When the Supreme Court decided Griswold in 1965, birth control advocates might well have concluded that the decision marked a final recognition of the basic human need for reproduction control. It had taken fifty years to defeat the repressive, prudish and sexist ban on birth control that began in the 19th century. Furthermore, in the eight years between Griswold and Roe v Wade, eighteen states in the US repealed or loosened their prohibition on abortion. It seemed that acceptance of reproductive rights was on an unstoppable path to victory, much as gay marriage appears today. But this optimistic prediction proved wrong, of course, and another fifty years of a powerful campaign against reproductive freedom followed.

I don’t want to rehash what so many, including myself, have written about the anti-abortion movement. Instead I want to look at the fifty years before Griswold, in order to put that decision into context—and to understand why I consider it to have been too little, too late.

It’s been 101 years since the moment that I consider the opening of the modern movement for reproductive justice: in 1914, Margaret Sanger published the first issue of The Woman Rebel, a small feminist, socialist, and sex-radical newspaper. It published only seven issues until it was shut down by the U.S. Post Office. The reason? Since an 1873 federal law, any material relating to birth control—not just advocacy, not just advice about what it was and how to get it, but even philosophical discussion about whether it was a good idea—had been banned from interstate commerce. In her short-lived paper, Sanger was rejecting Victorian norms of shame and silence about sexual matters. She was also a socialist and a nurse concerned with working-class women, and she saw firsthand the ill health, poverty, and marital conflict that resulted from too many unwanted pregnancies. She tried to write about venereal disease for her regular column in the Socialist Party newspaper; when the Post Office ordered that article removed, the paper appeared with a big blank box under her regular headline, “What Every Girl Should Know,” a nice piece of visual sarcasm.

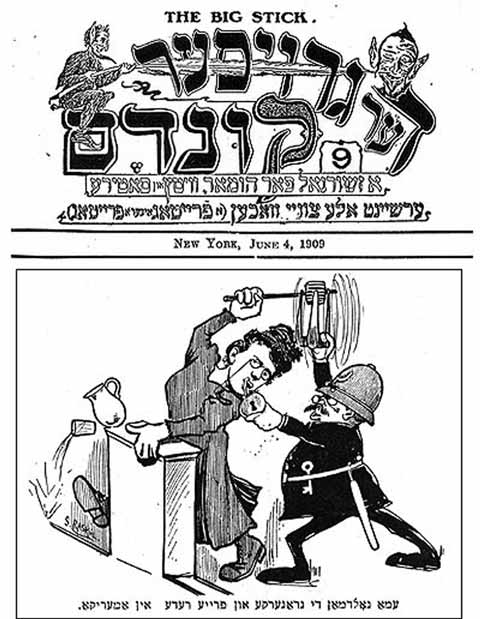

Margaret Sanger was by no means the first birth-control advocate in the US; she was following in the footsteps of Emma Goldman who had defied the law by distributing birth-control advice on the streets. But Sanger was a single-minded organizer and entrepreneur who kick-started a movement that would soon go national. After World War I, a movement for birth control spread to nearly every city and many towns in the US. Birth-control leagues began opening clinics in defiance of local laws. These were the heroic years of the movement, and many activists were arrested and jailed: Emma Goldman, Carlo Tresca, Jessie Ashley, Ida Rauh Eastman, Bolton Hall, Agnes Smedley, Mollie Steiner, Rose Pastor Stokes, Sanger herself and her sister Ethel Byrne in New York alone.

The movement evoked stiff resistance and vicious attacks, so advocates had to dig in for a long haul. The federal nature of the US required that this struggle proceed state by state. During that long struggle, the social movement of the 1910-20 period narrowed gradually into a set of staff organizations—that is, lobbying groups and clinics run by mostly well-to-do volunteers and a few paid staff members. These local organizations combined into the American Birth Control League, which then became Planned Parenthood in the 1940s. Needing to stay on the right side of law and Victorian morality, they confined their clinic services to married women. Constantly threatened by Christian moralists’ charges that they were destroying the family, they made several compromises and ideological shifts, and several of these haunt us today.

