In 1897, sexologists Havelock Ellis and John Addington Symonds published Sexual Inversion, a path breaking work on same-sex desire. In the early stages of their correspondence about the book, Ellis explained that it had been Italian sexological works that had first prompted his interest in the scientific study of human sexual behaviour, and convinced him of the critical role of sexuality in the lives of men and women alike. If Westerners have increasingly thought of sexuality as an integral part of their self-definition during the 20th century, some of the credit must surely go to these Italian pioneers.

Indeed, Italian thinkers such as the renowned criminal anthropologist, Cesare Lombroso, and the anthropologist, Paolo Mantegazza, played a pivotal role in shaping the new ideas about sexuality that were emerging in the second half of the nineteenth century in Europe. Sexual desires, they maintained, were not vices to be denounced by religious authorities or crimes to be condemned by the courts; they were, rather, both innate and environmentally determined. Yet despite the fact that these authors produced some of the most significant accounts of the modern idea of sexuality, scholars have overlooked the history of sexuality in Italy in this vital period. While historians have studied different aspects of the changing attitudes towards sexuality in Italy in various epochs, from Roman Antiquity to the Renaissance and the Fascist regime, the history of sexuality in nineteenth-century Italy has long been neglected.

To fill this startling gap, Valeria P. Babini, Lucy Riall, and I co-edited a collection of essays, Italian Sexualities Uncovered, 1789 – 1914 (Palgrave, 2015), which explores the history of sexuality in Italy throughout the long nineteenth century. All the contributors met originally at an international workshop held at the University of Bologna in 2012. As the title of our volume indicates, we hoped to uncover what is usually hidden in the general accounts of modern Italian history.

Italian Sexualities Uncovered is an interdisciplinary volume; it brings together a group of fifteen international historians and literary scholars to explore a wide range of topics. The volume consists of five parts divided thematically rather than chronologically. The first part explores how the histories of sexuality, politics and the family were intertwined in the nineteenth century. The second part of the volume explores the sexual attitudes of different classes and social groups. Part three focuses on women in the private and the public sphere. The fourth part explores the history of same-sex desires while the final part of this volume focuses on sexuality and marriage. Though it is impossible to summarise all fifteen essays contained in the edited volume within the constraints of a blog, a brief look at the volume reveals the richness of emerging scholarship in the field, as well as a number of promising directions for future research.

