Rebecca Davis, Gillian Frank, Bethany Moreton and Heather White

For close to a decade, the eminent U.S. historian John D’Emilio has performed an important scholarly service by urging the fields he helped establish—LGBT history and the history of sexuality—to devote more attention to religious themes and actors. In 2004, he addressed the recently founded LGBT Religious Archives Network—a group that cultivates scholarship on religion and LGBT communities— by noting an “absence of a ‘deeply researched historical study’ of LGBT movements in American religion over the past five decades.” Nearly ten years later, at the 2013 annual meeting of the Organization of American Historians, a standing-room-only crowd attested to the continued influence of D’Emilio’s and Estelle Freedman’s landmark synthesis Intimate Matters: A History of Sexuality in America. In his closing comments on this occasion of the work’s twenty-fifth anniversary, D’Emilio critiqued his own earlier work on the modern period for precisely this absence of religion and urged his audience to insist on its centrality to the field’s ongoing research agenda. At the conference, and also in the journal Frontiers, D’Emilio noted a more general absence of scholarship on the overlapping histories of religion and sexuality. But in Frontiers, and again in a 2013 article for Journal of Women’s History, D’Emilio cites just one source—Lisa McGirr’s Suburban Warriors (2001)—to signal the state of the field of religion and sexuality. He writes forcefully in the latter article:

Scholars, usefully, could turn as well to further explorations of the role of spirituality and organized religion in the sexual history of America, a subject that remains understudied despite the continuing power of religious values to shape both sexual meanings and political contests over sexuality.

Most recently, D’Emilio noted the dearth of scholarship on the histories of religion and sexuality in an Out History blog post titled “Religion is Calling.” Here, he cites the important contributions of John Howard and E. Patrick Johnson and notes the eagerly awaited work of Heather White. Yet D’Emilio also underscored that “if you browse through the index of many of the key books on LGBT history written in the last thirty-plus years [I am including my own work here], you’ll notice that religion hardly figures at all. It is barely mentioned.” Whether describing the history of sexuality in general or LGBT history in particular, D’Emilio cautions that we face a nearly empty field.

As historians deeply invested in scholarly conversations about religion and sexuality, we rejoice that such a justly influential historian as D’Emilio is encouraging others to find religion. We join wholeheartedly in his call for more scholarship on these important intersections. At the same time, we want to offer the good news that the sub-field is not as barren as these references suggest. Additional angles of vision reveal a considerably more crowded and cacophonous conversation, from graduate dissertations just taking shape to a steady supply of works by established scholars and, indeed, a vigorous set of debates underway in American pews, pulpits, and faithful public spheres. In the cherished popular tradition of the history of sexuality, which itself emerged in response to the exclusions of the academy, histories of sexuality and religion in the twentieth-century United States are in fact busting out all over as we demonstrate in a syllabus at the end of this article.

D’Emilio’s concern for the lack of religious analysis in the specific sub-field of LGBT history seems to us most accurate. As he indicates, few of the canonical works of LGBT history and few of the courses taught in that tradition have given the topic much space. Instead, certain images of disdain and bereavement dominate LGBT accounts of the religious: images of placards saying “GOD HATES FAGS,” Catholic Supreme Court justices deciding sodomy law, and haredi families sitting shiva when a gay son comes out. These are hard images to undo in the history of LGBT encounters with religious voices. Among our own students have been those expelled from their congregations in humiliation, thrown out of their mission trips, subjected to exorcisms, and publicly prayed over by their classmates for their perversity. They come to our courses on the history of religion and sexuality interested to know what other voices have to say on the topic.

