Charlotta Forss

Modern iterations of the sauna – and especially the gay sauna – have been highlighted as spaces where societal norms might be transcended and at the same time moral anxiety heightened. What is less recognized today is that the hot-bath has a long history as a place of moral and sexual contention. A closer look at the anxiety and fascination surrounding the early modern Swedish sauna in the accounts of foreign travellers clearly shows this. These accounts reveal early modern conceptions of moral behaviour in relation to undress to be much more malleable than what has hitherto been appreciated. There is a need to pay closer attention to the extent to which early modern Europe understood morality to be influenced by regional customs.

In early modern Sweden bathing was a part of everyday life. There were public and private hot-steam baths, or saunas, in the cities and throughout the countryside. Some were intended only for men or women, but there were also saunas where men and women bathed together. In a sauna with only male bathers, female servants would be attending. While the bathers might be naked, the attendants were dressed in linen garments. However, and as has been noted elsewhere, the early modern mindset included both complete absence of clothing and partial undress in the category “naked”. Thus, even an all-male sauna with female attendants could challenge propriety. These saunas were, on the one hand, part of the fabric of everyday life. On the other hand, the sauna was a morally contested space that heightened some observers’ concerns about and interest in undress and physical proximity.

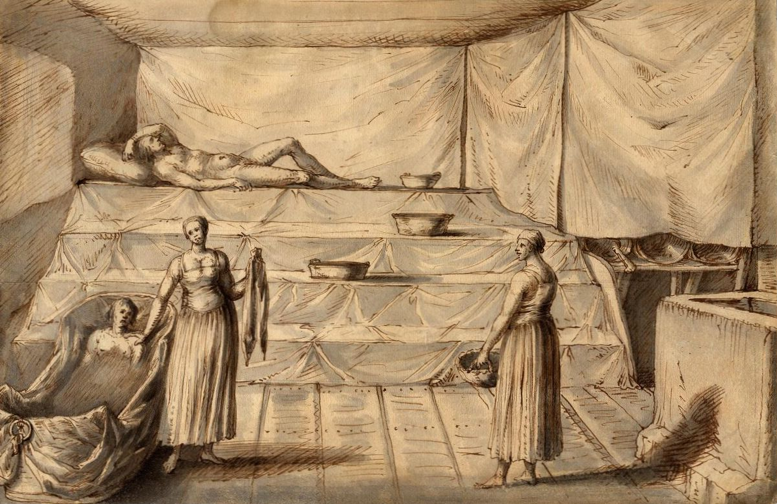

Indeed, in report after report, early modern travellers to Sweden wrote home about the undress they had witnessed in the saunas. For instance, the Italian naturalist and diplomat Lorenzo Magalotti included a scene from a sauna when illustrating his narrative of his visit to Stockholm in 1674. In Magalotti’s sketch, a fully unclothed man rests on a bench at the back of the sauna while in the foreground, two female attendants wearing linen garments tend to the bathers.

With accounts and illustrations like Magalotti’s, early modern travellers to Sweden voiced both fascination and a moral distancing from the local custom. In this way, the sauna provided travellers to Sweden with the curious and strange that was expected in an early modern travel narrative about foreign lands. At the same time, the sauna created an actual and conceptual space where the traveller could both join in with and comment on the local variability of eroticism.

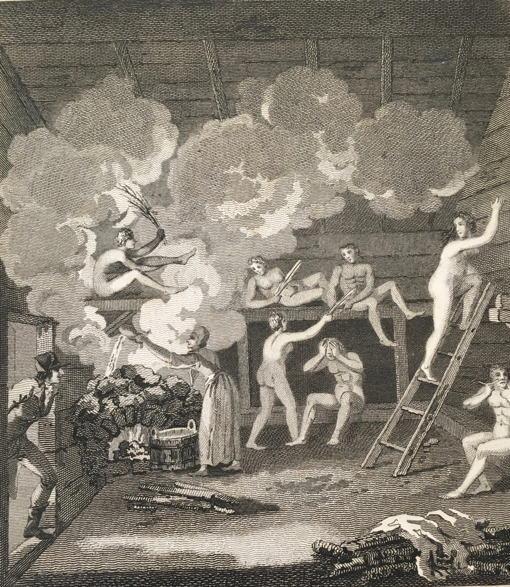

That the early modern Swedish sauna could catch the imagination of a visitor is seen in the account of the Frenchman Charles Ogier, who was in Stockholm on a diplomatic mission in 1635. Ogier provided his audience back home with a commentary of the sauna as he had experienced it:

