The typical Valentine’s Day menu highlights aphrodisiac foods, suggesting that it is a day to celebrate lust as much as love. To this end, I offer you an introduction to one of the sex symbols of the eighteenth century: the castrato.

Eighteenth-century Europeans had known about eunuchs for years. There were numerous historical examples, as well as more exotic ones from China and the Ottoman Empire, but the numbers of castrati in the West had been growing since the sixteenth century. Their soprano (and, importantly, non-female) voices were usefule in Catholic church choirs throughout the Holy Roman Empire. From the seventeenth century, the popularity of opera, with its use of castrati singers, allowed more people than ever to see them in person. An estimated 4000 boys, sent by their parents for testicular removal before their voices broke, flooded early eighteenth-century Naples for conservatory training.

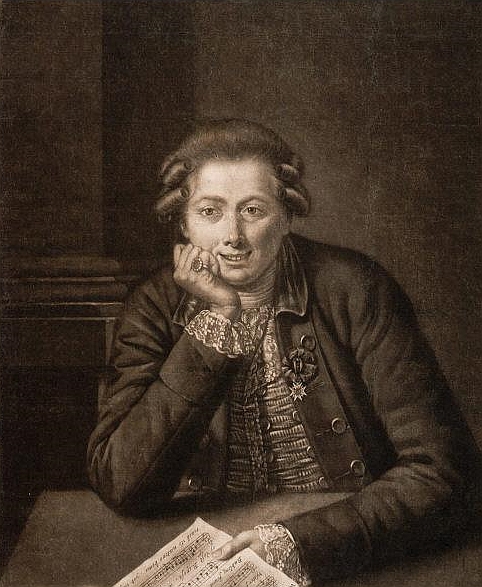

Successful castrati were treated like modern day superstars and could command extremely high fees. The title page of Charles Ancillon’s Eunuchism Display’d (1718) noted that the book was “Occasion’d by a young Lady’s falling in love with Nicolini, who sung in the opera at Hay Market and to whom she had like to Have been Married”. Their popularity showed no sign of waning by 1780 when satirist Edward Beetham commented that “through the charm of sound, [Giusto Tenducci] has as many admirers as the first actors, and particularly among the female world, by which he has been almost deified”.

But castrati were also ridiculed for their unusually long limbs, wide chests, hairless skin and lack of testicles. So what was the appeal?

Eunuchs had long been associated with sensuality, being guards for (what Westerners perceived as) the sexually-charged harems of the Ottoman Empire. They were hyper-sexual and charming to both sexes, being neither fully male nor female. Like women, castrati were driven by their bodily desires; but being not-quite-male, they were easily controlled by women.

Surgeon John Marten argued in 1711 that eunuchs would destabilize marriage by “defiling the Nuptial Beds of others” through their lack of self-control: “’Tis said that Eunuchs love Women passionately, and being of weaker Mind after than before Gelding, are the more susceptible to this passion”. Beetham further explained that these “mutilated fellows” were perfect companions for women, “adapted to gratify the inordinate craving of those rank beldams”. In addition to providing care-free sex without pregnancy, the castrati would “never decline the encounter till they have the word of command”.

Such concerns were underscored in 1766 when Dorothea Maunsell eloped with Tenducci. (Marriage to eunuchs was illegal in Catholic areas, but not in Britain’s territories.) Tenducci was a questionable husband in many ways, ranging from his lack of manhood to his foreign status, but worst of all, he had lured her away from her family and undermined her father’s role as household head. Order was only restored when the marriage was annulled eight years later on the grounds of Tenducci’s impotence.

The castrato could also seduce men, as Casanova found when he met Bellino in 1744. From the outset, Casanova was convinced that everything about Bellino “betrayed a beautiful woman, for his dress concealed but imperfectly the most splendid bosom”. He attempted to seduce Bellino, “by going straight to the spot where the mystery could be solved”, only to encounter “a very strong resistance”. Casanova sent the castrato away, finding himself “disgusted, confused, and almost blushing”. Bellino insisted that uncovering the truth would not help: “for you are in love with me independently of my sex, and the certainty you would acquire would make you furious”. Casanova finally persuaded Bellino into bed, revealing that the ‘castrato’ was actually Teresa Lanti Palesi.

We can’t take Casanova’s account as fact. However, his emphasis on the sexual ambiguity of the castrato was clearly intended to titillate, while the revelation that the object of desire was female would provide a <cough> comfortable resolution.

The castrati, with their lack of clearly defined sex, did not fit comfortably within the hierarchy of early modern Europe. But that very ambiguity, in turn, made for sexual curiosity, with books like Ancillon’s and Casanova’s offering the chance to lift the skirts (or peer into the trousers) of the famed castrati.

Lisa Smith is an Associate Professor of History at the University of Saskatchewan. Her interests are gender, family and health, pain, fertility, leaky bodies, and recipes. At the moment, she is finishing a book on Domestic Medicine: Gender, Health and the Household in Eighteenth Century England and France. She blogs at The Sloane Letters Blog, contributes to Wonders and Marvels and co-edits The Recipes Project. Lisa tweets from @historybeagle

Lisa Smith is an Associate Professor of History at the University of Saskatchewan. Her interests are gender, family and health, pain, fertility, leaky bodies, and recipes. At the moment, she is finishing a book on Domestic Medicine: Gender, Health and the Household in Eighteenth Century England and France. She blogs at The Sloane Letters Blog, contributes to Wonders and Marvels and co-edits The Recipes Project. Lisa tweets from @historybeagle

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com

Pingback: Radical Books: Trans Like Me (2017), CN Lester – History Workshop