Compromise #1: The 1873 federal law and most state laws of that time banned all forms of reproduction control, both contraception and abortion. Most 19th-century discussions of the issue, pro or con, did not distinguish between contraception and abortion. But as the push for birth control began in the 20th-century, its leaders settled into a compromise: they would fight for the legalization of contraception while accepting the continued prohibition on abortion. The expanding availability of contraceptives reduced the incidence of illegal abortion, but it remained nevertheless very common, especially among poor and rural women. We will never know how our history would have been different had the early-20th-century birth controllers fought for legalizing all forms of reproduction control—might we have been spared the most recent half century of exhausting and resource-draining controversy over abortion? That continued fight against abortion has now circled back to an attack on contraception as well, a position that the Griswold decision seemed to have resolved.

Compromise #2: The early-20th-century birth controllers accepted laws that gave physicians the right to decide who was entitled to contraception (and, of course, to discreet abortions performed for well-off paying patients). To understand the significance of this compromise, note that up until 1960 and the marketing of hormonal birth-control pills, there was no form of contraception that required medical training. The best contraceptives for women before 1960, vaginal diaphragms, could not injure anyone; and someone could be trained to fit diaphragms accurately with a few days of instruction and practice. (Condoms, of course, were freely and cheaply available at every drug store—and they required no training either!) Thanks to these state laws that permitted physicians and only physicians to hand out contraception, doctors became moral authorities as well as health-care providers. Physicians, not married couples, decided who should have the right to contracept. That authority not only contributed to physicians’ ability to attract patients and thereby to increase their earnings and political power, but also to a legacy of patients’ deference to doctors. It may well have contributed also to today’s claims by some medical workers that they have the right to refuse reproductive-health services they disapprove of.

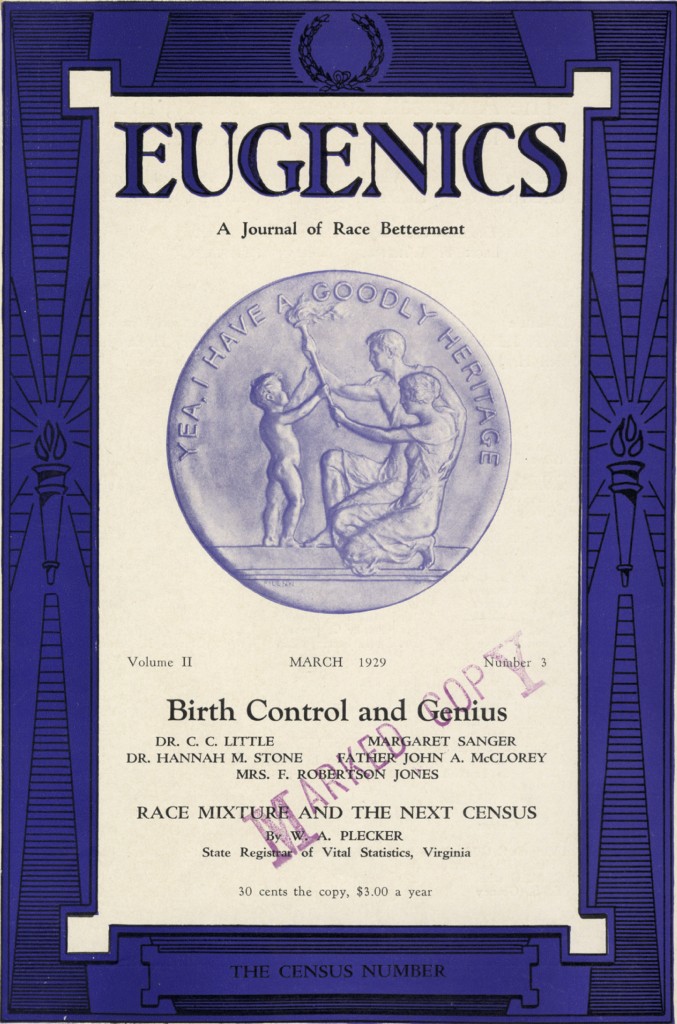

Compromise #3: 1920s birth-control advocates occasionally made common cause with eugenists, an alliance that before long proved extremely deleterious. Eugenics, the “science” of human breeding, arose in the 19th century; it promised to improve the quality of humanity by weeding out the “inferior” and encouraging reproduction among the “superior.” It became widely accepted and taught as a science in many colleges and universities in the 1920s. Eugenic “science” rested on a faulty genetics that attributed all sort of acquired characteristics—knowledge, morality, law-abidingness—to genetic inheritance. On this basis eugenists pushed contraception for the “inferior” while encouraging the “superior” to reproduce as much as possible. Worse, they convinced states to initiate forcible sterilization of the “feebleminded,” the “depraved,” the “degenerate,” the criminal.

