Sometimes the queer stars align right when it’s needed most. Philadelphia has spent the past few decades effectively cultivating an LGBT-friendly reputation, as witnessed in last year’s groundbreaking trans-affirmative city ordinance. But a recent, vicious gaybashing incident in Center City, not to mention Pennsylvania’s unfortunate precedent as the first state (singular until very recently) where same-sex marriage is perversely recognized under law and yet can lead to one’s firing through still-legal discrimination, have reminded us of the ongoing injustices in a moment already being inscribed as triumphant. It’s a crucial moment to think critically about historical narratives, and who better to lead the discussion than Marc Stein?

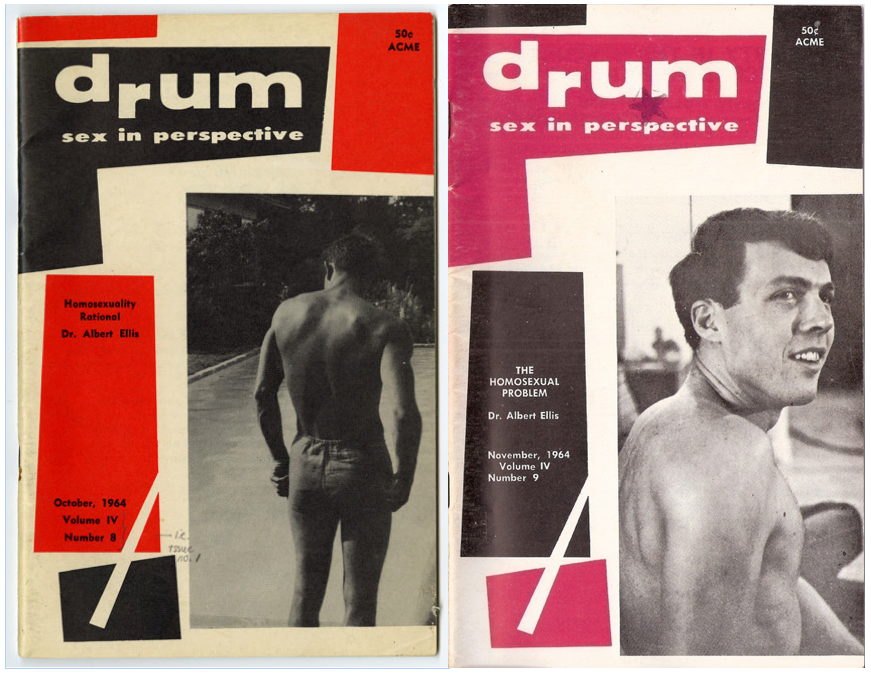

Stein, whose City of Sisterly and Brotherly Loves: Lesbian and Gay Philadelphia, 1945-1972, first published in 2000, remains not only the definitive queer study of the Quaker City but an exemplar of LGBT communities studies period, was at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania on October 2, 2014 to discuss “Canonizing Homophile Sexual Respectability: Archives, History, and Memory.” The timing was made even better by adjacent co-sponsor Library Company of Philadelphia, who hosted a pre-lecture reception to celebrate the closing of their fantastic That’s So Gay: Outing Early America exhibition, which set record attendance numbers. While that project looked nationally, Stein focused locally. To pull his expansive theme into focus, Stein used the magazine Drum, published in Philly by gay activist Clark Polak between 1964 and 1967.

As Stein showed in City of Sisterly and Brotherly Loves, Drum advanced a vision gay culture defiantly at odds with prevailing homophile norms. Groups such as the Mattachine Society and Daughters of Bilitis had long advocated a respectability politics that privileged assimilation and normalcy, to counter the pernicious stereotypes about queer people disseminated by the government, psychiatry, and the mass media. Part of that framework entailed downplaying sex and sexuality for a buttoned-up professionalism. Polak countered that by celebrating sex, indeed breaking new ground when Drum began publishing full-frontal nudes in 1965. Showing nude men was something neither the homophile press nor physique magazines would venture to do at the time, for fear of both disrepute and obscenity charges (a well-founded concern, as witnessed by earlier charges against physique publishers Bob Mizer, Al Urban, and a slew of others). Polak’s embrace of “prurience” led to the expulsion of his Janus Society from ECHO, the East Coast Homophile Organizations, in 1965.

Stein’s agenda was not to retell this story, but rather to use it as a window into historiography. The importance of Drum, he argues, was self-evident: not only did it successfully pave the way for more graphic and erotic gay representations and clearly anticipate aspects of gay liberation culture, but it also had far more expansive circulation than any of the more canonical homophile periodicals, such as ONE, Mattachine Review, or The Ladder. Since canon-formation is precisely the outcome of the three factors in Stein’s subtitle, the question becomes, why the omission of Drum in the more familiar narrative of homophile politics—and, as a corollary, how does restoring it force a reconsideration of respectability politics?

