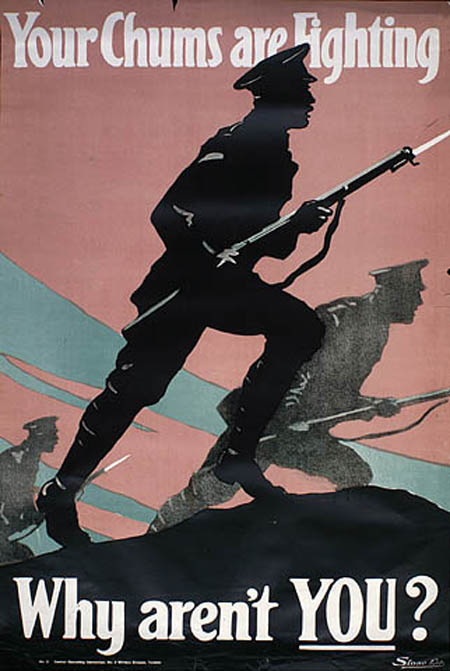

The world has just commemorated the 100th annivesary of the beginning of the First World War. While most historians have come to categorize the war as, in the words of Richard Evans, ‘the seminal catastrophe of the entire period’, ideologically driven government officials and some military historians insist that the war was a triumph of good over evil, and a resounding victory for Britain and its allies. Many controversies have therefore arisen about who, what, and how to commemorate, and about the very nature of the war itself.

In this post, I’ve chosen to commemorate some drunk Canadians in London in 1916, the police who impersonated them, and the women who sold sex in the bars that they frequented. With a title like this, of course I want to entertain. But I also want to argue that the sexual history of war lies at the very heart of the history of war itself.

Prostitution in London rose dramatically during the First World War, but so too did promiscuous relations more generally. Police officers struggled to apply laws against street prostitution — which required that they identify suspect woman as a ‘common prostitutes’ — to growing numbers of women who were cavorting with soldiers and other men on the street. Said to be suffering from ‘khaki fever’, young women were drawn to the excitement (and the uniformed men) that the war brought to the heart of London. London’s West End and Soho in 1916 were among the epicentres of the war: troops were housed in this area, and many others flocked to the pulsing and brightly lit streets to enjoy booze, sex, food, and entertainment. Couples canoodled down Soho’s countless small alleys, nightclubs appeared behind unassuming doors and up staircases, and cocaine could be increasingly found in the cafes, clubs, and public toilets.

By 1916, Charlotte Street, North Soho, had become infamous for such imbibing — of both alcohol and sex. Today it’s a street where historians leaving IHR seminars go to enjoy the myriad Korean, Italian, Indian, and Thai restaurants; in 1916, it was lined with Belgian, French, Russian and Romanian cafes. These cafes were run by refugees from the Continent who provided illegal alcohol late into the night to desperate men on leave from the trenches after the Defense of the Realm Act restricted the opening hours of licensed premises.

Several complaints of drunken soldiers zig-zagging down the streets around Tottenham Court Road in the wee hours of the morning put pressure on the Metropolitan Police to address the problem. So D Division, North Soho, deployed their very best plainclothes officers to see what was really for sale in these cafes. To their disappointment, they were offered only coffee and tea. It seemed that street clothes made them stick out every bit as much as a policeman’s uniform.

The Met needed a solution, and contacted the Commander of Canadian Troops in London, who responded to D Division’s request for two Canadian uniforms in the affirmative. He tersely insisted, however, that they be returned clean. The uniforms proved effective for use in this undercover operation: posing as well-paid and notoriously bacchanalian Canadian soldiers, the officers were offered gin, whiskey and beer — and also a ‘short time’ upstairs with some of the bar’s female patrons. With this evidence, police proceeded against the cafes under the Defense of the Realm Act, and they closed their doors (albeit temporarily).

It’s a funny story, and the immense market for commercial sex that was created in London between 1914 and 1918 was of course about excitement, entertainment, and reckless abandon. It was about soldiers out on the town to calm their nerves and preserve their sanity; about plucky policemen impersonating Canadian accents; and about young women enjoying the new sexual and social freedoms that the war had accelerated.

But this market for commercial sex during the war was also born of trauma, inequality, violence, and displacement. Military culture encouraged — or at least explicitly tolerated — the use of prostitutes and made men (and boys, which so many of them were) feel that it was a crucial part of their life as a soldier. These young men, who often had no sexual experience whatsoever, found themselves in a brutal and disillusioning world where the lights of nighttime Soho stood in disjointed contrast to the horrors of the front lines. As historians such as Jessica Meyer and Joanna Bourke have argued, men during the First World War struggled and suffered in many ways under the demands of a patriarchal and militaristic masculinity. Immense peer pressure and fear stoked the market in bought sex, alongside misogyny, the normalization of the idea of an uncontrollable male sex drive, and youthful curiosity. As UCL historian Clare Makepeace recently described in a public lecture, behind the water-logged trenches on the front lines in France, regulated brothels had queues out the door. Meanwhile, in Soho, women lined the streets and filled the clubs. Visible and regulated prostitution was a crucial part of the wartime landscape.

