Interview by Pat Omoregie

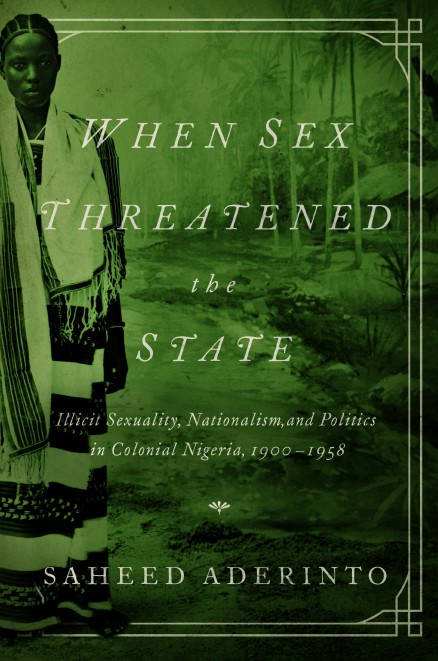

Saheed Aderinto’s When Sex Threatened the State: Illicit Sexuality, Nationalism, and Politics in Colonial Nigeria, 1900-1958 (Illinois, 2015), explores tensions in colonial Nigeria through the lens of a struggle over how to control and regulate prostitution. Aderinto argues that the British perceived prostitution as evidence of African “primitiveness,” and used this perception to help justify their “civilizing mission” in West Africa. Using European and Nigerian archives and oral histories, Aderinto traces the fault lines in colonial Nigeria between the British colonizers and diverse groups of Nigerian colonized to illustrate how the debates over prostitution challenged both African and European conceptions of politics, sexuality, and society. The first comprehensive history of sexuality of colonial Nigeria, Aderinto’s book is an invaluable addition to both historiographies of colonial Africa and African sexualities.

Pat Omoregie: How did you become interested in the history of sexuality? What motivated you to write When Sex Threatened the State?

Saheed Aderinto: A number of interrelated factors—my early exposure to archival research, the political situation in Nigeria in the early 2000s, and the need to carve a niche for myself in Nigerian historical scholarship—all contributed in motivating me to venture into the history of sexuality. In 2001, as a sophomore at the University of Ibadan in Nigeria, I was fortunate to work as research assistant with Dr. Laurent Fourchard, the Director of the Nigerian Office of the French Institute for Research in Africa (IFRA). Fourchard is an urban historian, interested in the social aspect of colonial African cities, among other interesting themes. He asked me to help him collect archival materials on the history of juvenile delinquency from the Ibadan Office of the Nigerian National Archives, which, fortunately, is located on the campus of the University of Ibadan. Consistent reference to prostitution in archival materials on juvenile delinquency pulled me into the secret lives of men and women who bought and sold sexual favor in the past, and to the study of the city where transactional sex took place.

Coincidentally, the early 2000s marked a turning point in the post-colonial Nigerian history of prostitution. The government of Olusegun Obasanjo (1999-2007), because of domestic and international pressure, began a well-publicized repatriation of Nigerian women working as prostitutes in Europe, among other parts of the world. The government went on to pass the Trafficking in Persons (Prohibition) Law Enforcement and Administration Act, the most comprehensive law on prostitution and human trafficking since Nigeria’s independence from Britain in 1960, and established an institution (the National Agency for the Prohibition of Traffic in Persons) to police girl-child sexual exploitation. In addition, new NGOs claiming to help rehabilitate prostitutes emerged all over the country in an unprecedented manner. One of the numerous public rhetoric about prostitution in the early 2000s was that it was “unAfrican” and a “new” phenomenon caused by the Structural Adjustment Program, an austere IMF economic policy that destroyed the Nigerian economy from the mid-1980s. You can imagine reading stories about prostitution in colonial archives and newspapers in the 1920s, amidst a protracted public debate about the “un-Africaness” and “newness” of sex work in 2001. It was mind blowing. After completing my undergraduate education at the University of Ibadan in 2004, I enrolled at the University of Texas at Austin in 2005 to do a PhD work on the history of sexuality. When Sex Threatened the State, is the revised version of my doctoral thesis successfully defended in spring of 2010.

PO: Can you tell us what you mean by the phrase, “When Sex Threatened the State”?

