Interview by Alexie Glover

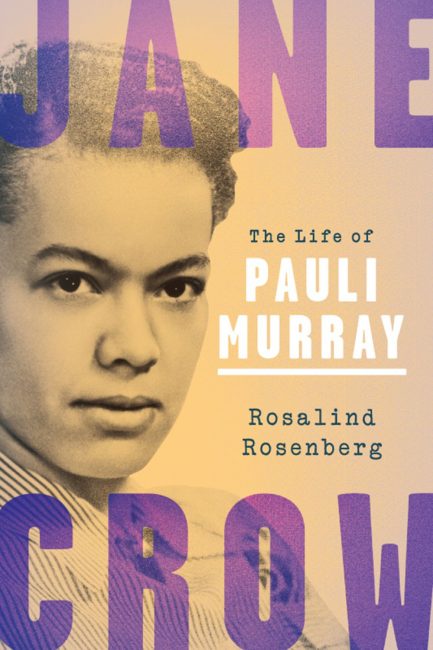

Rosalind Rosenberg’s book Jane Crow: The Life of Pauli Murray (Oxford University Press, 2017) examines the life of Pauli Murray (1910-1985), a civil rights activist, feminist, lawyer, and priest. Murray may not be the most famous civil rights figure, but she was responsible for masterminding the strategy successfully used by Thurgood Marshall in Brown v. Board of Education. She also helped Ruth Bader Ginsburg develop the argument that the Fourteenth Amendment protects women as well as black Americans. However, Rosenberg’s book demonstrates that Murray was more than just a brilliant lawyer. In a break from previous biographies, Rosenberg describes Murray’s struggles with her gender identity. Rosenberg details how Murray tried to persuade medical professionals that she was inherently masculine. She even asked for testosterone injections, long before Harry Benjamin began his endocrinology practice in the United States. Rosenberg demonstrates that Murray was truly a person ahead of her time.

Alexie Glover: What struck me about this biography was how relevant Murray’s life is to this particular moment in the US. At a time when the Black Lives Matter Movement is burgeoning and when bathroom bills are constantly discussed, what can Murray’s life teach us? Why was it important for you to revisit her life from a historian’s perspective?

Rosalind Rosenberg: Today’s struggles often fail to confront the intersection of race and gender. The most recognizable names in the Black Lives Matter movement are almost always male shooting victims; the trans people who seek to use the bathrooms in which they feel most comfortable are almost always white. But for Murray, race and gender oppression could never be disentangled. That’s why she coined the phrase Jane Crow, a term that covered not only her battle against racial and gender discrimination, but also her secret struggle over gender identity—three issues we’re still grappling with today, many decades later.

In the first half of the twentieth century, signs on public bathrooms in North Carolina, where Murray grew up, suggested that there were three genders: “Men,” “Women,” and “Colored.” If Murray had ever used the one that felt most natural (the one marked “Men”), she would have been lynched, not for gender transgression, but rather for defying state-imposed racial segregation. The North, to which Murray fled after high school, proved only marginally more congenial. The police in Bridgeport, Connecticut, came close to arresting Murray one day when she dared to use the men’s bathroom at a train station. Murray’s race attracted the police’s attention, but her crime that day was in defying gender convention in her choice of a public bathroom. Examining Murray’s life today reminds us that today’s battles over bathrooms—especially the one playing out in North Carolina—provoke fierce passions because they are about more than gender, they are echoes of older (and by no means forgotten) battles over race.

AG: Some assume that the reason black women’s history has been neglected is due to a lack of primary sources. However, you mention throughout the book that Murray kept meticulous personal records. Murray obviously viewed her life as consequential, why do you think it has taken this long for a historian to dive into her extensive archive?

RR: Actually, historians began research in Murray’s papers as soon as they became available at the Schlesinger Library in the mid-1990s. For the most part, however, scholars avoided any discussion of Murray’s struggle over gender identity. Some regarded that struggle as unconnected to what they considered Murray’s more important public contributions to civil rights, feminism, jurisprudence, and theology. Others worried that any examination of Murray’s private battles would sully her reputation as a civil rights leader and priest. But over time, the LGBTQ movement has brought legitimacy to discussions of sexuality and gender identity. That legitimacy made publication of my book possible.

AG: Can you tell us about the archival material you found most captivating? Murray lived an incredible life. I can only imagine how exciting the research for this project must have been.

RR: Murray’s notes on encounters with doctors are without question the most riveting material in her papers. Murray made detailed, usually typed, notes on her visits to doctors and hospitalizations for acute emotional distress from her 20s into her 40s. Reading her questions and the doctors’ answers, one cannot help but be moved. She asked doctors to give her testosterone. They refused. She implored a surgeon to search for undescended male testes while performing an appendectomy. He found none. No one was willing to help Murray change her body to more closely correspond to her inner sense of maleness. Worse, most of the doctors Murray consulted believed she was mentally ill. One diagnosed schizophrenia on the grounds that Murray was suffering from the delusion that she was a man. Most people would have been crushed by this treatment; Murray turned it into an attack on conventional ideas about race and gender that others took to be natural.

