Interview by Robert Self

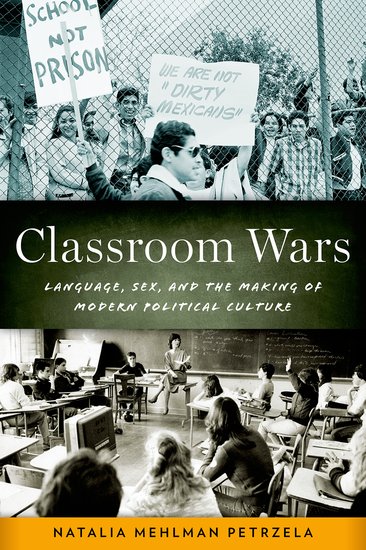

The schoolhouse has long been a crucible in the construction and contestation of “family values.” In Classroom Wars: Language, Sex and the Making of Modern Political Culture (Oxford, 2015), Natalia Mehlman Petrzela focuses on battles over sex education and bilingual education in order to chart how Californians navigated the sexual revolution, school desegregation, and a dramatic increase in Latino immigration since the 1960s. Taking readers from the cultures of Orange County mega-churches to Berkeley coffeehouses, Petrzela’s history of these classroom controversies highlights the rightward turn and enduring progressivism in postwar American political culture.

Robert Self: My own experience in the archives convinced me that more than any other single issue—with the exception of abortion—what animated activists on the religious right in the late 1960s and 1970s was the secularism of public schools. How did sex education serve as a catalyst for those concerns?

Natalia Mehlman Petrzela: One popular quote that encapsulates the spirit of many of the protests against sex education in this era was a frustrated father who said, “They took God out of the schools and they put sex in!” He was referring to the Engel v. Vitale Supreme Court decision (1962) that disallowed prayer in public schools; to some parents this timeline from Vitale to the efflorescence of sex education programs in the second half of the decade—not to mention a simultaneous series of cases that narrowed the definition of obscenity—signaled troubling social upheaval.

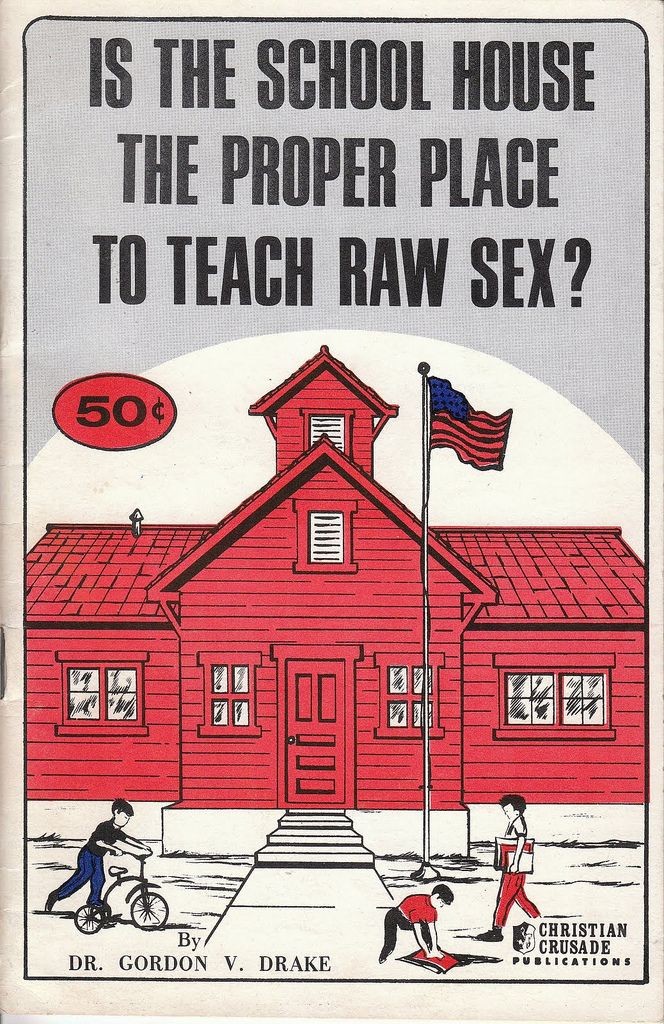

The rhetoric of sex education opponents, or the “Antis”, suggests that much larger issues were at stake: a filmstrip about masturbation elicited accusations of communist conspiracy, mention of homosexuality spawned uproars about the perversion of the educational establishment, and the Antis tarred a lesson on cultivating critical thinking as antipatriotic. Sex education programs enjoyed renewed energy in the 1960s, and the intentions of most programs were quite moderate in seeking, as opponents did, to stem the effects of the sexual revolution on young people. Not that most opponents bothered to read the curricula at stake! It became very clear that by the late 1960s there was a broad panic among conservatives and even previously apolitical moderates about the infiltration of a “new morality” in school and in society – sex education came to stand in for these transformations, especially as it appeared to be an affront to traditional authorities including parents and churches.