This is precisely why in syllabi we work to include the many important works in LGBT history that address relationships between religion and queer experience head-on, to illustrate sexual and religious variance in the national past and to complicate the frequent conflation of religion with conservative sexual politics. Widely assigned pieces by Rebecca Davis, Gillian Frank, Kathryn Lofton, John Gustav-Wrathall, and Tim Retzloff, for example, argue that LGBT life is lived in part through religious institutions as well as in conflict with them. If we consider works in the related fields of religious studies, sociology, and anthropology, we can add such indispensable works as the ethnographic studies by Tanya Erzen and Lynne Gerber of ex-gay ministries; sociological work by Melissa Wilcox and R. Stephen Warner on the largest mass-membership LGBT organization in the world, the Metropolitan Community Church; and Moshe Shokeid’s A Gay Synagogue in New York. These works remind us that queerness has abounded in religious spaces. As the Village People thoughtfully observed, and as historians George Chauncey and John Gustav-Wrathall have documented, it was in fact fun to stay at the YMCA.

If we turn our focus to the U.S. history of sexuality more broadly, it becomes clear that there is a substantial and growing body of scholarship that takes as its starting point the intersections of religion and sexuality and insists upon them as crucial to analyzing some of the core elements of American history generally—racial formations, household formations, public spheres, economic processes, work organization, political power, ideologies and belief systems, intellectual and artistic production, migration and immigration. Certainly the historical coverage is uneven, and much work remains to be done. But scholars do not work in a vacuum; it would be surprising indeed if the capture of the nation’s formal politics by a forthrightly sexually conservative religious alliance over two generations had failed to spark an interrogation by scholars of sexuality and religion. It may be more accurate to say, as Bethany Moreton argued in a 2009 state-of-the-field survey, that much key historical scholarship on sex-saturated conservative Christianity is actually being produced in interdisciplinary departments and outlets: historians Angela Dillard, Lisa Duggan, and Barbara Savage, for example, make indispensable contributions on the uses of sexuality in American religious revival, but their scholarly production is not based strictly in history departments. Likewise, some of the best works offering historical insight on the interconnections between history and sexuality are by scholars originally trained in other disciplines entirely. Here we think of scholars with significant effect on the present interpretive landscape such as Elizabeth Bernstein, Cathy Cohen, Susan Friend Harding, Mark D. Jordan, and Linda Kintz.

This scholarship is thus developing through multiple channels. Blogs like Religion in American History, Religion Dispatches, Religion and Politics, and Notches: (re)marks on the history of sexuality have been platforms for new research on the histories of religion and sexuality. Still, it should come as no shock to historians of LGBT experiences or of sexuality more generally that established centers of history should not necessarily be our only stop in tracking the production of histories of religion and sexuality. Opportunities to connect with historical work in this vein are provided more often by interdisciplinary outlets like Columbia University’s Center for the Study of Religion and Sexuality and “States of Devotion” at NYU’s Hemispheric Institute; conferences like “Religion and Sexual Revolutions in the United States” at the Danforth Center on Religion and Politics and “Are the Gods Afraid of Black Sexuality?” at Columbia; or networks like the HRC Summer Institute for Religious and Theological Study. We, too, desire to see these topics claim their turf within the institutional apparatus of the historical discipline on par with their actual significance in the course of U.S. history, but not at the price of the interdisciplinary conversation that feeds them or the professional spaces of Ethnic Studies, American Studies, Women’s and Gender Studies, or Religious Studies which offer many of us an intellectual and ethical home.

We are also glad to be in a position to report important works in progress. In the course of collaborating on a forthcoming collection of twentieth-century U.S. histories of religion and sexuality, we have had advance exposure to works underway by scholars that include Rebecca Alpert and Jacob Staub, Eliza Young Barstow, Gregory Conerly, Gregg Drinkwater, Sara Dubow, Lynne Gerber, Elizabeth Gish, Emily Johnson, Kathi Kern, Rachel Kranson, Natalia Mehlman Petrzela, Sarah Potter, Daniel Rivers, Whitney Strub, Aiko Takeuchi-Demicri, Judith Weisenfeld, and Neil J. Young. And these are just some of the many scholars that we know are currently working on articles, books, or nearly completed dissertations on the overlapping histories of religion and sexuality in the United States across multiple confessions and time frames. Happily, the newest generation of historians is already augmenting these conversations, if dissertation proposals and grant applications are any guide. These indicators point to a field that is established, vibrant, and indeed lush, moving its focus beyond Christianity, and covering topics literally ranging from atheism to Zen Buddhism.

