Alana Harris and Timothy Willem Jones

In the first week of July, we were among over two hundred historians who attended the Rethinking Modern British Studies conference at the University of Birmingham. Alongside our own panel on religion and sexuality, a number of the plenary speakers and the concurrent sessions drew upon a ‘history of emotions’ methodology to chart what Stephen Brooke described as the ‘affective ecologies’ operational within our diverse research agendas. Lucy Robinson, in her excellent blog on the conference, urged historians of modern Britain to ‘follow the feels’ because a history of affect, rightly contextualised, allows for the interrogation of materiality and the political – if you ‘trace the affective ecologies, you also follow the money [and] map the power’. As Will Pooley rightly reflected in his post ‘Emotions go mainstream’, there is a distinction to be drawn between a ‘history of emotions’ methodology, which unpacks the historically contingent framings and freightings of emotions, and ‘emotional histories’, or ‘histories with emotions in’. And yet, as Rhodri Hayward argued, there remains a definitional and conceptual ambiguity to the ‘affective turn’, which perhaps explains its present-day fecundity. Such reflections echo many of the questions we considered in compiling our recent edited collection, Love and Romance in Britain, 1918-1970. Our book argues that love has a history, but that its history is not quite what we thought it was. A closer look at changes in love, relationships and affection between 1918 and 1970 raises questions as to whether love ever had a golden age.

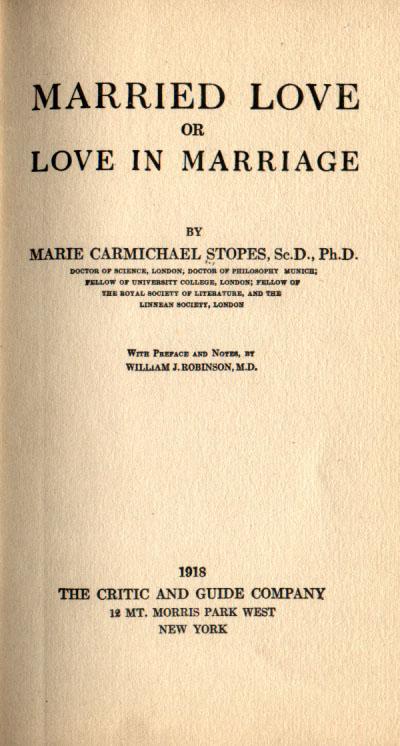

In 1918 Marie Stopes, then a pioneering female palaeobotanist, published a book that would transform her life and many others. Married Love was a popular marriage guide and sex manual that advocated for marriages grounded in mutual affection, and expressed in mutual sexual pleasure; it aimed to combat sexual ignorance in marrying couples. In particular, it propounded theories about female sexual desire – women’s ‘primitive sex tides’ – which Stopes argued couples needed to understand in order to achieve ‘union with another soul, and the perfecting of oneself which such union brings’.

The book was a runaway success, being continually reprinted, and launching Stopes’ new career as a sexologist and birth control advocate. Thousands of women and men wrote to Stopes after its publication asking for advice. As Hera Cook argues, it is difficult to overestimate the innovativeness and the importance of Stopes’ work in starting and shaping the discourse on heterosexual marriage, sex and love in 1920s Britain. It was explicit (for its time), popular and spoke to ordinary people’s anxieties about love, sex and marriage. It was also intensely romantic. In its emphasis on mutuality, it was self-consciously both feminist and modern.

Fifty years later, another sex manual was published, which reflected an equally seismic shift in sexual and affective culture. British gerontologist Alex Comfort’s The Joy of Sex: A Gourmet Guide to Lovemaking (1972) was also written to combat ‘the mischief caused by guilt, misinformation and lack of information.’ Unlike Stopes’ frank, but demur text, Comfort’s book was graphically illustrated. It celebrated sexual pleasure as an end in itself, just like eating. Modelled on the best-selling Joy of Cooking, it set out a comprehensive sexual menu for lovers to explore, including everything from masturbation to sadomasochism.