AG: Transgender history often encounters the problem of historians reading their modern understandings of gender diversity into their sources. Many of your references to Murray’s gender identity, or inherent feeling that she was male, come from her personal papers. Do you think your knowledge of modern transgender identity impacted your analysis? Did you find it challenging to represent Murray’s complex identity struggle without imposing contemporary understandings of trans categories upon her?

RR: Not everyone agrees that Murray was transgender. In fact, when I first began research in Murray’s papers, I was not sure that today’s understanding of gender diversity fit Murray’s life. The term “transgender” is a recent coinage, and even the older “transsexual” appeared only in 1949. Was it legitimate for me, I wondered, to use terms not then in existence to analyze Murray’s life? I resolved this dilemma by trying to understand Murray on her own terms, using her own language. That is why I eventually decided to use the pronouns Murray used (e.g., she, her), rather the ones that a trans man today would use and ask others to use. Restricting myself in this way, I nevertheless found strong evidence that Murray struggled with what we today would call a transgender identity.

She did not have our language, but she read everything she could that might help her understand her strong identification as male. Discovering the writings of “sexologists” in the early 1930s, she embraced the work of Havelock Ellis, who argued that everyone is partly male, partly female. Ellis also posited the existence of “pseudo-hermaphrodites,” people who have the external characteristics of one gender and the internal characteristics of the other. Murray embraced that label. When doctors finally persuaded Murray that she did not have internal male sex organs, she concluded that her sense of inner maleness must come from having a male brain. Nothing ever deflected her from her core belief that she was inwardly male.

AG: Recently historians of late-twentieth century American sexuality have worked to complicate the notion that religion was a negative force in the lives of LGBTQ individuals. Murray certainly does not fit this dominant narrative. Can you speak more to the role that her religious beliefs, and ultimate ordination, played in shaping her sexuality and gender identity?

RR: Murray deplored the misogyny she saw displayed in the Episcopalian church, the church into which she was born and raised by her deeply devout family. For a time in her 20s she abandoned religion, but she returned in her 40s, finding in the rituals of the Episcopal service solace in an otherwise hostile world. She also fell in love with a fellow Episcopalian, Renee Barlow, who campaigned with Murray against gender discrimination in their church for fifteen years. When Barlow died in 1973, a grief-stricken Murray rededicated herself to their joint campaign and in 1977 became the first black woman to be ordained a priest in the Episcopal Church.

Murray also reinterpreted theology in feminist terms wherever possible, often by historicizing church doctrine. She downplayed the importance of the Adam and Eve story, and focused instead on the opening of Genesis. In the Hebrew version, she liked to point out, God created human beings, not ‘man.’ As a priest, Murray came to believe that God had put her on earth to serve as a bridge in a divided world. The true Christ, she insisted, was one in whom there was no black or white, no male or female, no North or South—only Spirit and Love and Reconciliation. Having come of age in a day in which her body could never be made to square with her inner sense of self, she found refuge in later life in the more abstract, spiritual language of a theology she reinterpreted to allow for a greater inclusiveness.

Alexie Glover is an MA student at the University of Victoria, where she graduated with her BA in history in 2016. She specializes in the history of sex, sexuality, and gender in North America. Her work explores the construction of trans and gender non-conforming identity in the twentieth-century United States. She is an assistant editor for the Graduate History Review. She is a 2017 Master’s Degree Scholar for the world’s first Chair in Transgender Studies.

is an MA student at the University of Victoria, where she graduated with her BA in history in 2016. She specializes in the history of sex, sexuality, and gender in North America. Her work explores the construction of trans and gender non-conforming identity in the twentieth-century United States. She is an assistant editor for the Graduate History Review. She is a 2017 Master’s Degree Scholar for the world’s first Chair in Transgender Studies.

Rosalind Rosenberg is Professor of History Emerita at Barnard College, Columbia University. She is the author of Jane Crow: The Life of Pauli Murray (Oxford University Press, 2017), Changing the Subject: How the Women of Columbia Shaped the Way We Think About Sex and Politics (Columbia University Press, 2004), Divided Lives: American Women in the Twentieth Century (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1992), and Beyond Separate Spheres: Intellectual Roots of Modern Feminism (Yale University Press, 1983).

Rosalind Rosenberg is Professor of History Emerita at Barnard College, Columbia University. She is the author of Jane Crow: The Life of Pauli Murray (Oxford University Press, 2017), Changing the Subject: How the Women of Columbia Shaped the Way We Think About Sex and Politics (Columbia University Press, 2004), Divided Lives: American Women in the Twentieth Century (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1992), and Beyond Separate Spheres: Intellectual Roots of Modern Feminism (Yale University Press, 1983).

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com

Thank you for calling my attention to Murray and to this book.