Moreover, these scholars can hope to address a broad readership outside the academy. Both liberal and conservative religions’ insistence on sexuality’s centrality has stoked the public appetite for analysis. Such issues as interfaith marriage, abortion, the “gay marriage” frame, the denominational splits over the ordination of “out” clergy, and the priestly sex abuse revelations demonstrate the enduring relevance of religion and sexuality to public debate; what has changed here is the degree of welcome for historically informed analyses. When the pope punts on condemning homosexuals, Masorti Jewish congregations permit same-sex ceremonies, and the Southern Baptist Convention pledges to give up the “Adam and Steve” jokes, even an academic publisher would do well to notice how many voices are raised via religious blogs and Twitter feeds.

We have been inspired by the pedagogical conversations already launched elsewhere by Monica Mercado and Carol Faulkner on teaching the histories of religion and sexuality together. In an effort to encourage the use of this work in classrooms and the engagement with it by historians of LGBT and sexuality history, we include below a sample syllabus. We debated how to organize the syllabus because the field is so robust and far-reaching, and because of how much new work is arriving on the scene that challenges disciplinary categories and insists on new interpretive frameworks. Ultimately, we decided upon a mixture of thematic and chronological units.

Rather than the last word on how to study or organize these topics, we offer this syllabus to highlight the breadth and depth of scholarship on the history of religion and sexuality and to suggest multiple means of approaching these intersections. What scholarship would you add? What scholarship is in progress that could be added in future semesters?

Sexuality and Religion

in the 20th-Century United States

This course examines the intertwined histories of religion and sexuality in the twentieth-century United States. We will investigate the transformation of religious and sexual relations in American history, and indeed of the concepts of “religion” and “sexuality” themselves. An investigation of the histories of religion and sexuality offers an opportunity to explore violent encounters, loving relationships, legal battles, political activism, commercial exchanges, class antagonism, radical and conservative activism, popular cultural representations, and intellectual debates. In exploring the intersection of these categories, we will take up other concepts as well including: race, class, gender, national identity, economy and the law.

This course examines the intertwined histories of religion and sexuality in the twentieth-century United States. We will investigate the transformation of religious and sexual relations in American history, and indeed of the concepts of “religion” and “sexuality” themselves. An investigation of the histories of religion and sexuality offers an opportunity to explore violent encounters, loving relationships, legal battles, political activism, commercial exchanges, class antagonism, radical and conservative activism, popular cultural representations, and intellectual debates. In exploring the intersection of these categories, we will take up other concepts as well including: race, class, gender, national identity, economy and the law.

Week 1: Approaches to the Histories of Religion and Sexuality

- Ann Taves, “Sexuality and American Religious History,” Retelling U.S. Religious History. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997, 27-56.

- Melissa Wilcox, “Outlaws or In-Laws? Queer Theory, LGBT Studies, and Religious Studies,” The Journal of Homosexuality 52:1/2 (2006): 73-100.

- Marie Griffith, “Sexing Religion” The Cambridge Companion to Religious Studies. New York: Cambridge University Press, 338-359.

- Linell E. Cady and Tracy Fessenden, “Gendering the Divide: Religion, the Secular and the Politics of Sexual Difference,” Religion, the Secular and the Politics of Sexual Difference. New York: Columbia University Press, 2013, 3-24.

- Bethany Moreton, “Why Is There So Much Sex in Christian Conservatism and Why Do So Few Historians Care Anything About It?” Journal of Southern History 75 (August 2009): 717-38.

Week 2: Racial Formation, Religion and Sexuality in the Early 20th Century

- Tisa Wenger, “Dance is (Not) Religion: The Struggle for Authority in Indian Affairs,” We Have a Religion: The 1920s Pueblo Indian Dance Controversy and American Religious Freedom. Charlotte: University of North Carolina Press, 2009.