RS: In Classroom Wars, you treat controversies over sex and language since the 1960s. For many readers, this might not seem like an intuitive combination. As your research progressed, how did you come to see the two issues as linked?

NMP: In April 1969, when Governor Ronald Reagan took the stage at a state conference for bilingual education, he addressed a public increasingly radicalized by the Chicano movement. Activists tossed lit firecrackers around the governor and started several small fires in wastebaskets near the stage. Reagan continued to speak until the activists clapped and chanted in Spanish so loudly they drowned him out. Similar passion infused controversies over California’s implementation of nationally acclaimed sex education programs. In 1968, Reagan declared that these curricula signified the “moral crisis into which [California was] descending” and convened, along with his fellow conservative, Superintendent of Public Instruction Max Rafferty, the Moral Guidelines Committee. Reagan and Rafferty stacked the committee with their appointee picks and entrusted it with what Reagan called the “single-most important task before California”: crafting moral guidelines for its increasingly diverse school system.

As governor of a state undergoing profound political and cultural transformation, Ronald Reagan perceived sex education and Spanish-language bilingual-bicultural education as symbolic of larger changes even as he was caught up in these very struggles. Yet historians have underexplored these curricula even as they converge in several (surprising!) ways.

Educations and politicians introduced both curricula in newly energized forms in the 1960s, largely due to the influx of Mexican Americans and the sexual revolution, which gave educators new urgency. Despite promoting quite moderate social and political ends, they were both quickly portrayed as evidence of the era’s social dislocations by a growing conservative movement that targeted them as evidence of the unraveling social fabric. The arguments over both these curricula also centered on “the family” in fascinating ways; in the case of sex education, mostly white families argued that parental values should be privileged over those of the “hippie sex educators.” In some ways very similarly, advocates of bilingual-bicultural education insisted that their families’ background and culture deserved recognition in the schoolhouse. These struggles were both born of the civil rights era’s new focus on identity and individualism but played out very differently, and I argue this had everything to do with race and region.

RS: It seems to me that public schools are underrepresented in post-World War II U.S. historiography. Scholars of the Progressive era see the rise of public schools, especially high schools, as crucial to state-building and to lengthening notions of childhood. In what ways might we see public schools in later decades as equally central to histories of the state, politics, and childhood?

NMP: For all three of the reasons you mention, schools are just as crucial to the postwar era as to the early 20th century. However, in this period, we see an expansion of the role of the state, a transformation of the meaning of politics, and an active redefinition of the meaning of childhood by young people and by adults. This period witnessed an unprecedented federal involvement in schools, which meant that in a country defined by its educational localism, there existed for the first time since perhaps even the founding, national conversations about the purpose of American schools writ large and its relation to the state at the municipal, statewide, and federal levels. One impetus for federal involvement was the Brown v. Board of Education (1954) decision, which led to new forms of oversight and politicized education explicitly in new ways. Opposition to Brown was not only about racist sentiment, but also about a deep discomfort regarding the federal government deciding such previously local, intimate decisions such as where children would go to school. This unease was intensified when this involvement only grew with the elaboration of LBJ’s Great Society.

The schools – K-12 and college – reflected, and more importantly, were crucibles for broader social upheavals and cultural shifts: examples of these are demonstrations against dress codes and parietal rules as well as for freedom of speech and greater “relevance” of course matter. It’s on these campuses that young people militated against restrictions on their political beliefs, ethnic identities, and intimate lives. These protests both drew energy from the activism in the political climate at large and set the foundation for organization beyond the schoolhouse. For example, in the walkouts of 1968, students found inspiration in part from the passage of the federal Bilingual Education Act, but also became crucial in in the movement for future, larger reforms such as the reauthorization of state bilingual funds or even the Lau v. Nichols Supreme Court decision of 1974, that helped solidify the state’s commitment to linguistic minorities. It is also important to remember that when the youth walking out of high schools demanded minority teachers and administrators, recognition of their culture, and a voice in school governance, they claimed rights in new ways specifically as young people. They were both acting as political agents at a younger age and perceiving “youth” as a more extended identity, temporally and in terms of the privileges they could enjoy even as teenage students with unprecedented energy and ability to shape their educational experience.

Many parents and adult citizens placed the school at the center of their political vision as well, and fought bitterly about programs that were relatively minor parts of the curriculum, such as sex education. Opponents to sex education actually argued, and gained national support for, proposals to eradicate the programs as a communist plot to pervert American children.

