Interview by Justin Bengry

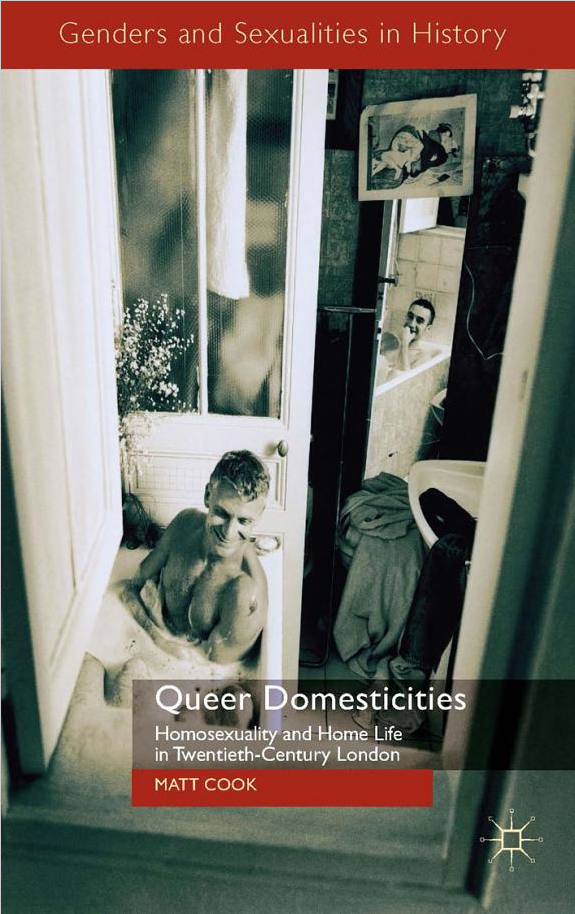

In Queer Domesticities: Homosexuality and Home Life in Twentieth-Century London (Palgrave, 2014), Matt Cook explores queer men’s experiences of home and homemaking in the metropolis. Peering into bedsits in Notting Hill and squats in Brixton, as well as luxurious abodes in the city’s more affluent districts, Cook offers a queer history nuanced by class and race. Cook’s study sensitively depicts the ways queer men experienced their identities, home, family life and communities across the twentieth century. An important and significant break with previous studies, including his own, that privileged public arenas in the formation of homosexual subcultures, Queer Domesticities instead illuminates how the personal and the private contributed to building interconnected relationships and communities. In a series of case studies, Cook focuses on various experiences of home life. The book draws from a remarkable archive of decades of oral testimony, to build a picture of urban queer life that simultaneously contextualizes and also undermines the stereotypes of queer men as arbiters of taste and style or gentrifiers of neighbourhoods.

Justin Bengry: We often think of home as a private refuge, but for many of your subjects home was never a private space. Often including extended families and boarders or domestic servants, home could be a very public place. What impact has the non-private nature of home, mediated differently by class positions, had on queer domesticities?

Matt Cook: It struck me really profoundly during my research for this project just how much our expectations about access to private space have changed over the last half century. Between overcrowding for the poor and live-in servants for the rich, home usually offered little privacy. It really might not feel like the safest place to be doing anything illegal – and that of course included sex between men. With people constantly coming and going, even the most chaste of queers might also have felt the need for caution on the home front lest tell-tale domestic signs compromised their respectability or masculinity. Men who owned or rented their own mansion flats in Mayfair or cramped bedsits around Paddington were still under regular surveillance – from nosy landladies or landlords, a concierge, neighbours separated by the thinnest of partitions, or else cleaners or other domestic workers. These circumstances meant queer domestic lives were necessarily often lived with a large degree of self-consciousness and caution. This was especially the case for poorer men living in very close proximity to others (and most often without a room of their own) and without the safety net of privilege.

And yet if this all brought very real difficulties for these men and led many of them into various degrees of trouble, queer lives were nevertheless forged in these contexts and within these networks of friends, co-residents, neighbours, family, and domestic servants – and not only in spite of them. These circumstances shaped part of what it meant to be queer. I found it rather moving the extent to which these various others were often folded into networks of intimacy that made everyday life tolerable and companionable – however irritating and intrusive they could also be. I ended up describing home lives that were much more heterosocial and heterogeneous than I first imagined I would.

The openness and semi-public nature of home meanwhile offered up some possibilities for self-definition. For many middle- and upper-class queer men in particular, home became a place to demonstrate their taste and culture to others and to themselves. It was a way of denuding assumptions about queer degradation.

JB: Would it be fair to characterise a major point of your scholarship as stating that the queerness of home is not necessarily a product of the sexuality of its inhabitants? If so, how do your case studies illuminate queer homes even in the absence of homosexual partnerships?