- Andrew Lyons and Harriet Lyons,”The Reconstruction of ‘Primitive Sexuality’ at the Fin de Siècle,” Irregular Connections: A History of Anthropology and Sexuality. University of Nebraska Press, 2004. 100-130.

- Peggy Pascoe, “Gender Systems in Conflict: The Marriages of Mission-Educated Chinese American Women, 1874-1939,” Journal of Social History 22, no. 4 (1989): 631–652.

- Leigh Schmidt, Heaven’s Bride: The Unprintable Life of Ida C. Craddock, American Mystic, Scholar, Sexologist, Martyr, and Madwoman. New York: Basic Books, 2010.

- Val Marie Johnson, “Protection, Virtue, and the “Power to Detain”: The Moral Citizenship of Jewish Women in New York City, 1890-1920,” Journal of Urban History 31, no. 5 (July 1, 2005): 655–684.

- Sarah Gualtieri, “Marriage and Respectability in the Era of Immigration Restriction,” Between Arab and White: Race and Ethnicity in the Early Syrian American Diaspora. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009. 135-154.

Week 3: Same-Sex Intimacies

- Wallace Best, “A Woman’s Work; An Urban World,” Passionately Human, No Less Divine: Religion and Culture in Black Chicago, 1915-1952. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005, 147-180.

- John Gustav-Wrathall, Take the Young Stranger by the Hand: Same-Sex Relations and the YMCA. Chicago: University Of Chicago Press, 2000.

- George Chauncey, “Christian Brotherhood or Sexual Perversion? Homosexual Identities and the Construction of Sexual Boundaries in the World War One Era,” Journal of Social History 19, no. 2 (December 1, 1985): 189–211.

- Kathryn Lofton, “Queering Fundamentalism: John Balcom Shaw and the Sexuality of a Protestant Orthodoxy,” Journal of the History of Sexuality 17, no. 3 (2008): 439–468.

Week 4: Religion, Reproduction and Eugenics

- Christine Rosen, Preaching Eugenics: Religious Leaders and the American Eugenics Movement. New York: Oxford University Press, 2004.