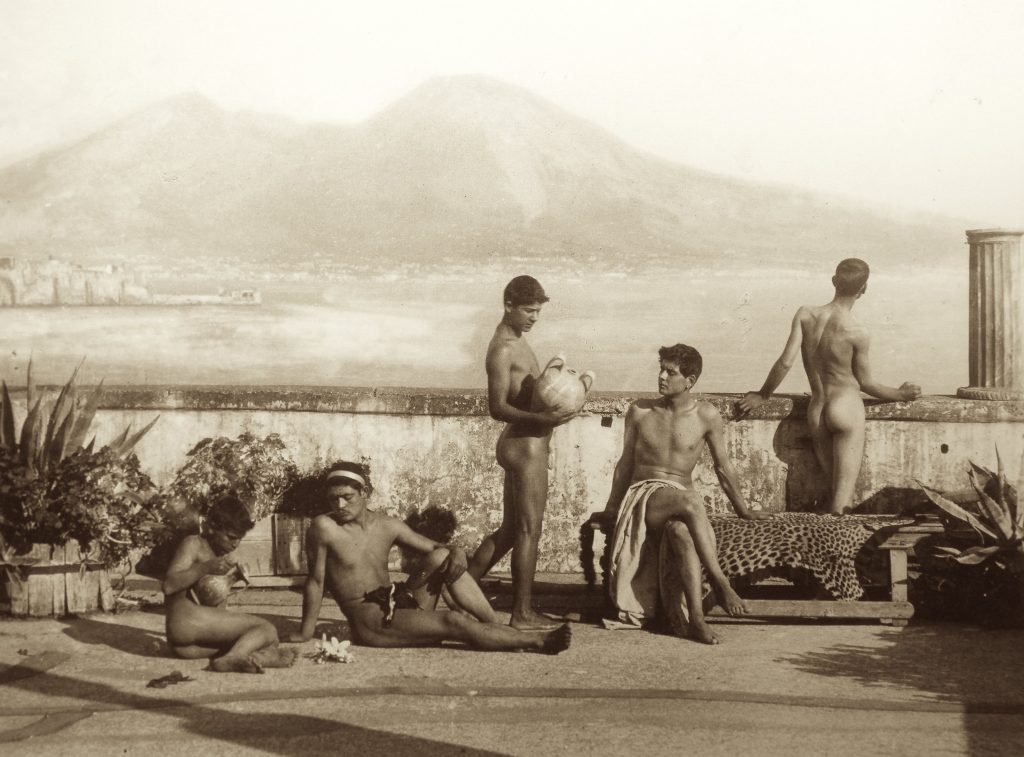

Several contributors make good use of the turn toward transnational analysis in the history of sexuality. Ross Balzaretti, Roberto Bizzocchi, Sean Brady and I have thus considered foreigners’ views of Italian sexual morality and the sexual encounters between Italians and the British. In part this concern with transnational links between the UK and Italy corresponds to the editors’ and contributors’ interests, but it also reflects the state of the field. In his essay on Italian sexual customs and family life during the revolutionary and Napoleonic periods, Roberto Bizzocchi ponders just why foreign travellers were given to condemning the private sexual morality and lifestyle on display in Italy. Bizzocchi suggests that foreigners’ central preoccupation, their obsession even, was with the figure of the cicisbeo, the male consort of a noble woman, who eventually came to symbolise the ways in which allegedly authoritarian rule had rendered men sexually corrupt. My own essay explores some of the old stereotypes that had associated the south of Italy with male same-sex practices; the views of homosexual foreign travellers such as Oscar Wilde and Norman Douglas on the same topic; and the phenomenon of British homosexual sex tourism in the Mezzogiorno. It draws attention to southern Italian local traditions such as the femminiello (men who wore women’s clothes and were integrated into the local community) and institutionalised yet transient homoerotic experiences during adolescence, which were meshed with the phenomenon of homosexual tourism. Sean Brady explores cross-class masculine comradeship in Venice. For, as Brady shows, Venetian working-class cultures of masculinity, in particular that of the gondoliers, captured the imaginations of British literary homosexual men, such as John Addington Symonds and Horatio Brown.

Along with the national, the volume transcends other kinds of boundaries. It challenges, for example, the separation between public and private. It contains a number of essays, such as those by Lucy Riall and Valeria P. Babini, that show how the private and the political spheres are linked in modern Italian history, sometimes in highly contradictory ways. Lucy Riall considers the private lives of prominent patriots, notably Massimo d’Azeglio, Giuseppe Mazzini and Giuseppe Garibaldi, during the Risorgimento, the movement for Italian unification that culminated in the Kingdom of Italy’s establishment in 1861. Riall explores the history of sexuality behind the rhetoric of nationalistic politics, where the latter vaunted the ideals of family and domesticity. She shows us that such ideals acquired a patently political function, although the private experiences of the Italian patriots did not always conform to the nationalistic rhetoric they were so eager to promote. Valeria P. Babini studies the topic of sexuality and maternity in relation to three ‘new women’: Sibilla Aleramo, Maria Montessori and Linda Murri. Despite the fact that women’s sexuality had been regarded as a taboo and was sacrificed to the myth of motherhood by the Catholic Church, politicians and even medical doctors at the turn of the twentieth century, some ‘new women’ raised awareness about women’s desire for sexual freedom.

Showing that there is much to gain by challenging rigid historical periodization, itself often a feature of established political history, a number of essays survey the long nineteenth century, for example Linda Reeder’s chapter on the Italian husband. Reeder explores how ideas of masculinity were associated with medico-scientific ideas of being healthy. At the same time our volume has highlighted some key events that have brought about fundamental changes in the history of sexuality in modern Italy – the promulgation of the Civil and Zanardelli Penal Codes, for example. Recounting the memorable murder of Giovanni Fadda in Rome in 1879, Mark Seymour explores the period between Italian unification and the implementation of the Zanardelli Penal code. In his essay, Seymour explores the sexual entanglements between the world of the circus and the wealthy classes. Seymour’s account delineates legal, journalistic and popular responses to sexual affairs crossing the boundaries between different classes, and reveals how respectable middle-class women might pursue sexual liaisons with lower-class men.

Much of the previous historical research on nineteenth-century Italy has focused on the history of prostitution (quite often in regional contexts) and on the role of law and science in constructing the notion of a healthy and normative sexuality. Gay and lesbian history has only started to develop in the last five years. Quite often these are top-down histories, and much has still to be done to reveal the sexual histories of common people, their experiences, how they reacted to legal, religious or medical impositions and constrains. To date there has been no overarching study into the continuities and discontinuities of the history of sexuality in the long nineteenth century in Italy. With Italian Sexualities Uncovered, we hope to have offered a starting point for further research. Of course, this edited collection, like any other volume of a similar nature, cannot pretend to be exhaustive, but the editors trust that it will encourage further research in the coming years.

Dr. Chiara Beccalossi is a Senior Lecturer in Modern European History at the University of Lincoln. Her research interests range across the history of sexuality, the history of medicine and the history of human sciences in Europe, in particular Italy. Chiara’s first book was Female Sexual Inversion: Same-Sex Desires in Italian and British Sexology, c. 1870–1920 (2012), which explored how medical men in Italy and Britain pathologised same-sex desires. She has also co-edited Italian Sexualities Uncovered, 1789-1914 (2015) with Valeria P. Babini and Lucy Riall, A Cultural History of Sexuality in the Age of Empire (2011) with Ivan Crozier, and has published numerous articles in history of sexuality and medicine. She tweets from @ChiaraBcc

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com