In 2012, the FDA approved Truvada, a popular antiretroviral drug, for use by HIV-negative people to prevent infection. The use of Truvada for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis, or PrEP, has been controversial. Veteran AIDS activist Larry Kramer has called HIV-negative gay men who elect to take the drug “cowardly.” Some gay men on PrEP have pushed back against such criticism by reclaiming the slur “Truvada whore.” This debate harkens back to conflicts within the gay community during the early days of the AIDS epidemic when gay men argued over how to reconcile the sexual openness of the 1970s with the growing danger of a deadly disease that appeared to be linked to gay men’s sexual practices.

Although AIDS did not signal the end of sexual liberation, the epidemic did change the meaning of sex for many gay men, mixing potent feelings of fear with otherwise pleasurable acts. In Tim Murphy’s recent piece on PrEP for New York Magazine, Sarit Gloub, a psychology professor at Hunter College, described her research findings that half of gay men think about HIV most or all of the time during sex. This fear is in part a result of the very “sex-positive” programs that gay men’s groups developed in the 1980s, which eroticized safer sex for gay men but also represented sexual contact between men as dangerous.

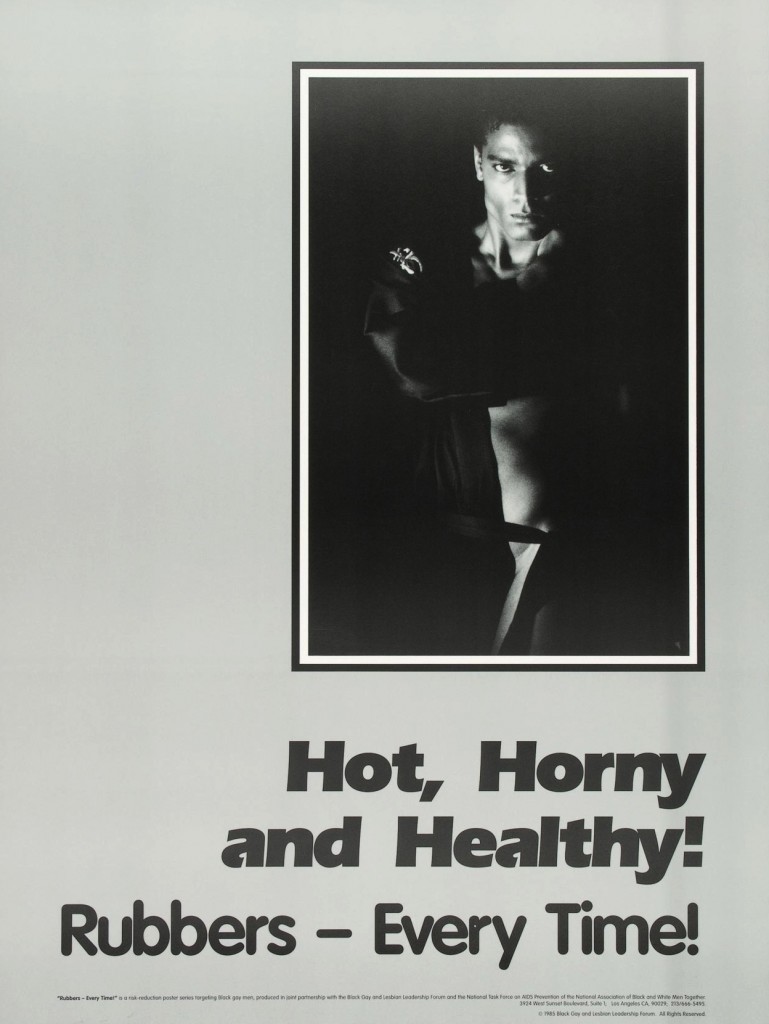

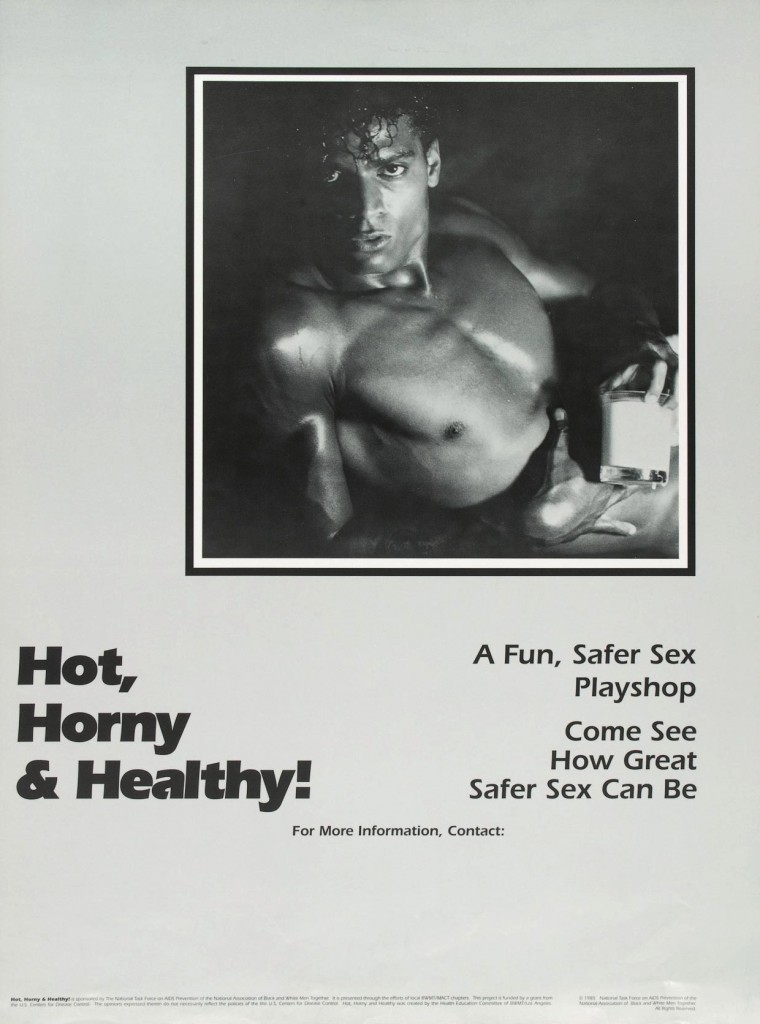

Beginning in the late 1980s, the National Task Force on AIDS Prevention, an interracial AIDS service organization, began to offer safer sex “playshops” with names like Hot, Horny and Healthy and Safer Sex: Hot & Healthy to gay men of color. Participants began by discussing sexual grief—what they missed most about sex in the time before AIDS. They then discussed “extremely erotic but safer ways of touching or being touched.” Participants used dildos to practice applying condoms, ranked a variety of sexual practices in order of HIV transmission risk, from “mutual masturbation” to “getting fucked without a condom.” At the end of the session, facilitators were to remind participants “that they don’t need to fear AIDS or sex, but Safer Sex does mean a commitment all the time, not just some of the time, or even most of the time, but all [of] the time!” (italics in original) [1] The playshop facilitator acquainted gay men with new ways of pursuing sexual pleasure, but at the same time the call for constant vigilance constructed that pleasure as a threat.

By the late 1980s AIDS educators were concerned about “relapse” among gay men who had started practicing safer sex in the first decade of the AIDS epidemic. In this context, the black gay men’s group Gay Men of African Descent incorporated messages about safer sex relapse into Party, a thirty-minute safer sex education video they produced in 1992. Throughout the video, a group of black gay men at the titular party discuss how they have adapted their sex lives to the reality of AIDS, and offer one another advice. At the beginning of Party, a character named Aaron shows up at his friend Paul’s apartment, completely distraught. He’s just been in the park, where he had