A few weeks after the outbreak of the First World War, German lieutenant Kurt K. began a correspondence with his fiancée, Lotte, that would last through almost four years of combat. After enduring artillery bombardments for endless days and witnessing the death of his closest friend, he wrote to his fiancée: “It’s like I live more in a dream than in reality.” In his intimate expression of these feelings, Kurt K. let down his guard to confess that he may no longer be able to maintain his masculine, iron image of emotional self-control:

I feel so completely alone. The last of my friends went to East Prussia, because he had to take care of his step mother. But his brother was killed. Don’t think I’m soft. But think about it this way: if suddenly all your female friends, with whom you had shared joy and pain, were killed off, wouldn’t you also have such thoughts?

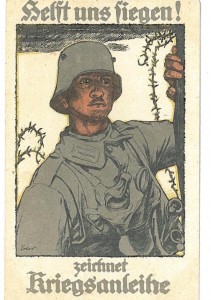

Such a willingness to expose his vulnerability, and to express his fear that Lotte would think he was ‘soft,’ marked a decisive moment for Kurt K., who wrestled with the pressures of a masculine ideal to which men were expected to conform in 1914. The dominant masculine ideal stressed emotional self-control, abstinence, and toughness. The image of the steel-nerved front soldier became ubiquitous in popular media. It was a cornerstone of postwar myths of the rugged ‘New Man’ who emerged out of the horrors of war. Further, effeminate behavior and homosexual men were denounced as threats to this militarized ideal of masculinity. During the war, however, front soldiers would modify masculine ideals to reflect their experiences with modern warfare. The officially-sanctioned ideal of an emotionally controlled, sexually abstinent warrior seemed increasingly condescending and inhumane to men who had to deal with the hardship of the front, where men sought sexual outlets and expressed emotions such as fear, anxiety, and love more openly as the war broke down inhibitions and traditional social structures.

