I have recently been pondering Voltaire’s much quoted but rarely contextualized observation that ‘historians are gossips who tease the dead’.

It goes to the heart of something that’s been bothering me ever since I dug further into the details of a case of a young woman who had appeared in my book as a victim of trafficking. I used her story of being procured in Wellington, New Zealand, to work in the casinos of Buenos Aires and later (briefly) the streets of London to illustrate some of my points about the UK’s approach to trafficking cases, the experiences of migrant sex workers, and the role of ‘repatriation’.

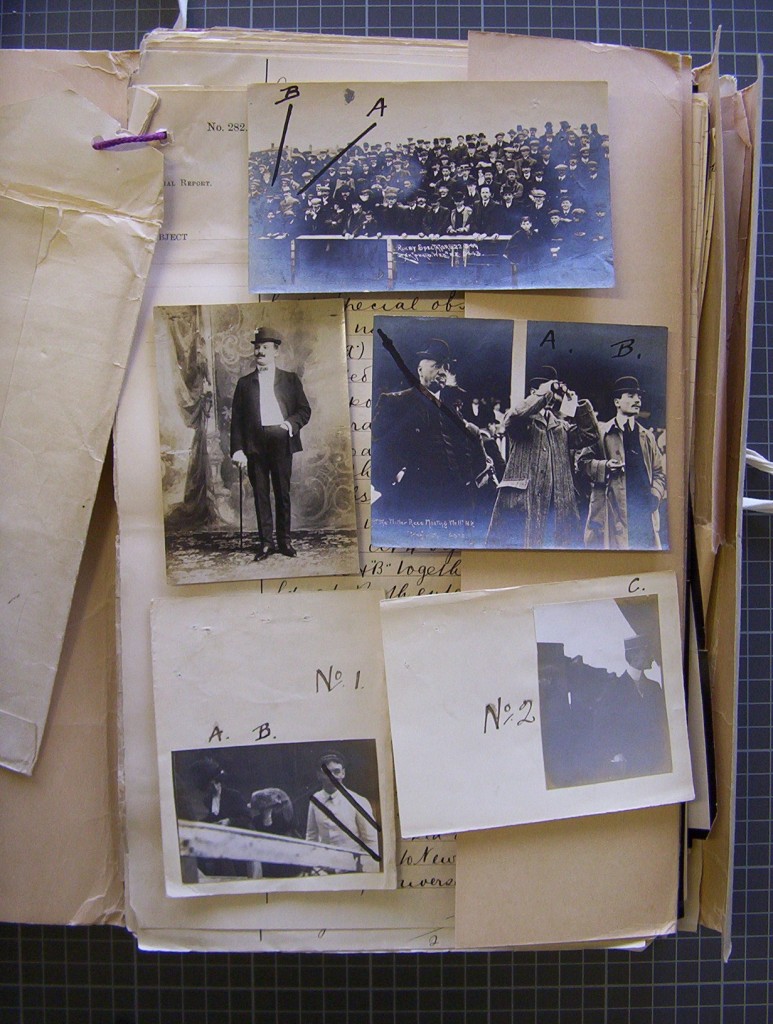

I encountered many small fragments of similar stories in my earlier research, but hers is the one I cannot get out of my head. As part of my new project, I resolved to delve more deeply into her story and tease out more details of her life, and the lives of her traffickers. In the files, she appeared under her real name, Lydia H—–, but initially she had been identified as ‘Doris Williams’. I had assumed this was because a pseudonym had been given her by her traffickers to make her more difficult to trace. But it was while doing further research in New Zealand historical newspapers that I realised that she had in all likelihood requested this pseudonym herself, in order to protect her identity. In my keeness to tell her story–or perhaps mobilize her story to make a point — I had outed her.

I was a gossip, teasing the dead.

Historians ‘out’ their subjects, they tease the dead, all the time of course, but we assume that once a file is opened from the usual archival closure this isn’t an ethical issue. When Lydia H—–’s name appeared in my book, she had been trafficked over a hundred years before, and had almost certainly been dead for at least 20 and probably more like 40 years. But it has made me think about the way I have used women’s complicated and nuanced stories to say something about my own research subject, prostitution.

Even as I, and many other feminist historians, insist that women who sold sex held myriad identities aside from their assigned identity of ‘common prostitute’, they nonetheless appear in much of our work as, in fact, prostitutes. We separate them from other working women, and we divorce their experiences of sexual labour from the rest of their lives. When I wrote about Lydia H—–, even to illustrate the uniqueness of her experience, I still situated her in the midst of the sexual scandal and trial of which she was a part.

I mentioned that she had been a photographer’s assistant in passing, as though the two or so years she had spent at this job didn’t matter as much as her six months as a prostitute. Once she disappeared from the police file I was working with, I simply let her go. In trying to contextualize prostitution, I actually removed her from the full and complicated social and economic context of her own life.

Decontextualizing people also allows us to import our own politics and opinions into their incomplete lives. In my open-mindedness about commercial sex and sexuality more generally, I forgot, for a moment at least, that some women who experienced it in the past were ashamed. And they have as much right to that shame as other people have to pride. We must be very careful not to tease them.

Julia Laite is a lecturer in modern British history at Birkbeck, University of London. She is interested in the history of women, gender, sexuality, crime, migration, prostitution, and occasionally lorries. Her first book, Common Prostitutes and Ordinary Citizens: Commercial Sex in London, 1885-1960 was published with Palgrave Macmillan in 2011. She is currently working on trafficking and women’s migration in the early twentieth century world.

Julia Laite is a lecturer in modern British history at Birkbeck, University of London. She is interested in the history of women, gender, sexuality, crime, migration, prostitution, and occasionally lorries. Her first book, Common Prostitutes and Ordinary Citizens: Commercial Sex in London, 1885-1960 was published with Palgrave Macmillan in 2011. She is currently working on trafficking and women’s migration in the early twentieth century world.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com

Thoughtful, and thought-provoking. Thank you for writing this.

I often refer to myself as a gossip columnist of the Rwandan royal family, because I write about all their marriages and sex lives, and internal intimate politics. I’m half-joking, but really, that’s a lot of the job. The sources I consult are also sort of paparazzi-like, which I think supports how I use them.

This was a very thought-provoking piece.