SA: Between 1900 and the 1960, diverse groups of Nigerians and British colonialists were concerned that certain expressions of sexuality threatened their understanding of proper use of the body, time, and leisure. The assumption was that prostitutes were the purveyors of venereal diseases (VD) such as gonorrhea and syphilis. Moralists also thought that prostitution was fueling a subculture of criminality and juvenile delinquency. Sexual immorality was defined in a manner that aligned with the ideology and consciousness of a spectrum of people who believed that sex outside marriage, public vulgarity and obscenity, as well as multiple sexual liaisons should be regulated/prohibited in the interest of public good. For the British colonial officers, VD constituted a security problem, because its incidence was high among the military—the so-called guardian of the empire. They also thought that crime perpetuated by delinquent juveniles and criminals, who served as touts and procurers in the subculture of prostitution, was capable of undermining the smooth running of the colonial state, or even bringing it down.

So, private vice reverberated into the public space, creating a host of interrelated “problems,” all of which moralists believed must be dealt with. Prostitution regulation also tied directly to the idea of “civilization,” the biggest project of the British in Nigeria, as elsewhere in Africa. Prostitution, among other forms of “dissident” sexual and social expressions, was codified as a sign and symptom of African distinctive sexual aberration, which colonialism was expected to correct through its civilizing mission. By treating prostitution as a “distinctive” African problem, colonial administrators created an Africanized vocabulary of sexual otherness for a “problem” that transcended racial, ethnic, and geographical boundaries. African sexual norms were evaluated through a racial prism, not by the prevailing socio-economic circumstances which made prostitution an inevitable component of daily life in the colonial city.

The notion that prostitution intensified the spread of VD was not unique to Nigeria or any part of colonial Africa. What seems unique to Africa’s most populous country was the involvement of highly educated African men and women in the debate over sexuality regulation. For me, the ability to present a Nigerian-centered narrative of sexual aberration expands the scope of investigation into sexuality history, since most of the existing works tend to focus on the activities and the ideas of the colonialists. I consider the articulation of Nigerian perspective as one of the most significant contributions of When Sex Threatened the State to African sexuality history.

Nigeria is a unique country, even though it shares a lot of commonalities with several other African countries. During the colonial era, it boasted of a vibrant group of highly educated men and women (which was rare in most parts of Africa). These individuals and groups voiced their opinions about the impact of sexuality in their “modernizing” world, leaning on a host of conflicting and often irreconcilable binaries such as colonial “progress and failure,” “normal and abnormal,” and “tradition and modernity.” Hence, two types of states existed during the period covered in my book: one was the colonial state under the imperial government of Britain, the other was the “imagined” state, which the African educated elites wanted to inherit after the projected demise of colonial rule.

Of equal importance is that my book presents the most complex narratives, to date, about the connection between nationalism and sexuality in Africa. Nigerians, especially the politicians and professionals did sexualize nationalism. To sexualize nationalism is to see the elements of sexuality in the agitation against colonial domination and fight for political self-determination. One of the missing treads in African sexuality history is the limited attention given to how sexuality intersects with nationalism. Before and after the WWII, the anti-colonial movement was structured partly around the need to selectively appropriate elements of African culture that were “progressive” while doing away with the “retrogressive” ones. This selective appropriation of modernity was reflected in several spheres of the people’s engagement with colonialism. Indeed, much of what Africans fought against was the failure of the colonial masters to deliver its professed promise to “civilize” the colonies through adequate provision of modern infrastructure. What my book did is to locate sexuality discourse within the broader framework of nationalism, selective modernity, and agitation for a civilized society—the imagination of many educated elites and the British colonizers.

PO: Your book challenges historians to redefine existing methodologies. What do you mean by “A ‘total’ history of sexuality?” Why should historians follow this methodology?

SA: The idea of a “total” history of sexuality challenges historians to develop encompassing paradigms for studying the sexual lives of the people of the past. I am aware of the fact that the whole notion of a “total” history is problematic, partly because historians don’t and can’t know everything that happened in the past. Yet, we must seek to understand the past to the fullest possible length, and within the limitation placed by time, resources, and data. Anyone familiar with the literature on African sexuality knows that existing works tend to be compartmentalized, that is examined from a specific and often narrow dimension. So, we have seen the proliferation of works using race, gender, and class to study prostitution. Others have looked at prostitution from labor, social justice, and public health perspectives. For me, the story of prostitution must be researched from a much wider perspective, bringing in several subfields in an attempt to “fully” comprehend how people in the past experienced love and loving. I therefore call for a paradigm that doesn’t “over-compartmentalize” African sexuality history—an approach that pulls from medical, social, cultural, political, economic, urban, ethnic, and childhood history, among other subfields of history, to shed light on the complex subject of sex.

