If any field of history provoked more dismissive reactions from the old guard at its emergence than the history of sexuality, it was the history of food. Food historians routinely begin historiographies by reviewing the insults they received from mentors and peers at the outset. Rebecca L. Spang, author of the multiple-prize-winning The Invention of the Restaurant, recalls that when she first expressed an interest in food history during her sophomore year of college, she was told “Miss Spang, this is Harvard. You can’t do Home Ec.”

1/2 To think that when I first expressed interest in food history, I was told, "Miss Spang, this is Harvard. You can't do Home Ec."

— Rebecca L. Spang (@RebeccaSpang) August 11, 2015

Times have changed. No less worthy an authority than the American Historical Association has recently sanctified the field by endorsing a Companion Guide on the theme of Food History (the coeditors of the volume are professors at Harvard, Yale, and University of the Pacific). As the reviewer for Choice Magazine put it, “Any remaining doubts about the legitimacy of food history are put to rest by this edited volume.”

Despite this new veneer of acceptance, expressing interest in both the history of food and the history of sexuality still has the power to raise eyebrows. If a historian wishes to work on the history of food, she should at least have the good taste to attach it to a more reputable field such as politics or class. A research project can barely hold up under association with two morally suspect fields. I almost feel the need to apologize when I tell people what I’m working on these days, which is why I’ve been so delighted to edit this series of essays on the history of food and sex for Notches. Several recent wonderful essays had sparked my sense that there is a community of interest in the intersections of the history of food and sexuality. I proposed the series as means to broaden this community of shared interests. The submissions expanded my sense of community far beyond what I could have expected.

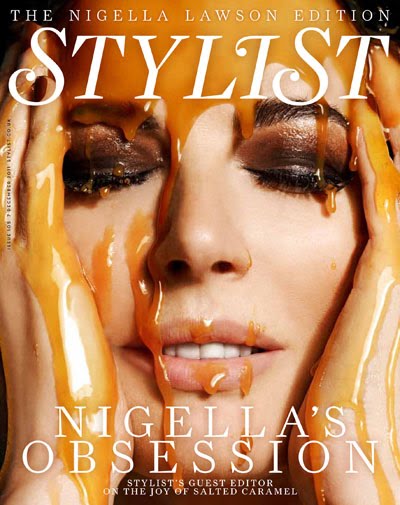

In these essays, you will find scholarship that gives depth and context to the routine linkages made between food and sex in contemporary culture, for example in the concept of “food porn.” The term food porn is used to describe hyper-exaggerated visual images of food designed to stimulate appetites which, ironically, the images cannot satisfy. In the food porn aesthetic, as journalist Cari Romm points out in her recent Atlantic article, the glossier, the gooier, and the stickier, the better.

On the flip side, marketing campaigns depict female food celebrities like Nigella Lawson and Padma Lakshmi as consumable objects, on par with the foods they prepare. Advertisements show them stuffed into body-hugging angora sweaters and satiny dresses, like Vienna sausages wrapped in Pillsbury biscuit dough to make pigs in a blanket.

The essays in this series provide us with the critical tools to examine the conjunctions of food and sexuality that extend beyond popular depictions linking fast food and women’s bodies as tasty commodities in the capitalist marketplace. The series extends in time and place from pre-Hispanic Mexico, through turn-of-the-century Finland, to mid-twentieth century Wisconsin. The authors examine the conjunction of food and sex in myth, language, religion, literature, and the home, as well as in the marketplace. And finally, they identify a wide range of emotional dynamics linking food and sex, encompassing not only pleasure, but also revulsion, nostalgia, and fear.

A note on pleasure and fear: As Carole Vance famously asserted in her 1984 collection, Pleasure and Danger, sexuality provokes ambivalent yet extreme responses. This argument is echoed by sociologist Priscilla Parkhurst Ferguson’s 2014 work Word of Mouth, which observes that a similar ambivalence haunts humanity’s relationship to food, since any delicious forkful might put our lives in danger. The essays in this series don’t shy from these poles; they launch courageous expeditions into both negative and positive feelings.