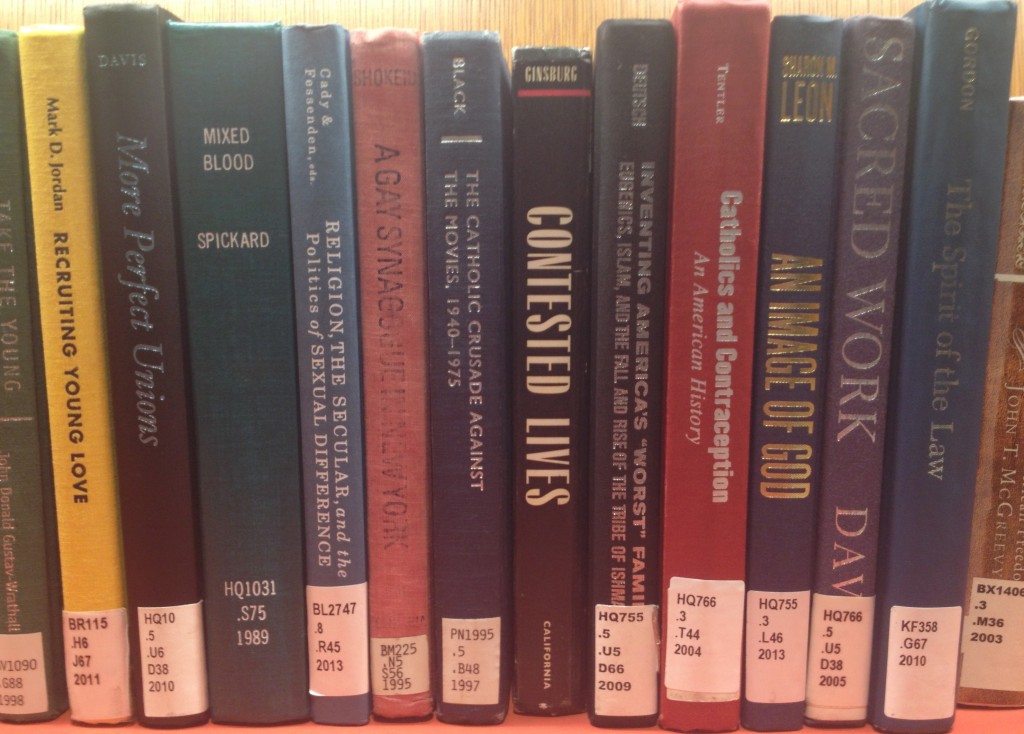

- Leslie Woodcock Tentler, Catholics and Contraception: An American History. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2004.

- Nathaniel Deutsch, Inventing America’s “Worst” Family: Eugenics, Islam, and the Fall and Rise of the Tribe of Ishmael. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009.

- Sharon Mara Leon, An Image of God: The Catholic Struggle with Eugenics. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2013.

Week 5: Holy Marriage!

- Paul R. Spickard, Mixed Blood : Intermarriage and Ethnic Identity in Twentieth-Century America. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1989.

- Rebecca L. Davis, More Perfect Unions: The American Search for Marital Bliss. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2010.

- Keren R. McGinity, Still Jewish : A History of Women and Intermarriage in America. New York: New York University Press, 2009.

- Beth S. Wenger, “Mitzvah and Medicine: Gender, Assimilation, and the Scientific Defense of ‘Family Purity,'” Jewish Social Studies 5 No. 1/2 (Autumn 1998 – Winter 1999): 177-202.

Week 6: Religion and Sexual Science

- Molly McGarry, “’The Quick, the Dead, and the Yet Unborn,’: Untimely Sexualities and Secular Hauntings,” Secularisms, Durham: Duke University, 2008. 247-279.

- Marie Griffith, “The Religious Encounters of Alfred C. Kinsey,” The Journal of American History 95, no. 2 (September 1, 2008): 349–377.

- Pamela Klassen, “Evil Spirits and the Queer Psyche in an Age of Anxiety,” Spirits of Protestantism: Medicine, Healing and Liberal Christianity. California: University of California Press, 137-168.

- Jon Roberts, “Psychoanalysis and American Christianity, 1900-1940,” When Science and Christianity Meet, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008. 225-244.

Week 7: Same-Sex Sexuality and Religion at Midcentury

- Rebecca Davis “’My Homosexuality is Getting Worse Every Day’: Norman Vincent Peale, Psychiatry, and the Liberal Protestant Response to Same-Sex Desires in Mid-Twentieth Century America,” American Christianities: A History of Dominance and Diversity, Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2011. 347-365.

- Marc Stein, “The Objectionable Walt Whitman Bridge,” in City of Sisterly and Brotherly Loves: Lesbian and Gay Philadelphia, 1945-1972. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000. 138-154.

- Tim Retzloff, “‘Seer or Queer?’ Postwar Fascination with Detroit’s Prophet Jones,” GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies 8, no. 3 (2002): 271–296.

- John Howard, “The Library, the Park, and the Pervert: Public Space and Homosexual Encounter in Post-World War II Atlanta.” Radical History Review 1995, no. 62 (March 20, 1995): 166–87.

- J. Waller, “‘A Man in a Cassock Is Wearing a Skirt’: Margaretta Bowers and the Psychoanalytic Treatment of Gay Clergy.” GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies 4, no. 1 (1998): 1–16.

- John Howard, “Politics and Beliefs,” in Men Like That: A Southern Queer History. Chicago: University Of Chicago Press, 2001. 230-256.

- Didi Herman, “Devil Discourse the Shifting Constructions of Homosexuality in “Christianity Today,” in The Antigay Agenda. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1997. 25-59.

Week 8: Religion, Sexuality and the Long Civil Rights Movement

- Jane Dailey, “Sex, Segregation, and the Sacred after Brown,” The Journal of American History 91, no. 1 (June 1, 2004): 119–144.