sweat flowed from the whole body, and if it did not come forcefully enough, one brought it forth by whipping with a bunch of birch twigs. This service to the bathers was strangely enough made by girls, dressed only in linen garments; it seemed that they without a feeling of shame – indeed maybe without understanding, that there was anything to feel shameful about – treat the naked men, rub them with the fingertips, wipe the dirt from their body and head, lather them, rub them, and wash them. Here men and wives and young girls come together among each other. The women have only linen on. The men hide their secret parts only with a bunch of birch twigs. Custom and benefit have here driven away shame. Not even the most chaste women hesitate to visit these hot bathhouses, rather going there with husband and children.

An undertone of wonder pervades Ogier’s description: he is clearly describing a visit which made an impression on him and which he anticipates will impress his readers too. Ogier’s perspective of the sauna was that of an outsider, even though he also partook in the bathing rituals. This created tensions, as demonstrated in an account by one of Ogier’s countryman, an anonymous French manservant who visited Sweden in the middle of the seventeenth century. The manservant bragged in his journal that “I have been there [to the bathhouses] more than twenty times, not because I needed it but to look at the beautiful and wholly naked girls, and also to see what the practice was.” He goes on to say that he and his countrymen used to try to tickle the Swedish women in the sauna, but that they would promptly respond by pouring ice-cold water over them. In his account we get an indication that one could “need” the sauna, referring to the fact that these institutions were places for medical treatment as well as enjoyment. The focus, however, is on the excitement the Frenchman felt at the proximity of the undressed girls. He seems to have interpreted the physical closeness of the sauna together with the scarcity of dress as an invitation to further intimacy.

However, it is clear that the visitors did not think that the locals shared their impression of the erotic nature of the sauna. Much like later orientalist travellers to the Ottoman Empire, who were eager to be fascinated by the Turkish baths, the visitors to the Nordic saunas expected a particularly steamy environment. Yet the description of the Nordic sauna was not a mirror image of the Ottoman hammam. While orientalist travellers of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries described the sexual proclivity of Ottoman men and, especially, women, travellers to Scandinavia emphasised the sexual apathy of local sauna goers.

Ogier mused that the “custom and benefit” of the sauna had affected what was considered moral in Sweden. Similarly, the anonymous French manservant commented about the Swedish men that “it is their way” not to see the sexual tension of the sauna. Interestingly, this perspective persisted over time and, if anything, became even more clearly vocalized. The young Italian Guiseppe Acerbi travelled through Sweden in the year 1798-1799 and published his account in London a few years later (1802). At one point, Acerbi was invited to try a sauna by his host Mr Castrein, a chaplain in the parish Kemi in Northern Finland, then a part of Sweden. Acerbi describes his host’s “most exemplary indifference” in submitting to being washed by the female servant. She tended to Mr Castrein first so that Acerbi could learn from his example, but Acerbi describes that when “it came to be my turn to submit, I found myself in a state of extreme embarrassment – and at last I was very glad to get on my clothes, and walk out the bath.”

What we see here is how the travellers to early modern Sweden (including Finland) trod a fine line: providing an exotic account, which highlighted their own adventures, while all the while signalling a distance from the undress and physical proximity between men and women. This required an emphasis on eroticism as changeable between places, and as such, challenges our understanding of the relationship between the exotic and the overtly sexual. In the case of the Nordic sauna, visiting the bathhouse was an exotic and sexualized activity to the travel writer. However, the sexual tension was heightened not by the traveller being lured in, but rather by, to their minds, the lack of erotic tension among the locals.

The travel narratives provide us only with the view of foreign visitors. Outside of the travel accounts – a notoriously biased kind of source, shaped as much by the concerns at home as by the experiences abroad – the picture of the early modern Swedish sauna as a de-eroticized place is more complicated. Sauna going was widespread, but so was the moral commentary on what happened in the sauna. Still, this only reinforces the contested nature of the sauna as a social space where proximity and undress can have changing meanings.

Charlotta Forss is currently an Associate Researcher at the Centre for the Study of the Book, Bodleian Libraries, and Senior Visiting Member at Linacre College, University of Oxford. She completed her PhD at Stockholm University in March 2018. Her research centers on the intersection between cultural history and the history of science, exploring the worldviews of early modern Scandinavians in the context of a European community. This blog post is part of her Swedish Research Council funded research on health and morality in the Swedish sauna, 1600-1800.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com