Unsurprisingly those who were “diagnosed” into these categories were disproportionately the poor and people of color. Eugenic racism evoked an understandable suspicion of the birth-control cause on the part of many people of color, notably African Americans and American Indians, who began to fear birth control as a policy aiming to reduce their numbers. Some went so far as to call birth control a genocidal plot. Almost all progressive civil rights leaders, from W E B Du Bois to Martin Luther King Jr., and black women’s organizations supported birth control, but the fear continued nevertheless, and was promoted by many ministers with extremely conservative gender ideologies. (Today the Christian Right hypocritically appeals to these fears with anti-abortion billboards showing babies or tots with the words, “The most dangerous place for an African American baby is in the womb.” In Latina/o neighborhoods the signs read, “El lugar mas peligroso para un latino es el vientre de su madre.”)

The Griswold decision can be said to have ended one era of agitation for birth control, by holding that states could not bar married couples from access to contraception, on the basis of a right to privacy in their sexual and reproductive lives. But like many such decisions, it merely codified as fully legal what the majority had been doing for several decades. Contraceptive use was already widespread. So in a sense, Griswold was too late to be a major achievement.

Moreover, the limits to contraception’s spread were created not by law but by poverty, racism, and inequality, and Griswold did nothing to make it easier for poor Mississippi sharecroppers or West Virginia back-country people or California migrant farmworkers to access contraception.

By 1965 when Griswold was decided, a new women’s movement was simmering within the civil rights movement, and it was to renew the early spirit of Sanger and The Woman Rebel. By 1968 feminists began calling for ending the sexual double standard and decriminalizing abortion. This included, of course, recognizing the sexual rights of unmarried people, which in turn influenced the gay rights movement. When the Roe decision arrived in 1973, it seemed that the issue was settled and that the separation of contraception from abortion had ended.

But these second-wave feminists (including myself) did not realize how radically their movement had changed the meaning of reproduction control. It increasingly became seen as a part of a feminist agenda that included all sorts of demands threatening to conservatives—many of them a return to Sanger’s original platform: an end to the sexual double standard, a push for women to enter politics and the public sphere, equal wages and equal access to all jobs, equality in education and athletics, forthright sex education, and many more. True, the anti-abortion campaign was heavily funded and promoted by Republican Party strategists and donors as a way of bringing “family values” voters to quit voting Democratic. But the campaign has been successful also because it has tapped into deep-seated anxieties about society and family without women’s chastity and devotion to husband and children.

So I find myself wondering about the paths not taken. The early-20th-century compromises in the struggle for birth control may well have been essential to its progress. But they have created giant obstacles to enabling reproduction control for everyone, and we may have to struggle to overcome them for many more years.

Linda Gordon is University Professor of Humanities and History at New York University. For the first part of her career, she wrote about the historical roots of social policy debates in the US, publishing three prize-winning books in a row: The Moral Property of Women: The History of Birth Control Politics in America; Heroes of Their Own Lives, about family violence; and Pitied But Not Entitled: Single Mothers and the History of Welfare. The Great Arizona Orphan Abduction, about a vigilante action against Mexican-Americans, won the Bancroft prize for best book in US history. Her biography of photographer Dorothea Lange also won that prize, making her one of three authors ever to win it twice. Her most recent book is the co-authored Feminism Unfinished.

To commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of the 1965 Griswold v. Connecticut decision, Notches is excited to publish a three-part series that reflects upon the antecedents and legacies of this Supreme Court decision, which established that a state’s ban on the use of contraceptives violated the right to marital privacy. Our contributors, Linda Gordon, Beth Bailey and Heather Munro Prescott, invite us to reconsider the significance of Griswold. Each article suggests new ways of contextualizing Griswold and the history of reproductive politics in the United States.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com

Reblogged this on Knitting Clio and commented:

The first in a series on the legacy of Griswold v. Connecticut