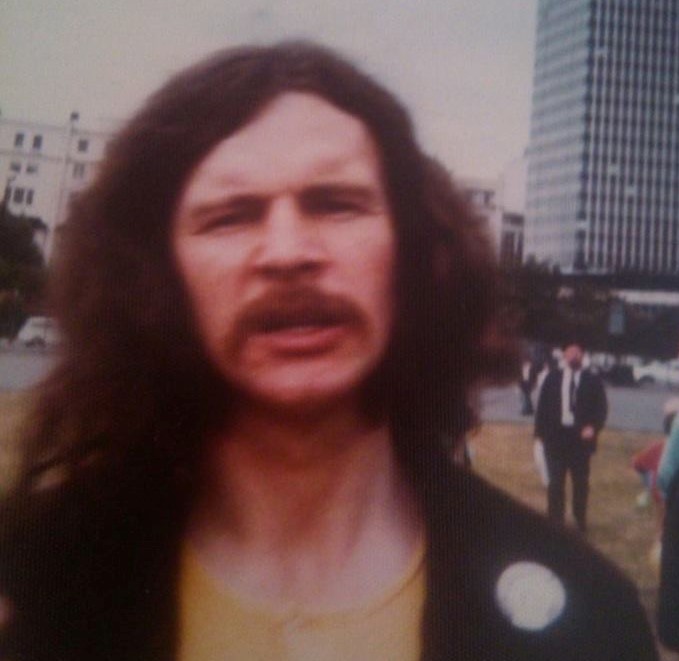

Bob Cant

September 1971 was, in the language of the time, a bit of a gas for me. That’s certainly what I feel when I look at my over-flowing diary for that month.

In the summer of 1971, I went to North America for six weeks. My plan was to divide my time between the USA and Canada but I was rather seduced by New York City and spent much longer there than intended. I had one gay friend, Milton, an artist, when I arrived in Greenwich Village but dozens more by the time I left. It was only two years after the Stonewall riots and, although hardly anyone spoke about politics, these gay men were full of life and self-confidence. And they all had plans! Plans to make a film, plans to travel to California, plans to reduce time looking for sex on the waterfront, plans to open a coffee shop. There seemed to be no limits to their hospitality and I was taken to restaurants and bars and museums and galleries every day. I heard Roberta Flack live in Central Park. Milton took me to Queens to visit his Czech grandmother just so that I could taste her traditional dumplings. I was befriended, desired, embraced, entertained, escorted, guided. I particularly recall being hugged by a tall, sexy Cuban. I was never ignored. It was a full on experience. My diary was full of notes about what I had been doing but there was no space for any reflection.

When I returned to London in September, my diary felt cramped by my attempts to record everything that was going on in my life.

Sex was the big thing. Not just any old sex, but definitely shame-free sex; probably not shameless sex but sex to be enjoyed without question. Most of my time in New York had been spent with other gay men who were living their lives to the full, without any signs of inner embarrassment about their sexuality. I wanted some of that for myself and within twenty four hours of my return to London I was heading off to Earls Court to visit the Coleherne, the only openly gay pub I’d heard of. I had been there once before in a touristy sort of way, to check the lay of the land. I’d been an observer of a world of which I was not a part. This time was different. I was very much part of the action and that must have been what my body language said. That evening, I met someone with whom I had sex; he wanted to see me again but I was more interested in finding a different man. Not necessarily a better man, just someone different.

Two nights later, I met Scott, a blond-ish New Zealander of my age, who swept me away to somewhere rather wonderful for the next three weeks. Sexually, we were very much into each other. That kind of intimacy was completely new for me; it was on a different plane from my previous sexual encounters. He made it clear that he wanted to fuck me and, as I’d never been fucked before, that was a really big deal. Men from Presbyterian Scotland who never talk about sex or about their masculinity do not get fucked easily, unless they’re drunk, and Scott and I did not get drunk together. The time was right for me. Even though I was twenty six, I wasn’t accustomed to thinking about sexual innovation and I was quite slow to come to terms with the possibility of getting what I had wanted for so long. He also took his time to persuade me. He could be said to be a horny opportunist but he also was caring and considerate and patient. He took his time. On 14th September, on our eighth meeting he finally fucked me. Then he fucked me a second time, just to make sure … I saw the world through different eyes. This really was the be-all and end-all. I wanted to remain in that place forever but then he began to tell me something else.