I’m not downplaying the importance of race, class, and gender in unearthing events of the past—as my book clearly shows, these axes are inevitable. I just think that we historians should be doing more to broaden the scope of our investigation. I think that we don’t know as much as we should about the private existence of the makers of the African past. The ways in which historical works are structured must also be informed by the circumstances unique to each location. So, When Sex Threatened the State is grounded in the historical reality peculiar to Nigeria, while also challenging historians of other countries and colonial locations to rethink over-flocked models. I discovered, as I was writing the book, that the story of prostitution in Nigeria deserves an approach that is broader than what we see in most present studies. In addition, I wanted to write a book that speaks to the reality of our time, within the limits of available sources. Today, the war on prostitution and sexual exploitation of minors is an active and serious one in several countries in the world. To write about the history of colonial prostitution is to attempt to correct the popular notion that the Nigerian past was a “morally disciplined” one, as professed by some moralists. Beyond helping to move the frontier of knowledge forward, my book has also allowed me to place contemporary issues in proper historical perspective and contribute to the ongoing debate about the value of historical knowledge in the volatile discourse of development in Nigeria.

PO: One of the main issues you engaged in your book is the “Idea of an Erotic Child.” What do you mean by this term? What role did colonial ideas of childhood play in shaping the politics of sexuality?

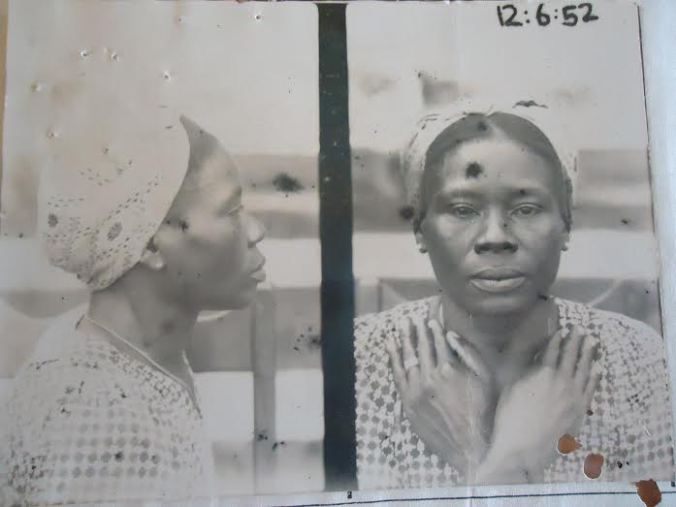

SA: The “idea of an erotic child” is the second most important aspect of my book. If you take a quick glance at existing works on the history of prostitution in colonial Africa, you’ll discover that scholars have completely overlooked the importance of age in understanding the sexual lives of men and women of the past. When Africanist historians write about colonial prostitution, they don’t acknowledge it as an age specific profession. Yet, the complex definition of a “child” and an “adult” shaped the tenor of sexual politics in a very profound manner. My archival materials, oral interviews, newspapers, and court records explicitly demonstrate that colonial Nigerian society did not think that adult and child prostitution posed the same level of threat to prevailing notions of sexual respectability. Rather, the dynamics of child and adult sexualities were sometimes constructed to reflect the perceived relationship between age and sexual criminality.

From the 1920s, educated elite women in Lagos, began to see minors as individuals who needed state protection/paternalism because cultural and economic practices like betrothal and street vending/hawking exposed them to sexual danger. These women (Oyinkan Abayomi and Charlotte Obasa, among others), working through their associations, laid the foundation of the 21st century agitation for the girl-child’s welfare. They were the trail-blazers in women’s activism. For elite women, underage girls were objects of sexual pleasure, being exploited by men and women.

Of course, the colonial government was also convinced that underage girls were sexually exploited; its solution to the problem did not align with that of elite African women. So, what I tried to do is to challenge historians to think more broadly about the evolution of the war against sexual exploitation in historical terms. Unknown to many of us, the language of sexual degeneration was one of the visible manifestations of the “problem” of colonial modernity.

