“Dance! dance! dance! in joyful syncopation to the maddening rhythm of the saxophone! Worship at the throne of the great god Jazz with the girl of your dreams!” intoned the advertisement for the February 6, 1924 Science Dance at Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario. This “humorously written notice” promised students, “One night when the earth seems far away and the pulses beat fast to the sensuous music of the latest waltzes and the most tempting fox-trots.”

The February dance ignited a conflict between Queen’s University students and a local newspaper, the Daily British Whig, when it published an exposé of “the dancing evil” and its “depraving effect upon the young.” The exposé’s author worried about the sexual atmosphere in Kingston and called for “drastic action” to prevent “familiarity” at city dances from becoming “detrimental to the rising generation.” He suggested “young couples dancing a fox-trot in a close embrace” were actually engaging in “one big ‘petting party‘,” and criticized Queen’s students for holding “half-dark” dances on campus.

In a defensive letter to the editor, published the day after the Whig‘s exposé, the Queen’s Alma Mater Society distanced Queen’s from the immorality of downtown nightlife and sexualized dances like the foxtrot. The letter emphasized the waltz’s ongoing popularity at “wholesome” campus dances. In response, the Whig published a follow-up article claiming that students were actually dancing the foxtrot more than the waltz, calling into question the moral atmosphere on campus. Students demanded the anonymous reporter “cease this constant slurring of a wholesome student activity” and apologize. When they identified F. B. Pense as the reporter responsible, the situation escalated out of control: a group of students retaliated by kidnapping Pense from his home and subjecting him to a trial in a student court.

Why did dancing lead to conflict between university students and local media and what can this tell us about sexual mores in early-twentieth-century Ontario?

One way to understand this conflict is to see it as a window into youth culture and changing sexual values and notions of respectability. Isolated to some degree from the world of adults, but still subject to public scrutiny and the guardianship of university officials, Canadian university campuses served both as spaces for the reinforcement of mainstream heterosexual norms, and as youth-dominated spaces where those same norms could be contested and reshaped.

During the early decades of the twentieth century, university dances were one of the main spaces for heterosocial interaction and sexual experimentation at Queen’s. They provided opportunities for socially sanctioned “public displays of physical contact between men and women” in the pre-war era, and became flashpoints for tension over respectable heterosexual behaviour when youth norms and styles evolved in the 1920s. Older Canadians responded to the growing popularity of “such ‘fevered’ dances as the tango, the fox trot … and the Charleston” with growing alarm and began to condemn them as morally corrupting. Pense’s journalism was just one indicator of a growing divide between campus youth culture and the mores of older Kingston residents.