To that end, he turned to the foundational moments of modern U.S. gay historiography, namely the publications of Jonathan Ned Katz’s Gay American History (1976) and John D’Emilio’s Sexual Politics, Sexual Communities (1983). Katz’s pioneering book blended documents and analysis, uncovering a staggering wealth of queer material hidden among the country’s archives and historical periodicals, acting as a wakeup call and rallying cry for a generation of LGBT historians. D’Emilio’s landmark monograph revealed the then-largely-forgotten history of the homophile movement, left in the shadows of gay liberation after Stonewall. Neither paid any substantive attention to Drum, and Stein wanted to know why. Instead of speculating, he simply asked; Katz and D’Emilio remain active and central gay historians, and recounted their methods with him. Ideology played one important role. While Katz recalled some passing familiarity with Drum, he hadn’t seen it as politically significant; informed by the anti-capitalist sentiment of gay liberation, he viewed Polak’s consumerist bent as potentially reactionary, and certainly at odds with the liberationist ethos.

Research methods, too, helped exclude Drum from D’Emilio’s book. By the 1970s, as the then-grad-student undertook his doctoral work, he benefitted from interviews and documents supplied by several important homophile activists, from Harry Hay to Barbara Gittings. By that point, the troubled, often personally abrasive Polak had fallen out of favor with many of these figures (Polak would tragically commit suicide in 1980). So while a small set of Polak’s papers later became available at the ONE National Gay & Lesbian Archives in Los Angeles, during D’Emilio’s research he remained a less visible and accessible figure, further marginalizing him in the narration of the homophile movement. Drum itself remained elusive even as Stein began doctoral work in the 1990s; since no single archive held a complete run he ultimately had to track it down at scattered repositories.

Despite Stein’s enormous intervention in City of Sisterly and Brotherly Loves, the omission of Polak and Drum still remains largely the case. While LGBT archives have grown tremendously in the past two decades, Drum is still quite rare (though as was noted from the crowd by archivist Bob Skiba, the wonderful John J. Wilcox, Jr. LGBT Archives at the William Way LGBT Community Center near the Historical Society has at least a near complete set of Drum, and plentiful other queer archival treasures). And importantly, as digital research begins to edge out the physical archive for many researchers (a tendency Stein finds troubling, while acknowledging the obvious benefits of increased access to information), the vast gaps in the online archive reinscribe many of the same omissions.

Stein concluded with a fascinating examination of the business discourse at EBSCOhost, whose large but incomplete LGBT Life collection includes several homophile periodicals, but not Drum, whose sexual content seems to have triggered corporate red flags. With humor but also frustration, Stein recounted his interview with a high-ranking EBSCOhost figure, who attempted to talk around the loaded value judgments of this policy of queer elision by neither condemning Drum nor signifying any willingness to reconsider its exclusion. On a less ideological but equally irksome level, he also noted that their ostensibly full-text coverage of publications like ONE still omits letters to the editor, ads, and covers, leaving digital researchers with a compromised version of the magazines.

In other words, archives, history, and canons continue to collude in shaping queer memory. Stein is right to question this, of course, and this talk was a precursor to a longer article for the Radical History Review. It was tailored well for a diverse public audience (including some of Stein’s original interview subjects from the Philadelphia homophile movement, as well as relatives of those he interviewed for his recent book on Supreme Court sexual politics), and Stein was surely right to avoid getting bogged down in arcane-to-most historiographical questions. I will be interested to see, however, what he makes in the article of those whose work has run parallel to or been informed by his own, such as Martin Meeker’s questioning of homophile respectability through the para-homophile work of the Dorian Book Service and Pan-Graphic Press, or David Johnson’s recent rethinking of physique publishers and gay consumer politics. I wonder also what the copyright obstacles are to some enterprising archive (or blogger) simply putting scans of Drum up for all to read. In any case, this was an enjoyable, informative talk from one of our premier LGBT historians, in the right place and at the right time!

Whitney Strub is an associate professor of history and director of the Women’s & Gender Studies program at Rutgers University, Newark, where he works with the Queer Newark Oral History Project. He is the author of Perversion for Profit: The Politics of Pornography and the Rise of the New Right (Columbia, 2011) and Obscenity Rules: Roth v. United States and the Long Struggle over Sexual Expression, and he blogs about Newark, film, and queer history.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com

I enjoyed Marc’s talk as well, Whitney. His point that Clark’s place in the gay rights movement has been largely overlooked because of Drum’s lack of “respectability” is well taken. There’s been a subtle trend in the last 20 years to take the sex out of homosexuality.

Notches is very pleased to report that Marc Stein’s article “Canonizing Homophile Sexual Respectability

Archives, History, and Memory” is now available online (with subscription) in the Radical History Review, Fall 2014, Number 120: pp. 53-73. The abstract is available at: http://rhr.dukejournals.org/content/2014/120/53.abstract

Our congratulations to Marc on the publication of this important article.

Thank you so much for summarizing Stein’s talk. Fascinating insights into the sociopolitical context and methodological choices informing Katz and D’Emilio’s early work, and thus so much of the subsequent narratives. I’ll be keeping an eye out for his Radical History Review piece.

I knew Drum existed. Now I know I must know it better.

Pingback: tallying notches | strublog