‘You would like Gay Liberation Front meetings – they meet in a hall just near where you live. They’re very political and I know you would enjoy that.’

‘Well, maybe,’ I replied without any enthusiasm. I wasn’t sure if this kind of thing was what I still thought of as ‘real politics’.

‘You’d meet lots of other guys on the same wave length as yourself. I’m sure you’d get a lot out of it.’

He didn’t suggest that this was something we could do together.

I had, of course, heard of GLF but it was mainly something that I associated with New York rather than London. On 21st September, he split up with me; I was upset and rather weepy. But on the 22nd I went to my first GLF meeting. I feel lucky to have met someone who treated me so well while he was ridding me of my virginity. We both got what we wanted and we remained friends in a stoned sort of way.

*******

The GLF meetings take place in the All Saints Church Hall, which is about five minutes away from my flat. I don’t know what to expect but I walk around the building a few times before I venture in. I have been to some very busy, very buzzy places in New York and at first I feel as if I’ve been transported back there. It’s full of young people: most of them are white men and most of them look like the kind of ex-students whom I have mingled with in other settings; some are older; some wear suits as if they had just rushed in from the City. There are very few women.

‘What’s that smell?’ I ask myself. ‘Dope? Patchouli? Unwashedness?’

There’s a lot of long hair and everyone seems to be wearing loose tops which are not quite kaftans and not quite shirts. There are accents from all over the world and I can make out a disembodied Glaswegian sound in the distance. It feels exciting to be surrounded by other men with whom I imagine I might feel at home. It’s gay. I’m gay. This is the Gay Liberation Front.

What’s more difficult to engage with is the fact that there are a large number of men dressed in women’s clothes. Not just any old clothes, but frocks! I had encountered this in New York but so many of them seemed to be acting out dramas from films and TV programmes that I wasn’t familiar with. It was just a spectacle to be viewed. This, perhaps because of the fact that it’s nearer home, is definitely disconcerting. It also strikes me that many of them are wearing clothes that might have been worn by their mothers. I just don’t know what to make of this, but I was told that it was something to do with challenging notions of gender and normality. Growing up in Scotland, I don’t remember seeing any men cross dressing, except in pantomimes, and this is not a pantomime.

There must be several hundred people in the room but it has a different atmosphere from other crowded events that I’ve attended. It’s different from the buzz and the roar of a football match; it’s different from the passivity of a church service; it’s different from the impatience of a political meeting. Perhaps, the nearest equivalent is a rock concert: everyone shares an interest in something that makes them feel positive and they like to believe that there’s a connection between themselves and the performers at the front. There’s one guy, a Canadian I think, who talks a lot and seems to have some kind of leadership role. When he talks, there’s a fair bit of discussion about what he’s saying; no-one tries to shout him down, even when they disagree with him, and quite a lot of people do. He may be a bit of a loudmouth but he’s our loudmouth! It feels as though there’s a lot of trust in that room. I’ve only been here for an hour and already the nerves I was feeling before I walked through the door already feel like ancient history.

I go along to a group for people who have never been to GLF before. There’s a lot of noise and someone is shouting about cottaging (whatever that is) but I just sit there silently. I don’t know if I had expected a nice clear presentation from an expert but that’s not what I am getting. I think that this group, whatever its form, would have gone over my head. But I am sucked into its ambience. This is a critical mass. It’s not a question of learning the rules and norms (if there are any) so much as being one small part of something which is living and breathing and changing all around me.

I hear about smaller groups where you get a chance to share experiences and raise your awareness about the world as it has been, the world as it is now and the world that you aspire to belong to in the future. The whole rationale for coming out. I must find out about how to join one of these groups. This is just what I want for myself. A chance to talk things through with people in the same kind of situation as myself, without any experts telling us what’s right and what’s wrong. It sounds rather hippyish but I’ve known hippies and they haven’t caused any problems in my life. It sounds too as though it could be rather spiritual, with shades of one of the oriental cults. I have heard too that there are consciousness raising groups in the women’s movement. There are all kinds of possibilities but, more than anything else, it feels like a chance to explore what this new life might be all about. There’s a real buzz about GLF and I want to be part of it.