MC: Yes, absolutely. There was no particularly stable concept of what it meant to be queer and what it meant for men to have an emotional and sexual relationship together. It follows therefore that there was no stable or necessary link between being queer and establishing a certain sort of home. Class position was much more unifying. There might not be the time, space, finances or desire to put any supposedly queer touch or twist on rooms you inhabited – and maybe inhabited with your wife, children or other co-residents who were keen to style or decorate to different tastes. Conversely, ostensibly ‘normal’ men, whose sexual desires were largely directed towards women, might still live in somewhat queer configurations (in partnership with close male friends, for example) and/or might decorate their homes in aesthetic, Bohemian or so-called ‘amusing’ styles which were being associated with avant garde, feminised and queer taste. Queering interiors – knowingly or not – might be a way of tugging at prevailing norms without necessarily making a statement about sexuality. Moreover, the rise of the queer interior designer (something I look at in some detail) meant that many homes were subject to the supposedly intrinsic stylish flourish possessed by these new professionals even though there were no queer men in residence. There was a real leakiness in the identifications and styles I investigated for the book, and there was an uneven investment in them amongst men who indentified in some way as ‘queer’ and amongst others who saw themselves as ‘normal’. It is the circulation, cross-overs and traffic of meanings that so fascinated me – not least because it muddies neat categorizations and assumptions about the ways people live (whatever the direction of their desires). It is part of the tension between trenchant stereotypes and assumptions on the one hand and everyday life on the other.

JB: Queer theorists have posited that investment in home, and related complicity with capitalism, contributes to a depoliticized homonormativity. How does your study support or refute these associations of queer domesticity with homonormativity?

MC: I think that it is too simplistic to figure home as apolitical or hetero- or homo-normative. Romantic socialists Edward Carpenter and Charles Ashbee through to the squatters and communards of the Gay Liberation Front have shown how home and the organization of domestic life could be a part – and a fundamental part — of living radically and exploring what radicalism associated with sex, gender and sexuality might mean. More prosaically home has often been a place where queer men have found room to express themselves in ways that were curtailed elsewhere. Even on that level there is radical potential in home-making. That said, my argument in the book is that places and people are rarely simplistically normative and conservative, or queer and radical. Each of my case studies can be shown to speak to each of these ‘positions’ or pulses in life, politics and culture. Men identifying as queer in one way or another have used their homes to counter prevailing cultural norms and to forge space for themselves. Yet, they have also in other ways adhered to those norms, finding through them a way of anchoring themselves socially and culturally.

JB: The Sexual Offences Act (1967) codified the ‘respectable’, domestically stable, monogamous couple as the only valid option for gay men. After the Act, Rex Batten and his partner, as you describe in Chapter 5, finally felt safe buying a double bed. But did even the ‘respectable’ queer couple encounter new tensions and challenges following their decriminalisation?

MC: There were challenges and pressures that came with visibility. Some of my interviewees described an escalation of abuse and also a felt pressure to be more radical, more visible, to come out and define themselves in particular ways. Some just wanted to continue to fit in as best they could. In addition – as the AIDS crisis vividly and tragically illustrated – partial de-criminalisation in 1967 did not help the men who lost their homes when their partners died, or those who were unable to get mortgages because of their sexuality or HIV status. Particular pressures and anxieties were a part of everyday life for many gay men post 1967.

JB: What groups or individuals were you unable to include in the study that would have illuminated other facets of queer domesticity? Was this on account of source material concerns or other factors?

MC: The project was potentially infinite: everyone has a home life of sorts, even if only aspirationally. Everyone I spoke to about the project seemed to have another case study to offer up or another idiosyncratic home for me to pursue. It was hard making choices and I made them in the end on the basis of the sources I could draw on and also in relation to the thematic areas that were beginning to fall into place. But I am very aware of the gaps and silences in my account. I start the first section of the book with a discussion of homelessness but it is testament in part to the difficulty of tracking the home lives of poorer and homeless men. The issue of homelessness has been so pressing for many queer men, yet too often we are unable to tell specific stories and are instead only able to refer to the homeless as a group and so misleadingly imply a homogeneity of experience. I was very aware too of how disproportionately white my account is, reflecting in part the ways in which queer and gay lives have been rendered culturally. I do try to engage critically with the relationship between race and gayness — partly via my Brixton and Notting Hill case studies and the home life of photographer and artist Ajamu X. He had some very interesting things to say about intersections of Afro-Carribean and queer ‘family’ cultures in particular. It would have been great to pursue that further.

JB: Much of queer history has emphasized the significance of the public ‘scene’ and urban sites of commercial sociability as important factors contributing to individual and collective queer identities. How does your own scholarship complicate other historians’ emphasis on public lives?

MC: Those public lives and histories are incredibly important. Most of us (and I mean gay or straight, queer and ‘normal’) are in some sort of dialogue with them – as places to visit, spurn, deride or celebrate. But my argument is that such dialogues are fundamentally modulated by our experiences of domestic spaces and family life. This really helps to complicate the apparently simple division of public and private. Just as interactions with the putatively public spaces and realms are shaped by domestically inflected assumptions and identifications, so those home and family lives are fundamentally shaped by wider (public!) political, social and cultural pressures. It’s a messy and symbiotic relationship – and one that I’ve tried to get to grips with in the book.