My book is the first to really tackle the social and legal construction of childhood in relation to the war against underage prostitution in Africa. In two separate chapters, I put to test, how social and legal meanings of childhood were contested in diverse domains—in correspondence among colonial officers and Africans, in the town hall meetings, on the pages of the newspapers, and in the court of law. My discovery is fascinating. Although legal statues on child prostitution mirrored the realities of the colonial society, they were compelled to yield to the social construction which was in agreement with everyday life. Hence, the social interpretation of sexual deviance, that is how the community or people viewed underage sex won, in the legal tussle to determine criminal liability for girl-child sexual exploitation.

PO: What kind of sources did you use? And how did you conduct oral interviews about a difficult subject like sexuality?

SA: I combed the three main branches of the Nigerian National Archives at Ibadan, Enugu, and Kaduna for archival materials. As my bibliography clearly shows, I used a lot of published primary sources, which include laws and legislative debates, and newspapers published between 1900s and 1950s. Indeed, newspapers really helped me to unearth the Nigerian voice and situate my narratives within the broader theme of anticolonial sentiment and nationalism. Oral history of Lagos is really quite interesting. The technique I used in collecting my oral history reflects my agenda, which is to locate prostitution within the broader socio-economic, cultural, and political life of the city. So, I basically asked my respondents to tell me everything they knew about everyday life in colonial Lagos—the kinds of dress people wore; the most popular music they listened to; how they spent their free time or socialized; sex and sexual networking; and the conditions that shaped everyday engagement among diverse groups of people. I asked big questions about their identity as colonial subjects in relation to gender, ethnicity, and social class.

PO: You have been praised for helping to pioneer Nigerian history of sexuality with your book, the first book-length study of sexuality in Nigeria, and numerous articles. What is the future of Nigerian history of sexuality? Which areas of the field do you think historians should focus on and why?

SA: The opportunities to expand the histories of Nigerian sexualities are limitless. Although, my findings have a nation-wide implication, much of my data comes from Lagos, the colonial capital. I’m sure that works on other colonial cities would help expand the historiography of Nigerian sexualities. That’s why I’m happy that your doctoral thesis is focusing on Benin City and transnational prostitution. I look forward to reading it. What is more, the cultural difference between northern and southern Nigeria should yield some interesting insights. If religion shaped the contour of sexual politics in colonial northern Nigeria, in the south the debate was mostly secular. So, a comparative history of prostitution, that acknowledges religious and cultural difference, would complement existing works. Although a number of anthropological works exist, I’m more disposed to studies that place sexuality in historical perspective.

In addition, much of the existing works focus on the colonial period. There is a dearth of precolonial and postcolonial history of sexuality. Histories of precolonial and postcolonial sexualities must devise creative methods of harvesting and interpreting materials. Future studies on the precolonial era would have to rely on oral tradition, which like all other genre of sources pose a number of limitations. The absence of official documents on postcolonial period (due to the refusal of Nigeria to declassify documents produced after 1960) would compel historians to depend almost exclusively on oral history, newspaper, and other categories of written documents in the public domain. Be that as it may, the frontier of knowledge must be expanded. We must continue to seek creative ways to study Nigerian sexualities, against all odds.

One of the major criticisms of the current literature on Nigerian sexuality history is its overwhelming focus on heterosexual affairs. Our knowledge of same-sex affairs in precolonial and colonial periods is very limited. Research on African homosexualities would help correct the obnoxious notion that same sex affairs is “un-African” and a Western European import. But more importantly, it would unveil the complexity and diversity of Nigerian sexual lives and expand the horizon of knowledge.

Saheed Aderinto teaches at Western Carolina University. He is the author of When Sex Threatened the State: Illicit Sexuality, Nationalism, and Politics in Colonial Nigeria, 1900-1958 (University of Illinois Press, 2015), among other books.

Pat Omoregie teaches history at the University of Benin, Nigeria. She is also a doctoral student at the University of Ibadan where she is completing her thesis on the history of Benin women and international prostitution.

Pat Omoregie teaches history at the University of Benin, Nigeria. She is also a doctoral student at the University of Ibadan where she is completing her thesis on the history of Benin women and international prostitution.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com