masturbating. Calderone’s commitment to sex education was grounded in this trauma. It propelled her toward a lifelong campaign to legitimize sexuality as healthy and joyful. Although I included a few pages about her in my earlier book about women physicians, Restoring the Balance, I knew that someday I’d return to Calderone for a fuller portrait of her life and work.

NOTCHES: Did the book shift significantly from the time you first conceptualized it?

EM: Yes, absolutely. I originally envisioned this as a biography of Mary Calderone. But as time went on and I learned more about the history of sex education, it became clear that I would need to look beyond Calderone herself. Calderone’s key insights and leadership were crucial to launching a new approach to sex education, but by the time she retired in the early 1980s, 20 crucial years had passed since she began her work with SIECUS—the world had changed and the politics of sexuality with it. The redefinition of sexuality education and the way it was co-opted for political ends—those were stories that needed to be analyzed and told. Whereas Calderone cared most deeply about personal liberation and sexual joy (tempered by personal responsibility, as she always emphasized)—by the 1980s Americans were confronting the need for sex education to help young people prevent STIs (including HIV/AIDS), unwanted pregnancies, and sexual coercion. Calderone had encouraged parents to educate their pre-school-age children in an understanding of their bodies and an acceptance of childhood masturbation as a key to healthy acceptance of adult sexuality. She encouraged educators, too, to convey information about sexuality in positive ways. But by the late 1980s, even relatively progressive parents no longer felt comfortable with curricula that were sex-positive without also attending to genuine public health concerns such as AIDS, sexual bullying, and so forth. The story began with Calderone, but it did not end there.

NOTCHES: Whose stories or what topics were left out of your book and why? What would you include had you been able to? What questions do you still have?

EM: The subjects of sexual and gender identity, racial equity, and reproductive justice have steadily become more central to adequate education about sexual health. My book focuses on the years up through the early 2000s. I simply did not have time (or space) to fully address these topics. I do address them, but not nearly as deeply as I’d like.

NOTCHES: This book engages with histories of sex and sexuality, but what other themes does it speak to?

EM: Together, Calderone and SIECUS faced an unprecedented media campaign of hostility and lies from newly energized ultra-right-wing political groups in alliance with Christian evangelicals. My book examines the way sex education was turned into a flashpoint of the culture wars, a stalking horse for the newly emergent extreme right wing from the late 1960s to the present.

NOTCHES: How did you research the book?

EM: I was fortunate to be a joint fellow of the Radcliffe Institute and the Schlesinger Library for the History of Women at Harvard when I began my research on this book. The Schlesinger is the repository for the papers of both Mary Calderone and Debra Haffner, one of Calderone’s most successful successors at SIECUS. That year I concentrated on Calderone. It was a year of total immersion in her life, her work both as the medical director for Planned Parenthood and her later work as the head of SIECUS. But best of all, papers pertaining to her childhood and private life were available for me to read although they had not yet been formally accessioned and were not available for quotation. Calderone had retained for her archives highly personal documents such as a water-color she made as a child—either of her father in his flower garden or of their gardener, a 17-year-old who was discovered by her father while exposing himself to a young Mary (she could have been portraying either one). Such a document and others from her childhood provided me with evidence of experiences to which she referred many times in later life, experiences that formed the foundation of her insistence on the child’s right to experience sexual self-pleasure and the parental responsibility to avoid instilling a sense of sexual shame in one’s child. I was also fortunate to be able to interview some of the key actors in the crystallization of comprehensive sex education in the 1980s and 1990s, people like Debra Haffner, and pioneers of its deployment in the classroom such as Michael Carrera.

As I approached the end of research and writing, I learned that my own mid-sized city, Worcester, Massachusetts, was experiencing a struggle over a new sex education curriculum for the schools. Worcester’s (ultimately successful) fight for comprehensive sex education played out in much the same way as stories I’d written about from 50 years earlier—including overt lies about the program by its right-wing opponents. Many residents, however, had no idea that this was the case. Plus ça change…

Ellen S. More is a historian of the American medical profession. Her major research and teaching interests include the history of American medicine and health care with an emphasis on the history of women, the history and uses of the concept of empathy in medicine, the history and ethics of the professions, and the politics of sexuality and sex education in modern America. She is Professor Emeritus (Psychiatry) at the University of Massachusetts Medical School and author of Restoring the Balance: Women Physicians and the Profession of Medicine, 1850–1995 and co-editor of Women Physicians and the Cultures of Medicine.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com