RS: Childhood as a concept and children as people became central to the left-right culture wars beginning in the 1960s, with antecedents in earlier decades. Why did both the broad left (from racial nationalists to feminists and gay rights activists) and the far right come to focus on children during and after the 1960s?

NMP: Many adults turned their attention to young people because broad social upheavals made them anxious about the future of the nation. In the case of those on the left, the thrust of this attention was to extend more privileges and autonomy to young people; we see this both in a case like in re Gault (1967) which granted greater rights to juvenile delinquents and in curricula such as the “values-clarification” pedagogies that emphasized children developing their own decision-making faculties independent of their parents’ or teachers’ perspectives. The activism of high school and college students (more so on the left, but on the right too in organizations such as Young Americans for Freedom) is best understood through this lens of youth empowerment.

By contrast, conservatives also homed in on children, but mostly to highlight their vulnerability and how the era’s social revolutions jeopardized their innocence – how much young people needed increased protection by their parents. These perspectives could collide in fascinating ways: In 1969, at a packed, contentious hearing about sex education, conservative opponents of the program were shouting down advocates and claiming that sex education endangered innocent children. Then, an adolescent student spoke up and said he actually valued the programs greatly and expressed the kind of independent viewpoint that such “innocent children” were not supposed to harbor. The opponent ended up screaming at the student, yelling, “I bet you’re not even a virgin anyway!” As soon as young people began expressing their perspectives on this issue, it became very clear that this generation was thinking independently, that this independence had everything to do with rejecting the traditionalism of their parents, and that new attitudes toward sexuality were crucial to forming their worldview.

RS: Your account of the politics of bilingual education in California reveals a deeply textured debate about language in Mexican-American communities. That debate has largely been erased in the traditional left-right culture wars framework. What does your recovery of that textured debate tell us?

NMP: Academics have been slow to integrate a rich history of Latinos in the US with the similarly rich culture-wars literature. This scholarly absence is noteworthy given that one of the biggest demographic shifts in the late 20th century has been the influx of Spanish-speakers, which inspired an attendant fear among cultural conservatives of a “Latinization” of the US. During the formative years of the culture wars – let’s say the 1960s and 70s –citizens and policymakers understood the “Latino issue” as peculiar to the southwest. For example, Max Rafferty, a prolific conservative media personality and California politician with a national following talked about the “race question” all the time in syndicated media outlets, but always referred to black-white relations except when he targeted his California constituency, who grappled with the presence of Spanish-speakers at the center of its racial politics. By today, as the rhetoric of any national candidate reveals, the fulcrum of discussions about race in America is often the Latino presence.

Bilingual education activism illuminates how this discursive shift and the political situation to which it refers transpired, and specifically shows how the rise of conservative politics and Latino cultural power were intertwined. During the 60s and 70s, the archives make it clear that conservative groups such as the Young Americans for Freedom fought repeatedly with radical Chicano groups, suggesting a proximity between these two movements that historians have overlooked. Also, and this was shocking, I learned that before bilingual education became politicized as a progressive issue, quite a few Republicans – including Max Rafferty – were at the forefront of implementing bilingual-bicultural education programs, some of which we would consider innovative today: in the mid-1960s Rafferty actually visited with the Mexican Minister of Education to initiate a textbook exchange and even publicly declared that “Anglo children have as much as responsibility to learn Spanish” as Latinos to learn English. This is very surprising given how reflexively bilingual education has been associated with the left since 1968.

Incorporating these histories into the traditional culture wars framework reveals that fights over foreignness and language were as important as controversies over race, and that different minority groups had very different, or even conflicting, agendas. For example, Latinos at times advocated against desegregation (a cherished cause to many African-Americans) because they needed critical mass to implement bilingual education programs. And, before Brown, they sidestepped the whole segregation issue maintaining that they were white and should attend white schools. Our notions of “identity politics” become significantly more complicated when we expand our sense of who the players in these conversations are.

Similarly, as I unearthed stories of how Latinos advocated for and grappled with the reality of implementing bilingual education programs in schools, I learned of all sorts of internal contestation among these communities, who could not be further from a monolithic group. For one, the “watershed” 1968 Bilingual Education Act actually privileged programs so moderate that a bilingual education activist with profoundly ambitious pedagogical aims, Ernesto Galarza, was actually limited by this act and even had to shut down his programs. This happened in an acrimonious fight with another group of Latino educators and bureaucrats who managed to win the federal allocations for their assimilationist program – a program Galarza described as lacking an authentic connection to Mexican culture and invoking “biculturalism” only for “dramatic punch.”