- Thaddeus Russell, “The Color of Discipline: Civil Rights and Black Sexuality,” American Quarterly 60, no. 1 (2008): 101–128.

- Edward E. Curtis IV, “Islamizing the Black Body: Ritual and Power in Elijah Muhammad’s Nation of Islam,” Religion and American Culture: A Journal of Interpretation 12, no. 2 (July 1, 2002): 167–196.

- E. Patrick Johnson, “Gayness and the Black Church,” Sweet Tea: Black Gay Men of the South, Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2008. 182-255.

Week 9: Sexual Revolutions and Counterrevolutions (part 1)

- Heather White, “Is Love the Only Norm? The ‘New Morality’ and the Sexual Revolution” in The Cambridge History of Religion in America: Volume III: 1945 to the Present, New York: Cambridge University Press, 2012. 224-242.

- Heather White, “Proclaiming Liberation: The Historical Roots of LGBT Religious Organizing, 1946–1976.” Nova Religio 11 (May 2008): 102–19.

- Amy DeRogatis, Saving Sex: Sexuality and Salvation in American Evangelicalism. New York: Oxford University Press, 2014.

- Neil J. Young, “’The ERA Is a Moral Issue’: The Mormon Church, LDS Women and the Defeat of the Equal Rights Amendment.” American Quarterly 59, no. 3 (2007): 623–644.

Week 10: Abortion

- Faye D. Ginsburg, Contested Lives: The Abortion Debate in an American Community. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998.

- Daniel Williams, “The GOP’s Abortion Strategy: Why Pro-Choice Republicans Became Pro-Life in the 1970s,” Journal of Policy History23 (2011): 513-539.

- Gillian Frank, “The Color of the Unborn: Anti-Abortion and Anti-Busing Politics in Michigan, 1967-1973.” Gender and History, 26, no. 2 (August 2014): 351-378.

- Sara Dubow “Defining Fetal Personhood,” Ourselves Unborn: A History of the Fetus in Modern America. London: Oxford University Press, 2010.

- John T. McGreevy, Catholicism and American Freedom: A History. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2004. 216-282.

- Tom Davis, Sacred Work: Planned Parenthood and Its Clergy Alliances. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2005.

Week 11: Adoption

- Arissa Oh, “A New Kind of Missionary Work: Christians, Christian Americans, and the Adoption of Korean GI Babies, 1955-1961,” Women’s Studies Quarterly 33, Nos. 3-4 (2005): 161-188.

- Laura Briggs, “From Refugees to Madonnas of the Cold War,” and “Gay and Lesbian Adoption in the United States,” Somebody’s Children: The Politics of Transracial and Transnational Adoption. Durham: Duke University Press, 2012. 129-159, 241-268.

Week 12: Popular Culture, Religion and Sexuality

- Gregory D. Black, The Catholic Crusade Against the Movies, 1940-1975. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1997.

- Whitney Strub, Perversion for Profit: The Politics of Pornography and the Rise of the New Right. New York: Columbia University Press, 2011.

- Gastón Espinosa, “Mexican Madonna: Selena and the Politics of Cultural Redemption,” Mexican American Religions: Spirituality, Activism, and Culture. Durham: Duke University Press, 2009. 359-380.

Week 13: Sexual Revolutions and Counterrevolutions (part 2)

- Gillian Frank, “‘The Civil Rights of Parents’: Race and Conservative Politics in Anita Bryant’s Campaign Against Gay Rights in 1970s Florida,” The Journal of the History of Sexuality, 22, no. 1 (January 2013): 126-160.

- Luis D. León, “Cesar Chavez, Christian Love, and the Myth of the (Anti-) Macho: Toward and Ethic of the Religiously Erotic,” Out of the Shadows, Into the Light: Christianity and Homosexuality. St. Louis: Chalice Press, 2009. 88-103.

- Daniel Williams, “Sex and the Evangelicals: Gender Issues, the Sexual Revolution, and Abortion in the 1960s” in American Evangelicals and the 1960s: Revisiting the “Backlash,” University of Wisconsin Press, 2014.

