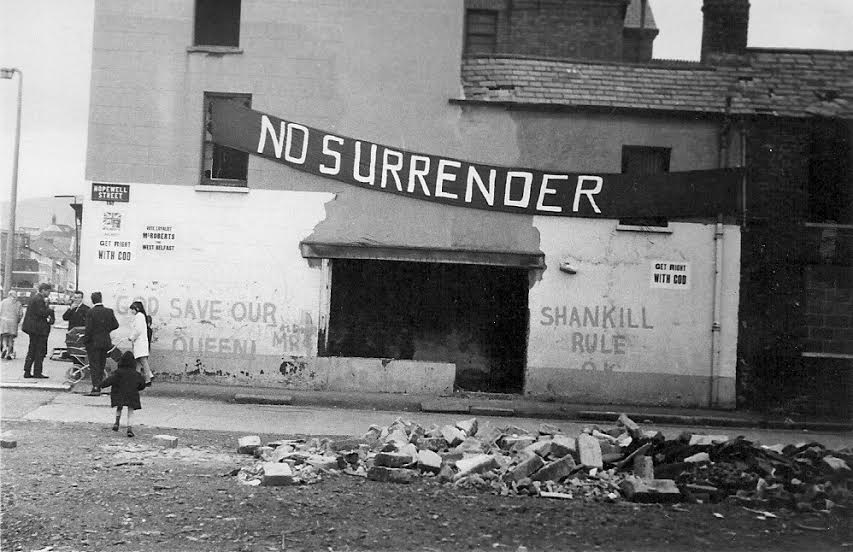

The death of Rev. Ian Paisley has been occasion for reflection upon the United Kingdom’s most firebrand, and certainly one of the most memorable and divisive, political figures in modern times. Paisley rightly will be remembered for his hardline and extreme unionist stance throughout his political and religious career. Northern Ireland’s society and politics have been synonymous with deep and bitter religiously orientated sectarianism, violence, conflict, militarism, and seemingly intractable community divisions since the late 1960s. And Paisley was the most vocal and most recognisable protagonist of its continued community divide. But the intractable oppositions within Northern Ireland appeared to come together in remarkable unanimity on one particular issue, which Paisley almost made his own: that of the reprehensibility of male homosexuality, and questions of sexual minorities in general.

The Northern Ireland parliament stoutly resisted any attempt to impose the Sexual Offences Act of 1967, which had partially decriminalised male homosexuality in England and Wales. Even after the imposition of direct rule and the ending of devolved government in 1972, any attempt by the Northern Ireland Office to introduce partial decriminalization was met with voluble and intense opposition. A high profile case, brought to the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR), Dudgeon vs. the United Kingdom, forced the UK government eventually to impose the partial decriminalisation of male homosexuality in Northern Ireland in 1982. It was a landmark ECHR case: the first to be decided in favour of LGBT rights. It has formed the basis in European law for all member states, in particular new states joining the EU ever since.

Opposition to the decriminalisation of male homosexuality appealed to many across the community divide. However, the impetus to maintain gay sex as criminal was provided by the evangelically inspired and highly popular ‘Save Ulster from Sodomy!’ campaign. The ‘Save Ulster from Sodomy!’ campaign was started in the mid-1970s by the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) and headed by its political and religious leader, Ian Paisley. The DUP started its campaign in response to the formation of the Northern Ireland Gay Rights Association (NIGRA) in 1975, and also to its mistrust of the Northern Ireland Office and the British Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, who had the absolute power to make law in Northern Ireland by orders in council. The fear was that decriminalisation of male homosexual acts would be imposed by left-wing Labour Secretaries of State for Northern Ireland, under pressure from gay rights lobbying groups in Great Britain and in Northern Ireland.

It was a concerted and persistent campaign, which advertised itself in the newspapers, and demonstrations and pamphleteering on street corners; it promoted itself as a religious crusade, and lasted for many years, though the height of its activity and prominence was between the mid 1970s and 1982. In Paisley’s world-view, Ulster, the hallowed province, had to be made fit for the second coming of Christ, and therefore needed ‘saving’ from sodomy. In a society riven by male-dominated violence and religious conflict, LGBT people at the very least would be wary about exploring their sexuality, and certainly emotions of guilt shaped and directed their lives, freedom of action and sense of agency. A recent study by geographers demonstrates that sectarian endogamy, the norm in Northern Ireland, is replicated in lesbian and gay coupling in the province. For most Northern Irish LGBT people, the only way to lead ‘out’, normal lives, has long been to leave Northern Ireland.

It is remarkable the extent to which the Roman Catholic hierarchy gave its tacit support to this campaign, and the ways in which paramilitary organisations on both sides of the divide regarded LBGT people as ‘natural betrayers’ in their midst. Religion and sectarianism, more than any other phenomena, shaped the sexualities and lives of LGBT people in Northern Ireland until the peace process of the late 1990s. Paisley’s contribution to the continuing homophobia in Northern Ireland is considerable. Unlike the rest of the United Kingdom, the DUP-dominated Stormont parliament has vetoed the gay marriage bill multiple times, and evangelically motivated politicians feel free to make homophobic comments on a regular basis. Northern Ireland’s society is unique in the context of Western Europe in the intensity and the extent of its homophobic attitudes. In a huge research project into bigotry in Western countries conducted in 2007, out of the 23 countries surveyed, Northern Ireland was the most homophobic country surveyed, topping the list along with Greece. Paisley’s legacy for the Northern Irish sectarian conflict is hugely complicated in itself. But his broader impact on Northern Ireland’s society – and its quality of civil society – also endures.

Sean Brady is a Lecturer at Birkbeck, University of London. He is the author of Masculinity and Male Homosexuality in Britain, 1861 – 1913 and has recently edited a critical source edition on John Addington Symonds (1840-1893) and Homosexuality. His current research examines religion and sectarianism in relation to masculinities in Northern Ireland after 1921, and he is working on a book, Northern Ireland: A Gendered History. He tweets from @bradybirkbeck

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com

Great article Mr. Brady. I wasn’t aware of this man Ian Paisley until now, I’m always glad to find more references to misinterpretations of the Bible. I think we both would say the story of Sodom and Gomorrah is about hospitality not homo-sexuality, but have you ever heard the Pauline argument, which explains how Paul deviated the Bible from Jesus’ teachings to Roman sympathy and fear of his own homosexuality and sexuality in general?

Pingback: Jim Wells health committee call over gay abuse comments - Northern Ireland Gay Rights Association

Pingback: What Ireland’s Same-Sex Marriage Vote Means for Northern Ireland - Northern Ireland Gay Rights Association