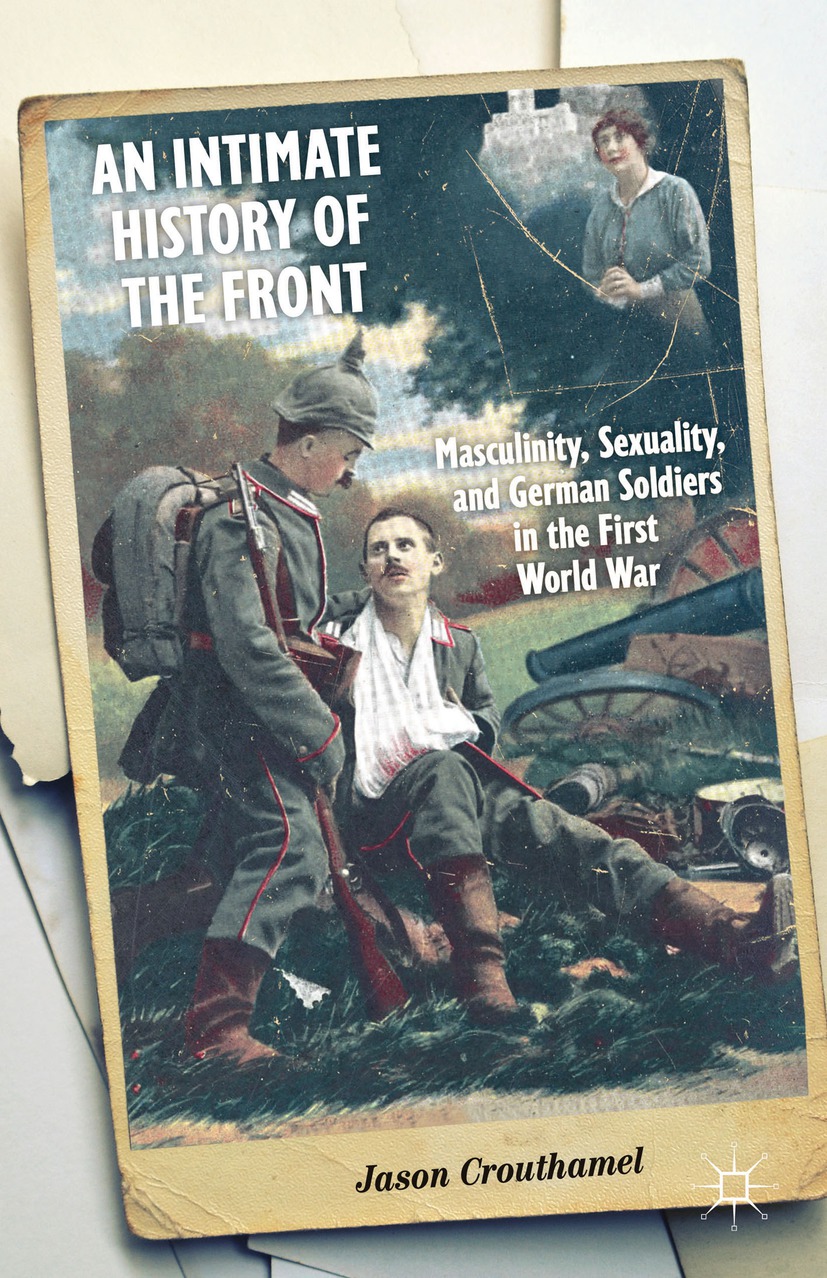

Perceptions of masculinity constructed by enlisted men and officers at the front were much more ambiguous than prevailing media and military ideals suggested. Soldiers’ narratives of the war experience in front newspapers, letters home, and diaries reveal the complex ways soldiers on the Western and Eastern fronts perceived ideals of masculinity, expressed love, found intimacy, and experienced sex. In my book, An Intimate History of the Front: Masculinity, Sexuality, and German Soldiers in the First World War, I analyze how German soldiers in the Great War actively negotiated, bolstered, and challenged prevailing masculine ideals in an effort to survive the traumatic experience of modern war.

Perceptions of masculinity constructed by enlisted men and officers at the front were much more ambiguous than prevailing media and military ideals suggested. Soldiers’ narratives of the war experience in front newspapers, letters home, and diaries reveal the complex ways soldiers on the Western and Eastern fronts perceived ideals of masculinity, expressed love, found intimacy, and experienced sex. In my book, An Intimate History of the Front: Masculinity, Sexuality, and German Soldiers in the First World War, I analyze how German soldiers in the Great War actively negotiated, bolstered, and challenged prevailing masculine ideals in an effort to survive the traumatic experience of modern war.

In their front newspapers and letters, many men criticized the masculine image of the self-controlled, emotionally disciplined warrior. As a result, men searched, often desperately, for emotional support and intimacy, which included confessions of vulnerability and hunger for nurturing and compassion. They began to incorporate these ‘feminine’ emotions into their conceptions of idealized masculinity. Some sought, with mixed success, greater intimacy with women. Others craved intimacy with other men under the guise of comradeship. For soldiers in the First World War, comradeship was essential for surviving psychological stress. It provided an acceptable way for men to express emotional support and compassion, and it gave them a sense of familial bonds and belonging that was crucial for survival as men felt both isolated and distant from their traditional social structures. However, ‘comradeship’ was not defined homogeneously. It was contested and appropriated by different social and political groups, and it was used as a basis for exclusion, especially by the political right, and later, by the National Socialists, who defined political and racial ‘enemies’ as outsiders to the ‘national community.’

At the same time, ‘comradeship’ became an umbrella concept under which both heterosexual and homosexual men with different perceptions of emotional and sexual norms found inclusion, at least from their point view, as ‘real men.’ Soldiers who saw themselves as ‘real men’ and ‘good comrades’ sometimes fantasized about adopting feminine characteristics, or even experimented with homosexual love. This normalization of ‘feminine’ emotions of compassion and nurturing created a safer space for men to express love, allowing for experimentation with different emotional and sexual paradigms. The brutality of war made some men feel repulsed by what they saw as innately masculine characteristics, and they envied the ‘softer’ characteristics of the ‘other sex.’ ‘Feminine’ emotions, once condemned as ‘soft’ and weak, were now seen as essential to providing emotional support to comrades under stress. For example, in a 1918 poem titled “We poor men!” in the front newspaper Der Flieger (The Flyer), a sergeant turned poet named Nitsche longed for an existence without bombs, trenches, and horrifying front-line conditions. Lamenting the images of bombed-out landscapes and the tedium of military drill, Nitsche envied women’s “sweet smiles” and beauty. He refrained: “We poor, poor men are so completely wicked. I wish I were a girl. I wish I weren’t a man!” Nitsche fantasized that he could transform into a woman. He dreamt of cooking wonderful meals and gracefully moving about: “My breasts would arch themselves as I waltz about in high heels,” and he ended the poem with: “For a long time I could kiss the entire company, and I would certainly not absorb the fragrances that come out of the frying pan – Oh, if I only were a girl, why am I a man!” Nitsche’s poem pushed emotional transgression to its logical conclusion, as it exhibited a soldier’s fantasy, in the safe zone of humor, about actually changing his gender in order to escape the expectations of being a “wicked” man. He fantasized that he could be a better comrade as a woman, providing love and comfort to men who needed it.