*******

Any grief I was feeling over the departure of Scott was short lived and just a few days later in the Coleherne I met a short blond Californian guy called Ben. We saw each other a few times over the next six weeks but, although he had heard of GLF, he was much less enthusiastic than I was about its potential. I was very excited about the GLF publication, Come Together, but when I showed it to Ben he wasn’t really interested. He shrugged – a friendly shrug but still a shrug.

He had been part of the gay scene, first in the States and then in London. Apart from the Coleherne, I wasn’t really aware of what the scene was. GLF, for me, was a complete new beginning; this was the first place where I had had the opportunity to be honest about my sexuality.

‘Did you ever go to GLF events back in the States? It must have been amazing to have a gay organisation. Breaking new ground.’

‘No. Not really. There had been other organisations like the Mattachine Society that were pushing for law reform long before GLF. I read about them but I guess I’m just not much of a joiner. I’d rather go see a movie.’

As we set off to go to the cinema, I realised that while GLF was something of an earthquake for me it was no more than a slight change in the weather for Ben.

I was just picking up the idea that there were mixed opinions about the gay scene. At the beginning of the month, the only pub I knew was the Coleherne and I had never had a bad time there. But on my first night at GLF I heard someone say that he was pleased to be away from the scene. He wasn’t specific but others in the group nodded their heads in agreement. Despite that, when I heard about the predatory atmosphere of a local pub called the Champion I put aside my political misgivings and made my way there. Nervous as I was, I enjoyed myself and several men were very welcoming. I may have been experiencing what someone at GLF had called Fresh Meat syndrome. There was a discussion at one meeting about organising some kind of happening at the Champion in protest at the hostile way they treated customers who clearly were part of GLF. This was difficult. GLF and the Champion were very different places but it felt OK to be gay in both of them. I couldn’t really see the problem. I was able to be openly gay in more places than I had ever imagined would be possible. Why couldn’t we all get along with each other?

*******

Coming out was one of the key tenets of GLF. There was a slogan that went: Come Out, Come Out Wherever You Are. I was really not ready for that degree of emancipation, particularly in my workplace, but I felt that the honesty at the core of coming out was a good thing. I had just started a new job teaching in a college but I didn’t feel confident enough to come out to my new colleagues. I became more and more intolerant of situations where I felt I had to be dishonest about myself. Only two years previously, I had sometimes used a false name with sexual partners and now I was able to put that behind me. I liked the fact that I was sharing good news about myself. I knew of people older than me who had broken down in tears with friends as they revealed the terrible affliction of their sexuality. I felt that I was talking about the most exciting, the most important thing in my life. In the month of September, I came out to nine people, some of whom I had known for many years, as well as my two more recently acquired flatmates. There was no retching or vomiting or running out of the room screaming; no-one told me not to darken their doors again but that might have been because everyone was the same age as I was (roughly) and we were not in possession of the kind of doors which might have been darkened. No one, including me, was sure about what should happen next. Someone said, kindly, that it would make no difference to our friendship but what did that mean in practice? I think that if I had been able to unveil a boyfriend at that point it would have been well received but if I had told them about cruising around the bars of West London, they might have felt sorry for me and they would certainly not have known what to say.

One friend could only speak about physical acts.

‘Thinking about the way you might be using different parts of your body – doing things that most of us have never even imagined – well, I really don’t know what anyone would think.’

He wasn’t at all hostile; more than anything else, he was just taken by surprise. But he expressed his distaste – or whatever it was – vicariously. I was cool enough at the time and there were no bad vibes between us but, a few hours later, I burst into tears as the impact of what he was saying sunk into my still rather confused consciousness. I felt that he wanted me to explain things more than I had done and, if there was a reason for my tears, it was on account of the pain of feeling that I had to explain the centrality of my being. I often had a delayed reaction to things which I found difficult and this particular conversation had been rather difficult. I am sure he was not the only one who was thinking what he was saying.

