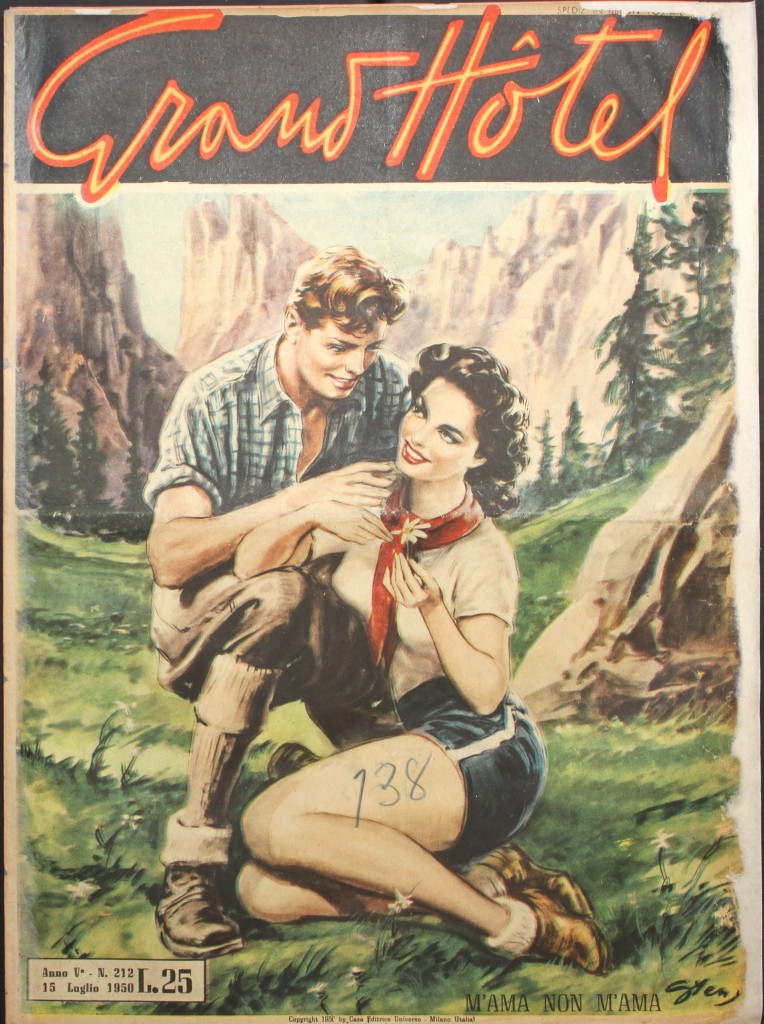

In July 1955 Wanda Bontà, agony aunt for the popular Italian magazine Grand Hotel, received a letter that she was both amused and baffled by, if the response she published in her column is anything to go by. It was written by a young woman who sought advice on her love life as she was unable to choose between two men; a reliable and financially secure goldsmith or the penniless labourer whom she loved and ‘couldn’t live without’. Wanda advised her to choose ‘the labourer, naturally, since you can’t live without seeing him. Or do you want to choose the goldsmith and die?’

The decision seemed perfectly obvious to Wanda as it does to me, reading these 1950s sources from my twenty-first-century perspective. However, it clearly wasn’t obvious to the young woman who wrote the letter. This simple letter exchange snatched from a magazine ‘problem page’ points in its own small way to how understandings of romantic love and its place in courtship and marriage have meant very different things to different people over time.

Of course the fact that people didn’t always marry for love or that two lovers might face obstacles to being together is not any surprise; it’s a notion as familiar to readers of Jane Austen as it is to historians of courtship. However, what I’ve come to realise in my research on love and marriage in post-war Italy is that there is rarely a clear-cut distinction between marriage for love and marriages of convenience or arranged marriages. The fact that the 1955 letter-writer experiences her dilemma so sharply is actually fairly unusual. More often, considerations of romantic love, sexual attraction, economic prospects, class and family interest were present in varying degrees in people’s decisions to marry.

A lot of my research lately has involved reading through the diaries and memoirs of Italian men and women, and trying to trace the changing vocabularies and experiences of courtship from the end of the war up to the 1960s. As always, looking at personal narratives confounds any simple story of the history of romantic love; here men and women who entered what I would describe as marriages arranged or heavily encouraged by their families often describe deep feelings of love, while often people who met their partner at a dance or at university and married freely were just as likely to describe feelings of indifference towards their partner. The real question, it seems to me now, is not whether people in a certain place and time married for love or not, but what they understood by love; what it meant in the context of their society, their own circumstances and their personal understanding of the world.

What I’ve found so far is that women who married in the early 1950s, often prompted by their families to marry young, were also likely to describe strong feelings of love for their husbands. One woman described her fear of marriage and her delaying tactics on the wedding day but was careful to point out repeatedly that this was ‘despite’ her deep love for her husband. In contrast, those who married in the 1960s were more likely to marry out of choice, but also to feel indifference rather than love before the wedding.

What might any of this mean to historians of courtship and romantic love? I’m still making sense of it myself, but it does seem as if the changing cultural climate of the late 1950s and 1960s Italy was having an impact on people’s choices and experiences, though not in the ways one might first think. For the women who married in the early 1950s, love, family and obligation were clearly bound up together. The women who married in the 1960s were perhaps coming of age in a different world, more connected to cities and to broader Western ideals; armed with heightened expectations of romantic love, they perhaps viewed their own choices differently.

Romantic love will always be a subjective experience that can never be fully described to another person, let alone a historian trying to reconstruct these experiences in the past. I’m no closer really to knowing how people felt in post-war Italy. However, by catching glimpses of the changing ways in which people described their experiences over time, I can catch glimpses of what people might have meant when they spoke about love, at different moments in time.

Niamh Cullen is an Irish Research Council CARA Marie Curie fellow at University College Dublin. She is currently researching histories of courtship and love in post-war Italy and is also broadly interested in gender, emotions and the body in contemporary European and Mediterranean history. Niamh tweets from @niamhanncullen

Niamh Cullen is an Irish Research Council CARA Marie Curie fellow at University College Dublin. She is currently researching histories of courtship and love in post-war Italy and is also broadly interested in gender, emotions and the body in contemporary European and Mediterranean history. Niamh tweets from @niamhanncullen

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com

Pingback: What’s Amore? Courtship and marriage in post-war Italy | Niamh Cullen