The women who sold sex, meanwhile, found themselves the victims of both frequent client violence as well as legal injustice. Often arrested without cause and subject to police harasssement, women were marked with a criminal record as a ‘common prostitute’, and were fined or imprisoned. Some soldiers, many of whom were surely suffering from what we now call PTSD, attacked prostitutes, their violence facilitated by the way in which the sex industry had been driven underground. Meanwhile, commanding officers demanded that women’s potentially diseased bodies be made ‘safe’ for the troops — a matter of military efficiency, considering at least one in ten soldiers were on leave suffering from syphilis. By 1918, the War Office had approved a measure which criminalized the spread of venereal disease by women (and women alone), whether she knew she had a sexually transmitted infection or not, and regardless of the possibility that the man had actually given it to her.

These are difficult things to reconcile with our commemoration of war as a noble fight against evil. Some would say that recognizing the sexual history of war trivializes the bigger picture of sacrifice and heroism. But I think it is very important to acknowledge that many of the young and green men who marched off to war were buying sex in the illegal cafes of Soho. We know from compelling historical evidence, and from the wars that followed and continue to rage around the world, that prostitution and sexual violence against women are an absolutely central part of warfare. Sometimes, this prostitution could be a way for women to survive, even earn some ready cash, in a socially unequal and disrupted world; and a way for terrified men to comfort themselves between stints in the trenches. At other times it could be another manifestation of the terrible violence and fundamental inequalities of war, a war waged on the home front as well as the front lines, and against more than one perceived enemy. The history of sexuality and war is not a simple one. Lest we forget the drunk Canadians in London in 1916, and the exciting, troubling, and complicated world they lived in.

Julia Laite is a lecturer in modern British history at Birkbeck, University of London. She is interested in the history of women, gender, sexuality, crime, migration, prostitution, and occasionally lorries. Her first book, Common Prostitutes and Ordinary Citizens: Commercial Sex in London, 1885-1960 was published with Palgrave Macmillan in 2011. She is currently working on trafficking and women’s migration in the early twentieth century world.

Julia Laite is a lecturer in modern British history at Birkbeck, University of London. She is interested in the history of women, gender, sexuality, crime, migration, prostitution, and occasionally lorries. Her first book, Common Prostitutes and Ordinary Citizens: Commercial Sex in London, 1885-1960 was published with Palgrave Macmillan in 2011. She is currently working on trafficking and women’s migration in the early twentieth century world.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com

I’m always chary of using PTSD in relation to the psychological traumas of historic figures, but thank you for drawing the link between psychological trauma and violence. It is an all-too-often overlooked facet of the condition, at least as it is constructed historically.

Yes, thanks so much for pointing that out. I was chary of using it too, but then went with it in the name of something recognizable to a modern non-historian audience that didn’t take too long to explain. But it’s a very important point. Do you know of any work that was done at the time about men’s (sexual and domestic) violence and their psychological trauma from war? Seems unlikely, considering, as you say, it’s overlooked even today.

There are accounts in two novels I’ve read (dating from 1920s and 1930s) about men who were violent domestically after returning from the war, and a direct correlation was made between their experiences and their behaviour. If this suggests it was a known phenomenon, then there could be something, somewhere recording ‘real life’ examples? Court records? Medical history? Admission to psychiatric institutions? Unfortunately the two books I’m thinking of are on my mother’s shelves in New Zealand, so I can’t give a reference. Definitely in Virago Classics series though.

The issues you raised here were shared by New Zealand soldiers at the same time. Official response here was framed by the growing ‘tightening’ of social morals. When a woman, Ettie Rout, began issuing prophylactics to Kiwi soldiers heading off on leave from the front there was an official scream up to Prime Ministerial level. I read the archival file for my book on the Kiwi experience (‘Shattered Glory’ Penguin 2010). Extraordinary. The NZ divisional command were pragmatic enough to tacitly accept the need but arranged for condom distribution via the chaplain, with a moral lesson attached. A political solution, of course.

Thanks for providing this perspective on the social tensions in place during WW1. I’ve shared it on Facebook… 🙂

What a great post. Sure, we’re quite enthousiastic about most posts on alcohol but this was very interesting. Cheers,

Micky

Fascinating research into a period I’m currently writing about myself. Thank you.

Reblogged this on MeaningfulMeanings and commented:

The world has just commemorated the 100th annivesary of the beginning of the First World War. While most historians have come to categorize the war as, in the words of Richard Evans, ‘the seminal catastrophe of the entire period’, ideologically driven government officials and some military historians insist that the war was a triumph of good over evil, and a resounding victory for Britain and its allies. Many controversies have therefore arisen about who, what, and how to commemorate, and about the very nature of the war itself.

Reblogged this on bemsigal.

Reblogged this on Life in Ottawa and commented:

Interesting story and one that points out the realities of war and combat. Learning of the use of Canadian uniforms by the London police to learn what was actually being sold on the streets provided a history lesson I was previously unaware of. We often don’t hear of the mental stresses these soldiers went through in those days, but it seems given the circumstances of the limited technologies and the way battles were conducted, this had to have weighed heavily on those involved. Excellent post and one Canadians should read to learn of the history of our military in all aspects, even those that are somewhat sordid.

A great job of connecting the dots of social dislocations.

Interesting read!

Reblogged this on The Past in the Present and commented:

Interest look at an often forgotten aspect of war.

Reblogged this on Free Caveat and commented:

very interesting piece written by Julia Laite, a lecturer in modern British history at Birkbeck, University of London.

Refreshing to read about the WWI with a nuanced perspective

well done.