I tried to speculate about how I might have responded to someone coming out to me one year previously. I am quite sure that I would not have said that I had had several homosexual experiences which I found it difficult to come to terms with. I might well have fallen back on politeness and at best sympathetic listening. But I would have remained apart from what I was being told and that was exactly what most of my friends were doing with me.

At the very end of the month I came out to Hazel, a woman friend from my university days who was on holiday from her new home in Australia.

‘At last! I’ve known for years and I wondered when you were going to tell me.’ She hugged me enthusiastically. ‘I know loads of gay men and they’re happy about being gay.’ We didn’t go into details about where these happy, gay men were to be found but I gathered they were somewhere in Sydney.

Being a fellow ex-Presbyterian, she was relieved that I was breaking away from the burden of Presbyterian guilt.

The others were all rather more cautious. None of them mentioned other gay people whom they knew: no unmarried aunties, no work colleagues, no old school friends, nobody at all. It was clear that most of them felt at a loss about what to say. It was a strange experience. I had heard about people whose coming out stories had generated responses about the ancient Greeks but at least I was spared that. All my friends seemed happy to go on meeting up with me and one of them asked me to be the best man at his wedding later that year. Coming Out was, for me, an important social and public experience but for them it was more a matter of a secret being shared and respected.

I was cautious myself in terms of the way that I recorded these coming out experiences in my diary. The term, coming out, did not appear there but the word, confession, did. Presbyterians don’t do confessions and so the term did not have the same resonance that it would have done in the diary of a Catholic or ex-Catholic. I was not being as open in my diary as I was in my conversations with my friends. Much more coded. I don’t think this was because I feared that my diary would be seized and read by some kind of morality police. Much more likely that it reflected an ongoing sense of uncertainty about my openness about my sexuality. One year previously I had not come out to anyone although I had had sexual experiences with several men. The word, confessions, was a reflection of the fact that while I was happy about the process I was going through there was still an aftermath of guilt or fear of being exposed lurking somewhere under the surface.

This piece is an extract from Bob’s upcoming memoir focused on the period 1967-1981. The named individuals have been given pseudonyms.

Bob Cant has been a teacher, a trade unionist, a community development worker, a Haringey activist and an editor of several collections of LGBT oral history. He now lives in Brighton and his first novel, Something Chronic, was published in 2013. Bob tweets from @bobchronic

Bob Cant has been a teacher, a trade unionist, a community development worker, a Haringey activist and an editor of several collections of LGBT oral history. He now lives in Brighton and his first novel, Something Chronic, was published in 2013. Bob tweets from @bobchronic

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com

What a beautiful clear memory you have of who you were during those amazing coming out times. Your joy and explorations are all mixed together with the sense of a new exciting world — of politics andpossibilities, of pleasures, of freedom, body and soul. Thanks for these remembered breaths of the new spirit of play, sex and pride that ignited a new generation…..Oh Bob, keep on writing.

Thanks so much for this piece which I read with much enthusiasm. I love the depth of details you remember from that marvellous summer you had in NYC and later London – helped by that diary you wrote and kept for 50 years! Your descriptions and dialogue are wonderful and so evocative of those times. As you know, although it was in another country, my coming out also took place in the Summer of 71, so we share that and much more!

Dear Bob

Was I one of the 9 people you first came out to?

I left for Canada with Bill late summer 1971. You wrote to me there and told me about your time in New York and that you had ‘come out’ as gay. It is possible I’d never heard of the term ‘ come out’ before your letter. I can remember being rather pleased at the news – it somehow seemed to be a brave , progressive, revolutionary kind of act which I approved of. I can also remember feeling envious of you being in New York and free while I was in the process of embarking upon married life. I cannot remember of I replied to you ( is that correct?) or if I did what I said and I feel really sorry about that now.

I think this is a terrific piece . You’ve captured the atmosphere of the times and you paint a clear , cool and fascinating picture of yourself in the middle of it all. Really looking forward to further episodes .