unprotected sex with a stranger. He’s distressed not only because he risked exposure to HIV, but because safer sex has become an important part of his social identity. He tells Paul, “[T]he thing that really gets me is that I knew better. I’m the one who’s always preaching to you guys about safer sex.” Later in the video, another character, Kofi, leaves the party in a huff after his friends admonish him for a “reckless” sexual liaison. Paul catches up to him to say, “If it seems that everyone was coming down on you in there… it’s just that we care about you and we want you to be safe…. Aren’t you always preaching that black men should support each other, watch each other’s back? That’s all we’re trying to do. We’ve got to help each other stay strong.” [2] Since individual behavior change would weaken over time, as it had for Aaron, Party reframed the commitment to safer sex as a communitarian enterprise.

Even as AIDS activists have criticized fear-based HIV prevention messages, sex-positive programs such as Hot, Horny and Healthy and Party stoked gay men’s sense of fear and danger around their own sexuality. When they designed these programs in the 1980s and early 1990s, gay AIDS educators well imagined that effective HIV treatments might never come. In order to survive, gay men would have to find pleasurable ways to have safer sex, and to encourage one another to do the same. Sex-positive programs may have heightened gay men’s feelings of fear about their sex lives, but even as the AIDS crisis fed a turn toward sexual moralism in some circles, these programs did not simply yoke gay sexuality to a respectability politics of monogamy, marriage, and military service. Hot, Horny and Healthy and Party recognized the importance of pleasure in HIV prevention, honored gay men’s attachment to the “lost” sexual golden age, and maintained that gay men could find the resolve to maintain their commitment to safer sex not only as individual sexual citizens, but through the ties of racial and ethnic community. Attending to gay men’s changing understanding of sexual pleasure throughout the AIDS epidemic places Truvada within a longer queer history of ambivalence about sexual liberation. At the same time, it points to the contingency of gay men’s feelings about their own sex lives in the age of AIDS.

[1] National Task Force on AIDS Prevention, “Safer Sex: Hot & Healthy Facilitator’s Manual,” n.d., Box 2, Folder 46, National Task Force on AIDS Prevention Records, UCSF Special Collections.

[2] Alan Sharpe, Party script, 1992, Box 10, Folder 9, Gay Men of African Descent Records, Schomburg Center, New York Public Library.

Dan Royles is a visiting assistant professor of history at Richard Stockton College of New Jersey. His research focuses on the politics of the body and social movements in recent American history. He is currently working on a book manuscript, oral history project, and digital archive dealing with the political culture of African American AIDS activism. Follow him on Twitter @danroyles.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com

Reblogged this on Denal's Mind and commented:

So that others will know