Considering that sexuality and food can be two of life’s greatest enjoyments, it is striking how rarely the historiography of either subject prioritizes the discussion of pleasure. For historians worried that their interests in sexuality or food appear prurient, discussions of pleasure can be taboo. Yet the subject of pleasure demands attention when discussing how food and sex have been linked. As the contributors reveal, historic constructions of the pleasures of food and sex are both ubiquitous and diverse, exceeding the familiar heteronormative equation of slim young women’s bodies with indulgent foods. Women are the subjects, not the objects, of lust in Gustavo Corral’s discussion of a Toltec myth that describes a woman’s desire for a deity’s penis. Christopher Hommerding turns heteronormativity on its head with his description of the pleasure that customers took in the queer performance of two gay men who ran a mid-century Midwestern restaurant. And the conventional hierarchy of pleasures comes into question in Laika Nevalainen’s account of the longing that Finnish “summer widowers,” left alone to work in the city while their families vacationed, felt for their wives’ cooking.

For all its pleasures, food’s perils provoke just as much attention. Indeed, the essays in this series reveal that the histories of food and sexuality often meet at the nexus of fear. Sexual fears of interracial promiscuity intersected with concerns about adulterated or corrupted food in critiques of early nineteenth-century urban hucksters, according to Robert J. Gamble. Benjamin Carp traces overlapping anxieties about sexual promiscuity and food a century earlier, to Anglo-American suspicions of tea consumption. Readers might be surprised to discover that such critiques were not limited to conventional attacks on women’s tastes for luxuries, but extended to assertions that drinking tea lured men into sodomy. The illogicality of this claim compels investigation into the historical circumstances that produced it, uncovering the ways in which food and sex have been sites that constituted social norms while defining deviance. Thus Scott Larson argues that founding father Benjamin Franklin treated both food and sex as central ways to manage bodily desires and create disciplined citizens. The opposite of that proposition, as I have discovered in my own research, is that nineteenth and twentieth-century queer figures often embraced gourmandism as a way to signal their transgressive sexual behaviors and desires.

In sum, this series reveals that ideas about food and sex are often about more than food and sex. Both possess tremendous symbolic power, which stems from their integrality to the human experience and the strength of the reactions they evoke. As seen in the series, these symbolic powers make food and sex excellent windows onto core topics of interest to historians, such as colonization, empire, gender, politics, class, and race. At the same time, these essays demonstrate that food and sex should be regarded themselves as core topics of interest, worthy of study in their own right, not as semiotic ciphers, but as universal elements of the historic human experience. How many more times and places might historians visit to observe the conjunctions between food and sex? I look forward to reading the results of their researches.

I now invite you to read the first article in our six part series, Tempests and Teapots: Sexual Politics and Tea-Drinking in the Early Modern World by Benjamin L. Carp. Bon Appétit!

Rachel Hope Cleves is professor of history at the University of Victoria in British Columbia. She specializes in early American history and has written about the history of same-sex marriage and about American reactions to the French Revolution. Her most recent book is Charity and Sylvia: A Same-Sex Marriage in Early America (Oxford University Press, 2014). You can follow her on twitter @RachelCleves.

Rachel Hope Cleves is professor of history at the University of Victoria in British Columbia. She specializes in early American history and has written about the history of same-sex marriage and about American reactions to the French Revolution. Her most recent book is Charity and Sylvia: A Same-Sex Marriage in Early America (Oxford University Press, 2014). You can follow her on twitter @RachelCleves.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com

Your research is fascinating. Do things change over time, or does time keep marching on while things change at a much slower pace? I wonder how many marriages would be better off if each spouse got a three week break. IN the 10 weeks of vacation everyone should have, four spent as a family, and then three with just Dad and the kids at home and three with just mom and the kids at home. I know somewhere in Europe this exact scheme is in place for those with a lucky enough life to make it work. it seems this helps the marriage stay alive rather than hurts it. it does take some very NON-jealous spouses though.