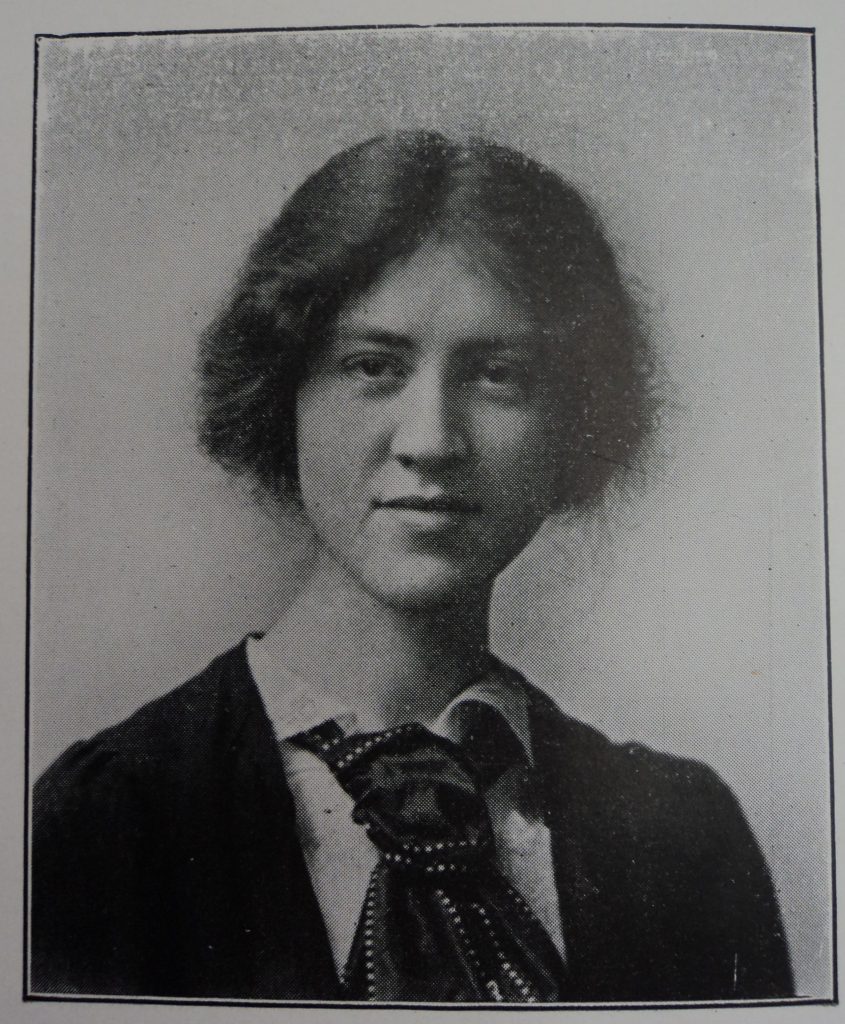

The generational conflicts over dancing and sexual expression that came to a head at Queen’s in the 1920s were an escalation of pre-war student frustration at restrictions on co-ed socializing. In 1911, the University Senate caused controversy when it considered reducing the number of dances. The length of dances also became an issue. Mildred Clow’s 1913-1914 scrapbook reveals she was used to dancing late. At the Medical Dance in November 1913, she danced until after two in the morning, but she reported that the Junior Year Dance in February 1914 “was much too short for the Senate raised a fuss + we had to stop at 12 o’clock.” By 1920, informal Friday night dances that ended at 11 had become a weekly event at Queen’s, but the Senate refused to extend them to midnight until students went on strike in 1928 over “condescending treatment” by university officials.

Lighting at dances also became a source of tension as administrators sought to maintain public propriety. Through the 1920s, campus dances remained closely supervised by adults. Levana, the women’s student society, also tried to prevent female students from attending un-chaperoned city dances. In these contexts, some Queen’s students took advantage of dimly lit public spaces to find privacy in public. When George Wilson graduated in 1918, his peers joked that his success as an electrical engineer might ruin the “dimly lit ‘sitting-out rooms’” at campus dances.