JB: You are in the unique position of having undertaken oral history interviews with south London activists and squatters who were interviewed twice before by others undertaking histories of the squats in 1983/84 and again in 1996/97. You can therefore trace changing lives and responses to the past across several decades. How did this opportunity to explore long-term responses affect your study?

MC: This was an amazing experience. Firstly, the men I interviewed were very skilled analysts of their own pasts and the social, cultural and domestic dynamics they encountered. I learned an immense amount from them. Their analyses also shifted across the three interviews – modulated by the contexts in which each interview was recorded (first as the squats were being disbanded; second after several squatters had died of AIDS related illnesses; and finally after successive pieces of equalities legislation but also – to some – the loss of an energizing radical pulse). The successive interviews told me a lot about the squats in the 1970s. They also revealed a lot about these successive moments and the time that elapsed between them. Mourning, loss and nostalgia inflected the way interviewees remembered the 1970s from the vantage point of 1996, for example. In addition they revealed an investment in history as a way of orientating gay and queer lives now.

JB: Chapter 7 discusses the gay men of the Brixton squats, many of whom could squat precisely because of their social and cultural capital. To what extent were these squatters aware of or engaged with the lives of men and women squatting out of necessity and poverty? How was this privilege inflected by race?

MC: This is a difficult question because most of the squatters were very politically engaged, very aware of their privilege or disempowerment associated with class, race and gender. Many of them came from working-class backgrounds and had been the first in their families to go to university as part of the expansion of Higher Education in the post-war years. Several were poor themselves; squatting was for them a pragmatic solution or a necessity as well as a politicized choice They picketed Brixton police station in protest at the arrests of local black men and women. And yet – as several observed in retrospect – they could in some ways be insensitive towards or simplistic in their thinking about the inclusions and exclusions the squats enacted. A stated inclusivity did not mean that the squats felt accessible to the working-class men who squatted nearby or the black queer men who squatters socialized with a little at a local shebeen [illegal bar]. Many of the squatters, as you suggest, had social and cultural capital which made them mobile and opened up possibilities then or in their futures which were much more remote for others living in the area.

JB: Queer Domesticities takes as one focus the changing demographic patterns of London’s neighbourhoods. To what extent does the stereotype of the affluent queer gentrifier obscure the reality of many gay men and lesbians who remain economically marginalized and threatened by the loss of homes (or already homeless) as London became increasingly expensive?

MC: This is an important strand of my argument. This stereotype does obscure most queer lives. That said, it is also true that some queer men have had greater disposable income than women and couples (gay or straight) with children. If some of these men were drawn to swanky new build apartments, others bought larger properties in cheaper areas undeterred by (supposedly) poorer schools and able to devote time, money and energy to doing their properties up. They have had a visible impact and have been taken up disproportionately in the press and elsewhere.

JB: How does understanding queer domesticity and home life influence your next research project?

MC: I’m juggling two prospective projects – one on AIDS and the 1980s, the other on non-metropolitan queer lives in England. My thinking about both of these projects has been shaped by this work on home, family and domesticity and the significance of those places and intimate networks to everyday life and experience. An historical analysis of government policy on AIDS, for example, only gets us so far in understanding how individuals and their networks of friends and family dealt with the day-to-day realities of the crisis. I’ve become much more engaged with the latter as a result of this work on the home.

Matt Cook is a Senior Lecturer in History and Gender Studies at Birkbeck, University of London. Matt is a cultural historian specializing in the history of sexuality and the history of London in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. He is Birkbeck Director of the Raphael Samuel History Centre and an editor of History Workshop Journal. Matt is also author of London and the Culture of Homosexuality, 1885–1914 (Cambridge, 2003), editor of A Gay History of Britain: Love and Sex between Men since the Middle Ages (Greenwood, 2007), and editor with Heike Bauer of Queer 1950s: Rethinking Sexuality in the Postwar Years (Palgrave, 2012) and with Jennifer Evans of Queer Cities, Queer Cultures: Europe since 1945 (Bloomsbury, 2014).

Matt Cook is a Senior Lecturer in History and Gender Studies at Birkbeck, University of London. Matt is a cultural historian specializing in the history of sexuality and the history of London in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. He is Birkbeck Director of the Raphael Samuel History Centre and an editor of History Workshop Journal. Matt is also author of London and the Culture of Homosexuality, 1885–1914 (Cambridge, 2003), editor of A Gay History of Britain: Love and Sex between Men since the Middle Ages (Greenwood, 2007), and editor with Heike Bauer of Queer 1950s: Rethinking Sexuality in the Postwar Years (Palgrave, 2012) and with Jennifer Evans of Queer Cities, Queer Cultures: Europe since 1945 (Bloomsbury, 2014).

Justin Bengry is an Honorary Research Fellow at Birkbeck, University of London. Justin’s research focuses on the intersection of homosexuality and consumer capitalism in twentieth-century Britain, and he is currently revising a book manuscript titled The Pink Pound: Capitalism and Homosexuality in Twentieth-Century Britain. He tweets from @justinbengry

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com