Debates over language education inspired conservative reactions among some Latinos, who called themselves “Americans of Mexican descent” and saw Chicano demands for Mexican-American educators as damaging, and even condescending, in suggesting Mexican-American students were incapable of learning from “blond, blue-eyed teachers.” These are nuanced and largely untold stories about the groups that will most transform American demographics, and possibly political alignments, in the 21st century.

RS: This book nicely shows how conservative political activists galvanized around opposition to what they called the “new morality” of the 1960s. Our contemporary political discourse encourages us to see “moral” conservatism and “economic” conservatism as distinct. Did you find this to be the case in California?

NMP: Here’s where bringing together multiple educational issues really sheds light on how interconnected moral and economic concerns were, and how central education was to their intertwining and grander political import. A powerful and vivid example is Proposition 13, the infamous 1978 tax revolt that slashed property taxes in California. The conventional wisdom is that public education was a casualty of Prop 13 (which it was), but I argue that concerns over education were central to the mounting support for Prop 13. By bringing together various educational questions, I show that frustration with the public schools, especially how they dealt in the 1970s with the new “moral concerns” over declining ethics and weakening patriotism, inspired a resistance to finance the public schools, an important and unacknowledged fount for Proposition 13. This is important not only to explain this particular anti-tax measure (which inspired many other tax revolts nationwide) but also to show that cultural concerns are just as “real” as economic ones, a fact we often overlook when these realms are considered mutually exclusive.

RS: Finally, Classroom Wars starts and concludes with the argument that sex and nationalism came together powerfully in right-wing discourses after the 1960s. I wanted you to have an opportunity to explain to readers (briefly of course so they’ll read the book!) how that combination worked, and continues to work.

NMP: Let me give an example to illustrate how conservatives and liberals yoked together sex and nationalism. Both were involved in promoting what I call a “patriotic morality,” and we see this take place in the wake of the fights over sex education in 1969. Here, Governor Ronald Reagan declared that the state had descended into “moral decay,” and convened a Moral Guidelines Committee (MGC) to counter that trend. The MGC’s charge was to reverse this collective dissipation by devising “moral guidelines” for the public schools – a task they had to undertake without invoking God, given the Supreme Court’s recent decisions. Observers nationwide followed the committee’s proceedings closely, and the meetings dragged on over five years. Reagan was shocked, as he thought his appointees would quickly come up with guidelines that echoed the views of his conservative constituents. Well, they did come up with an 80-page reactionary screed that condemned secular humanism, sensitivity training, communism, and John Dewey… but the Board of Education rejected it. Ultimately, it was the liberal faction on the committee – led by Reagan’s turncoat pastor– that prevailed.

This in itself might be surprising, given historians’ presumption that this era was defined by the rise of the Right. What I found even more counterintuitive was that the liberal faction’s guidelines were as attached to the importance of teaching a kind of national ethics based on family authority to American children as were the conservatives. This committee was born out of the bitter fights over sex education, but immediately took up not only a wide range of curricular issues but also the most profound questions about morality, patriotism, and family. Early in the group’s proceedings, one committee member quickly departed from the particulars of the sex education battles and said, “The real question we [the committee] must answer is ‘Which way America?’” Six years later, they could all agree that the social transformations of the 1960s had clouded the sense that Americans shared in a robust national purpose. Strengthening family authority vis-à-vis the school, a surprising cross-section of the polity could agree, was a surefire way to counteract this troubling trend, even as they disagreed on how to do it.

Natalia Mehlman Petrzela is Assistant Professor of History at The New School in New York City. She is the author of Classroom Wars: Language, Sex, and the Making of Modern Political Culture (Oxford University Press, 2015) and her writing has appeared in various scholarly journals and popular media such as The New York Times and Slate. Her new research focuses on the emergence of wellness culture in the postwar United States. She tweets from @nataliapetrzela.

Natalia Mehlman Petrzela is Assistant Professor of History at The New School in New York City. She is the author of Classroom Wars: Language, Sex, and the Making of Modern Political Culture (Oxford University Press, 2015) and her writing has appeared in various scholarly journals and popular media such as The New York Times and Slate. Her new research focuses on the emergence of wellness culture in the postwar United States. She tweets from @nataliapetrzela.

Robert Self is Royce Family Professor of Teaching Excellence and Professor of History at Brown University. His most recent book is All in the Family: The Realignment of American Democracy since the 1960s. He is currently at work on a book about houses, cars, and children in the twentieth century.

Robert Self is Royce Family Professor of Teaching Excellence and Professor of History at Brown University. His most recent book is All in the Family: The Realignment of American Democracy since the 1960s. He is currently at work on a book about houses, cars, and children in the twentieth century.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com