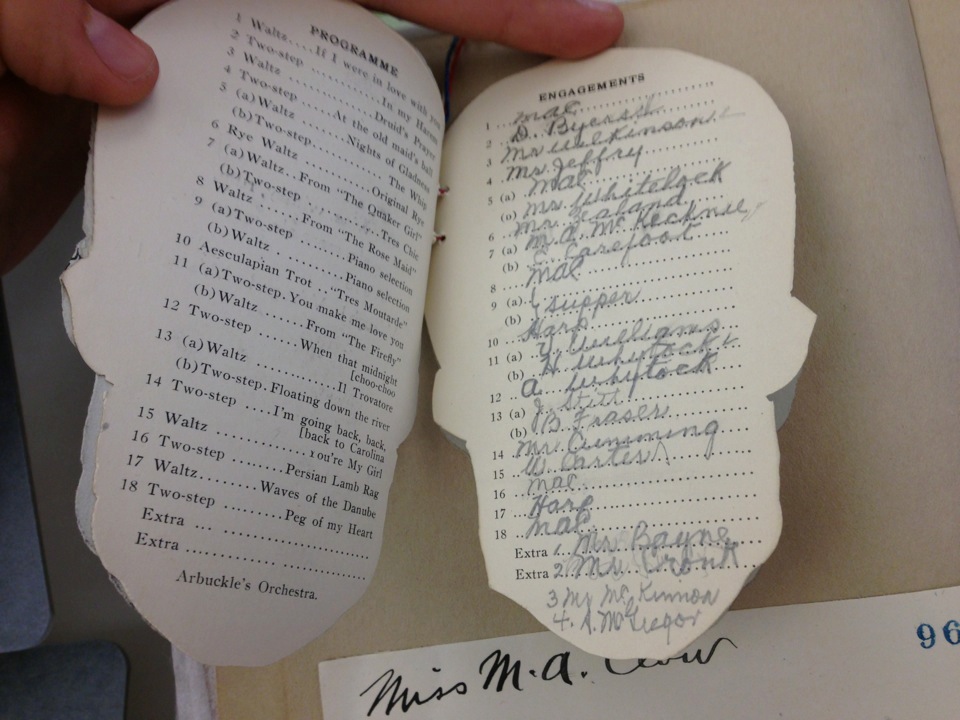

Even as adults attempted to supervise Queen’s students, students regulated their own dances through the use of dance cards. Produced in miniature for each dancegoer, the cards listed the evening’s scheduled dance numbers, with corresponding spaces so students could track their commitments. While students would attend a dance with a specific partner, they would dance with many different partners over the course of the evening. In the 1920s, social butterfly Marjorie Purtelle and her friends “wanted to dance with somebody different every dance,” and thought dancing a “straight program” with one person was “the most boring thing in the world.” As Marjorie recalled, “when you went to a dance with anyone, if he booked you up for too many dances you didn’t go with him again.”

Despite pushing against adult rules, Queen’s students nonetheless drew behavioral lines, and saw themselves as being on the right side of them, even if adults disagreed. The 1923-24 Queen’s Journal editors insisted Queen’s students “are capable of seeing to it, do see to it, and will always see to it, that nothing of the objectionable creeps into their happy Social Evenings.” This sense of propriety and school pride led to the conflict with the local media.

On February 19, 1924, a group of students responded to F.B. Pense’s criticism of student conduct in the Daily British Whig by “forcibly taking him from the vicinity of his home to the university gymnasium, where they submitted him to a student-court trial” involving various “stunts.” Queen’s University quickly tried to arrange an “amicable settlement of the matter,” but Pense demanded “personal damages” and a “written apology from the ringleaders.” After the Attorney-General of Ontario learned of the events, he demanded that the local authorities discipline the culprits. Six students were summoned before the Police Magistrate. Although their lawyer argued it was just a “college prank,” they were each fined “$25 and costs … with the option of one month in jail,” and given a “stern lecture” by the Magistrate.

Students’ response to Pense’s criticism of campus dance culture was meant to protect their own reputations against outside criticism. Queen’s students saw themselves as respectable, middle-class Canadians—an identity that properly deployed heterosexuality was intended to reinforce. By questioning the morality of students’ behaviour, Pense threatened their ability to claim that respectable identity and the privileges it carried when they entered Ontario society. At the same time, by focusing on dances, Pense threatened one of their main opportunities to interact and experiment with members of the opposite sex. Becoming a respectable Canadian was a near-universal objective during this period, and the struggles over dance culture at Queen’s are best understood as part of a generational conflict over how to achieve it.

Renata Colwell graduated from Queen’s University, Canada with a BA (Honours) in History and is currently completing a Juris Doctor at the University of Victoria Faculty of Law. This essay draws on material from her Honours thesis, “Youth Must Have its Fling”: Dating, Courtship, and Heterosexuality at Queen’s University, 1910-1955.

Renata Colwell graduated from Queen’s University, Canada with a BA (Honours) in History and is currently completing a Juris Doctor at the University of Victoria Faculty of Law. This essay draws on material from her Honours thesis, “Youth Must Have its Fling”: Dating, Courtship, and Heterosexuality at Queen’s University, 1910-1955.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com