- Neil J. Young, “‘Worse Than Cancer and Worse Than Snakes’: Jimmy Carter’s Southern Baptist Problem and the 1980 Election.” Journal of Policy History 26, no. 4 (2014): 479–508.

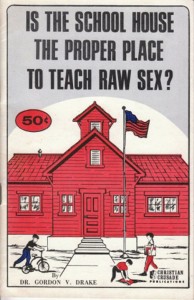

- Janice Irvine, Talk About Sex: The Battles Over Sex Education in the United States. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002.

Week 14: Sexuality, Religion and the Culture Wars

- Anthony Petro, After the Wrath of God: AIDS, Sexuality and American Religion. New York: Oxford University Press, 2015.

- Janet R. Jakobsen, Ann Pellegrini, Love the Sin: Sexual Regulation and the Limits of Religious Tolerance. New York: New York University Press, 2003.

- Laura Gutierrez, “Sexing Guadalupe in Transnational Double Crossings,” Performing Mexicanidad: Vendidas y Cabareteras on the Transnational Stage. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2010. 31-63

- Sarah Gordon, The Spirit of the Law: Religious Voices and the Constitution in Modern America. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2010.

- Sara Moslener, Virgin Nation: Sexual Purity and American Adolescence. New York: Oxford University Press, 2015.

- Andrea Smith, “‘Without Apology’: Native American and Evangelical Feminisms,” Native Americans and the Christian Right: The Gendered Politics of Unlikely Alliances. Durham: Duke University Press, 2008. 115-199.

- Angela D. Dillard, “Strange Bedfellows: Gender, Sexuality, and ‘Family Values’,” Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner Now? Multicultural Conservatism in America. New York: NYU Press, 2002. 137-170.

- Doris Buss and Didi Herman, Globalizing Family Values: The Christian Right in Global Politics. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2003.

Rebecca Davis is an Associate Professor of History and Women’s Studies at the University of Delaware. A scholar of marriage, sexuality, and religion in American culture, Davis is the author of More Perfect Unions: The American Search for Marital Bliss. Her article, “’My Homosexuality Is Getting Worse Every Day‘: Norman Vincent Peale, Psychiatry, and the Liberal Protestant Response to Same-Sex Desires in Mid-Twentieth-Century America,” received the 2011-2012 LGBT Religious History Award from the LGBT Religious Archives Network.

Gillian Frank is a Visiting Fellow at Center for the Study of Religion and a Lecturer in the Department of Religion at Princeton University. He is also a contributing editor of Notches: Remarks on the History of Sexuality. Frank has published articles on the intersections of sexuality, race, childhood and religion in the twentieth-century United States. He is currently revising a book manuscript titled Save Our Children: Sexual Politics and Cultural Conservatism in the United States, 1965-1990, which is under contract with University of Pennsylvania Press.

Bethany Moreton is a Kingdon Fellow at the University of Wisconsin and an Associate Professor of History and Women’s Studies at the University of Georgia. Her first book, To Serve God and Wal-Mart: The Making of Christian Free Enterprise won the Frederick Jackson Turner Prize for best first book in U.S. history and the John Hope Franklin Award for the best book in American Studies. Moreton co-founded Freedom University for undocumented students banned from Georgia public higher education. She is currently at work on a book about Opus Dei and post-industrial work and on Jesus Saves: Christians in the Age of Debt.

Heather R. White is a Research Scholar and Adjunct Assistant Professor at the New College of Florida, where she teaches courses in religious studies and gender studies. She was also, most recently, a Coolidge Fellow at Auburn Theological Seminary and a Burke Scholar in Residence at the theological library of Columbia University. Heather researches and writes about religion and sexuality in twentieth-century United States. Her book, Reforming Sodom: Protestants and the Rise of Gay Rights, is forthcoming from University of North Carolina Press in fall 2015.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com

Pingback: Sunday Morning Medicine | Nursing Clio

Pingback: In the News: #blacklivesmatter, #Illridewithyou, TL;DR Bible Stories & more! | The Revealer