One of the biggest challenges facing medieval historians, and perhaps especially historians of medieval sexuality, is interpreting the actions of individuals at a remove of several centuries. Take, for example, the case of King Richard I of England, who has sometimes been considered something of a gay icon. The main evidence for Richard’s homosexuality comes from the chronicle of Roger of Howden, who recorded that:

Richard…remained with Philip, the king of France, who so honoured him that for a long time they ate every day at the same table and from the same dish, and at night their beds did not separate them. The king of France loved Richard as his own soul, and they loved each other so much that the king of England was absolutely astonished.

For many modern readers, the fact that the two men shared a bed can mean only one thing: they were having a sexual relationship. But, as historians such as John Gillingham and Stephen Jaeger have pointed out, such an interpretation rests heavily on the projection of modern practices and perceptions onto the distant past. For high-status medieval men, sharing a meal and a bed had more to do with politics than sex, and the same was true of other intimate gestures such as kissing and handholding. Such behaviours served as tokens of peace or reconciliation, and as demonstrations of alliance and favour. So when Henry II learnt of his son’s attachment to the French king, he was shocked not because he thought Richard was homosexual, but because he had formed an alliance with his father’s worst enemy.

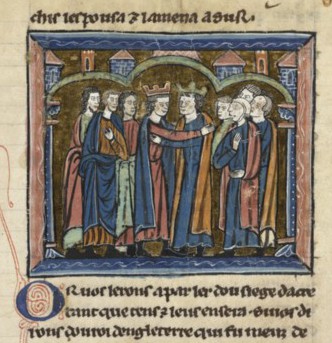

The gulf between medieval and modern views of bed-sharing becomes even clearer if we consider some medieval depictions of the Magi. According to St Matthew’s Gospel, three wise men from the East came to visit the infant Jesus at Bethlehem. On their journey, they encountered Herod. He asked that, once they had found the child, they should tell him of its whereabouts, for he too wanted to worship Jesus. But God warned the wise men in a dream that they should not return to Herod. The Dream of the Magi became a popular image during the later middle ages, and was depicted in a variety of settings, from psalters to stained glass windows, sculptures and wall-paintings.

From a modern perspective, two things are remarkable about such images. The first is that, even when sleeping, the trio (who have by now become kings) wear their crowns. The second, more striking, feature of these depictions is that the trio are always to be found to be sharing a single bed; in some images they even appear to be naked – except, of course, for the crowns which indicate their exalted social status. Given that these are revered figures with a place at the heart of one of the most important stories in the Christian tradition, it seems unlikely that medieval illustrators were trying to suggest that the Three Wise Men were engaged in some form of ménage à trois.

That the Magi could be widely depicted in what the modern eye can view only as an extremely compromising position surely reflects a significant shift in attitudes to bedsharing between the middle ages and the modern day. This shift has significant implications for our understanding of the sexuality of Richard I – and indeed for our wider understanding of medieval sexualities and behaviours.

Katherine Harvey is an Associate Lecturer at Birkbeck College, University of London where her research focuses on the pre-Reformation English episcopate. Her first book, Episcopal Appointments in England c.1214-1344, was published by Ashgate in January 2014. Katherine’s current project combines ecclesiastical history with the history of gender, sexuality and medicine. She tweets from @keharvey2013

Katherine Harvey is an Associate Lecturer at Birkbeck College, University of London where her research focuses on the pre-Reformation English episcopate. Her first book, Episcopal Appointments in England c.1214-1344, was published by Ashgate in January 2014. Katherine’s current project combines ecclesiastical history with the history of gender, sexuality and medicine. She tweets from @keharvey2013

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com

Just a small correction in the interest of accuracy: St. Matthew’s Gospel does not in fact claim three wise-men came to visit the infant Jesus. It simply indicates that wise-men came. It’s rather the tradition of the Church that says that three wise-men visited; undoubtedly because there were three (theologically significant) gifts presented. Not that it changes the substance of your article, but I thought you’d like to know. And btw: a very interesting read indeed!

There is/was also a tradition in Scotland, especially in the Highlands, of men ‘following the communion seasons’ sharing a bed. One bed in a manse in North Uist was big enough to sleep three or four men.

Pingback: Three Wise Men in a Bed: Bedsharing and Sexuality in Medieval Europe | My BlogThe Philosopher's blog.

Um, people of both sexes shared beds because rooms and beds were a rare commodity, it was share a bed or sleep on the dirt floor. That was the norm until Saint Marriott started building his manors across the world and people could final have a room and a bed all to themselves.

There’s an interesting counterpoint to this in the story of the cross-dressing abbot from Bocaccio’s Decameron (day two, third story).

The Inn is full, so Alessandro has crept into a bin in the abbot’s room to sleep:

> The abbot, who slept not, nay, whose thoughts were ardently occupied with his new desires, heard what passed between Alessandro and the host and noted where the former laid himself to sleep, and well pleased with this, began to say in himself, ‘God hath sent an occasion unto my desires; an I take it not, it may be long ere the like recur to me.’ Accordingly, being altogether resolved to take the opportunity and him seeing all was quiet in the inn, he called to Alessandro in a low voice and bade him come couch with him. Alessandro, after many excuses, put off his clothes and laid himself beside the abbot, who put his hand on his breast and fell to touching him no otherwise than amorous damsels use to do with their lovers

The abbot is actually a woman, but Alessandro does not know this. I wonder why Alessandro put off his clothes to go to the abbot? If it was his habit to sleep nude, why did he still have his clothes on.

I am not sure what to make of this, and would be interested to hear your thoughts.

Pingback: Three Wise Men in a Bed: Bedsharing and Sexuality in Medieval Europe

“and at night their beds did not separate them. The king of France loved Richard as his own soul, and they loved each other so much that the king of England was absolutely astonished.“

I don’t think they were gay because they slept in the same bed – I think they were gay because obviously they were in love. That quote describes what we now understand as being in love

Pingback: The lost ancient practice of communal sleep – She Emerge Global Magazine