The desperate need for ‘feminine emotions’ of love and nurturing provided a space for men to express their desires. While the correspondence between many couples revealed a widening gulf between traumatized men and women, other couples grew closer as they turned their letters into a kind of secret world where they could explore intimacy. Many men, such as the aforementioned Kurt K., confessed feelings of vulnerability, emotional dependence, fear, and love that may have been otherwise taboo in the confines of the heroic ideal. In the case of Fritz N. and his girlfriend, Hilde, letters became a medium for developing an emotionally-rich and sexually-charged fantasy life. For example, in one letter, Fritz advised Hilde on how to sneak into his trench at night:

I must explain to you how you can find me! We could meet in a shack in a deep-cut trench. You must be quiet, very quiet, because there are so many people everywhere. Radio operators, telephone specialists and other soldiers – I’m not alone in my bedroom: the captain lies next to me and he’s such a light sleeper!! And it’s so terribly cold! You must firmly cuddle me.

Other times, soldiers’ search for intimacy translated into homosexual desire. Similar to their heterosexual comrades, homosexual activists glorified the nurturing ‘feminine’ side of comradeship, as long as there was no ambiguity that they were indeed ‘real men.’ In the booklet Male Heroes and Comrade-Love in War, front veteran Georg Pfeiffer, a member of one of the earliest homosexual rights organizations, the ‘Community of the Self-Owned’, argued that “physiological friendship” was always the foundation for heroism, courage, and sacrifice displayed in war. “Friend-love” promoted by the ancient Greeks, he argued, “was the equivalent of modern ‘camaraderie’,” and it bonded the soldier to the nation:

Only the super-virile ‘superman,’ whose nature it is to also possess female characteristics and above all the drive toward physiological friendship, the love for a friend, towers so high above the masses […] We only wanted to prove that comrade-love and male heroism were the most valuable driving forces in all wars, which effected the complete devotion of one’s own person to leader and friend, to the fatherland!

Pfeiffer also compared the Confederate States of America during the U.S. Civil War to the German Army in 1914-1918, arguing that both were “united by the true spirit of comrade-love,” a pure, noble value that had much greater spiritual meaning and was considered more manly than what he saw as the hollow heterosexual relationships with women on the home front.

Homosexual men found comradeship to be an ideal prism through which to define their emotions and sexuality. Many homosexual veterans embraced martial masculinity and contested the exclusively heterosexual image of the warrior male. The war experience emboldened homosexual men to contest Paragraph 175, the German law that criminalized sex between men, and combat stereotypes of homosexuals as ‘deviant’ outsiders. Further, the front experience triggered debates between already disparate homosexual rights organizations over whether homosexual men were a partially ‘effeminate’ third sex, as homosexual rights pioneer and sexologist Magnus Hirschfeld theorized, or whether the war proved that ‘masculine’ homosexual men were the ideal warriors for civil rights and postwar integration. As a result of their experiences of the war, homosexual men found a new language and image to combat marginalization and redefine themselves as ‘normal,’ or as some even saw it, more masculine than their heterosexual comrades, within a framework of militarized masculinity. As one front veteran writing for the homosexual rights newspaper, Die Freundschaft, asked in 1921: “Are we enemies of the state? Answer: no, because we want to be loyal national comrades, who want to have an extensive share of the blood in the reconstruction of Germany.”

Between 1914-1918, men encountered a wide spectrum of emotions and experiences that demand further historical analysis. The war triggered fundamental changes in how men imagined the warrior image. It also profoundly changed how they perceived and expressed emotions and desires. The meanings of these new emotions, and conceptions of masculinity and sexuality, would be fought over by social and political groups after the war ended. But for many ‘ordinary men,’ the effects of the war eluded categorization and were more complex than political, medical, and military authorities imagined.

Jason Crouthamel is an associate professor of history at Grand Valley State University in Michigan. He has published on the history of psychological trauma, memory and masculinity in Germany during the age of total war. He is the author of An Intimate History of the Front: Masculinity, Sexuality and German Soldiers in the First World War (Palgrave Macmillan, 2014) and The Great War and German Memory: Society, Politics and Psychological Trauma, 1914-1945 (Liverpool University Press, 2009). He is also the co-editor, with Peter Leese, of the companion collected volumes Psychological Trauma and the Legacies of the First World War and Traumatic Memories of World War Two and After (both with Palgrave Macmillan, 2016).

Jason Crouthamel is an associate professor of history at Grand Valley State University in Michigan. He has published on the history of psychological trauma, memory and masculinity in Germany during the age of total war. He is the author of An Intimate History of the Front: Masculinity, Sexuality and German Soldiers in the First World War (Palgrave Macmillan, 2014) and The Great War and German Memory: Society, Politics and Psychological Trauma, 1914-1945 (Liverpool University Press, 2009). He is also the co-editor, with Peter Leese, of the companion collected volumes Psychological Trauma and the Legacies of the First World War and Traumatic Memories of World War Two and After (both with Palgrave Macmillan, 2016).

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com