For Comfort, sex and love could be separated. Sex need no longer be contained within the bounds of ‘lifelong monogamy’; it could simply be a ‘rewarding form of play’. Published at the same time as women’s liberation was emerging, his message was received by a public prepared for permissiveness by recent access to the contraceptive pill (1963), the legalisation of abortion and homosexuality (1967) and the liberalisation of divorce (1969). The Joy of Sex sold over 12 million copies worldwide. Its place on family bookshelves and under coffee tables both marked and contributed to the popularisation of the sexual revolution.

For many, the sexual revolution also marked the end of ‘modern love’. Marcus Collins argues that it ‘at once realized and rendered obsolete mutualist dreams of sexual harmony’, while Dora Russell observed that the sixties had spawned ‘a very great deal more sex … [but a] decrease in the volume of love’.

Our recent book revisits this period between Modern Love and The Joy of Sex – love’s apparent ‘golden age’. It provides a critique of the often taken for granted chronologies of emotional modernity, interrogating a historiography climaxing in an emotional and moral interlude in the 1960s. Rather than privileging the 1960s as an apex and turning point, our book fleshes out a gradual, non-linear narrative that reveals the significance of longer-term ideological and cultural trends, as well as the impact of cataclysmic events such as the First and Second World Wars or the abdication crisis.

The five decades between the First World War and women’s liberation saw profound changes in understandings, expectations and usages of love and romance. In 1918 Marie Stopes prophesied the dawning of a new era of mutual love, in which heterosexual couples would be awakened to ‘a new and unprecedented creation … the super-physical entity created by the perfect union in love of man and woman’. Her vision of modern Married Love became widely idealized in novels, psychology, the state-sponsored (and Catholic) marriage guidance movement and even in the Church of England’s marriage service.

As the contributors to our book show, however, this distinctive nexus of sex, love and romance had always only been an ideal. Although romance leading to love expressed in mutual companionate marriage may have become the collective emotional standard for much of British society by the 1950s, it was clearly not universally adopted by all of Britain’s emotional communities. The gradual distancing of love, sex and marriage in popular expectation from the 1960s, a dislocation emblematized by Alex Comfort’s Joy of Sex, was thus not the end of a golden age in which Stopes’ vision had materialized. It was a collective recognition that the emotional ideals of the previous two generations had rarely been realized.

Alana Harris is a historian of gender, religion and migration and teaches at King’s College London. She is currently working on a new book that examines English Catholics’ shifting discourses and experiences of love, marriage, sexual knowledge and contraceptive practices, especially the pivotal debates about the Humanae Vitae encyclical (1968). She tweets @DrAlanaGHarris

Alana Harris is a historian of gender, religion and migration and teaches at King’s College London. She is currently working on a new book that examines English Catholics’ shifting discourses and experiences of love, marriage, sexual knowledge and contraceptive practices, especially the pivotal debates about the Humanae Vitae encyclical (1968). She tweets @DrAlanaGHarris

Timothy Willem Jones is a cultural historian of sexuality and religion. He is lecturer in history at the University of South Wales and ARC DECRA research fellow at La Trobe University. His recent work includes Sexual Politics in the Church of England, 1857-1957 (Oxford, 2013), Love and Romance in Britain, 1918-1970 (Palgrave Macmillan, 2015) edited with Alana Harris and Material Religion in Modern Britain: The Spirit of Things (Palgrave Macmillan, 2015) edited with Lucinda Matthews-Jones.

Timothy Willem Jones is a cultural historian of sexuality and religion. He is lecturer in history at the University of South Wales and ARC DECRA research fellow at La Trobe University. His recent work includes Sexual Politics in the Church of England, 1857-1957 (Oxford, 2013), Love and Romance in Britain, 1918-1970 (Palgrave Macmillan, 2015) edited with Alana Harris and Material Religion in Modern Britain: The Spirit of Things (Palgrave Macmillan, 2015) edited with Lucinda Matthews-Jones.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com

Great post: I look forward to seeing the book!

I can’t take credit for the important history of emotions vs history with emotions distinction, though. Someone in the emotions panel suggested this in the discussion afterwards. If anyone from the conference knows who this was I’d be glad to know…